This is Mike’s Shiloh Sharps .45-70 that he won at the National Championships in 2006, displayed with a plaque at Shiloh Rifle Manufacturing’s 2017 invitational. The scope is a Montana Vintage Arms 6x.

In the fall of 1972, I was out of college, back in West Virginia from my annual summer foray to Yellowstone National Park. This was the first time in my life, I was getting a paycheck for more than minimum wage. With that first check, I scouted all the area’s gun stores for a Marlin Model 1895 in .45-70. When one was finally discovered, I hit the jackpot because next to it was a Harrington & Richardson replica of the .45-70 Model 1873 “trapdoor” Springfield carbine. I bought both guns and 100 rounds of Remington factory loads with 405-grain JSP bullets.

The U.S. Army adopted these Model 1873s along with the new .45 Government round: a cavalry carbine (top) and an infantry rifle (bottom).

While shooting the factory loads, in order to gain handloading brass, I ordered the following from Lyman: reloading dies, a shellholder, a .457-inch lube/sizing die, a top punch No. 374 and a bullet mould 457124 for a 385-grain RN bullet. (Except for that first mould, I still use those reloading items.) Originally named .45 Gov’t, civilians quickly gave it the .45-70 moniker due to its original powder charge weight, although a special carbine load soon appeared with only 55-grain charge. Case length was 2.10 inches. The first government bullets were 405 grains for both powder charges, but in the 1880s a 500-grain bullet was introduced. All were swaged roundnoses.

Elmer Keith wrote that his load for Winchester Model 1886s was a hefty charge of IMR-3031 with (I think) 405-grain JSPs. These new Marlins were touted as “strong” so I reduced Elmer’s load by one grain, figuring that would be safe with my lighter 385 grain bullet. Then a Weaver 4X scope was mounted, but no thought was given to proper eye relief.

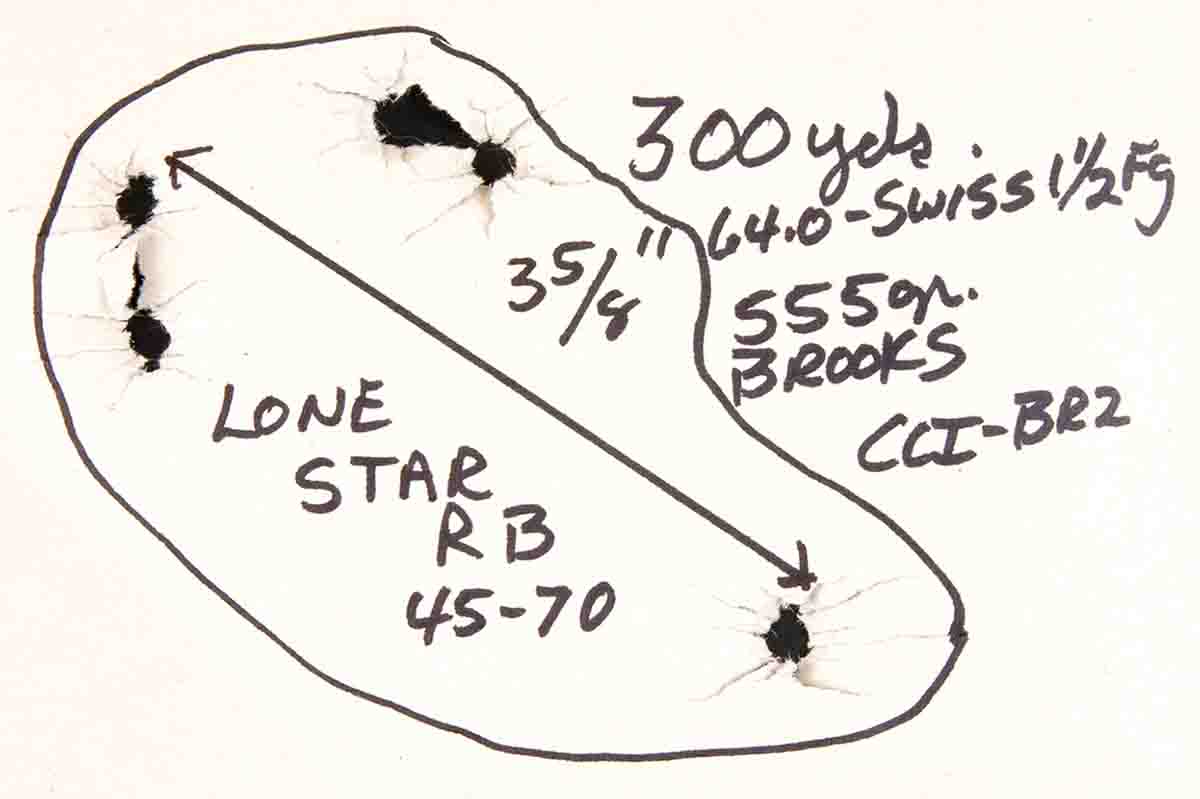

One of Mike’s very accurate .45-70 competition rifles was this Lone Star No. 1 rolling block. The barrel length is 32 inches.

So armed, I went to my shooting spot with a friend to give my “hot” .45-70 handloads a try. They were almost my last! With the Marlin’s first shot, I was blinded by blood and asked my compatriot to grab the rifle while I wiped it from my eyes. That was my first and only scope cut. Seeing that I wasn’t seriously injured, he laughed about the huge lump on my forehead but then pointed to blood flowing through my shirt. Recoil had split the skin on my shoulder. I came close to swearing off .45-70s forever.

This is Mike’s Model 1873 trapdoor Springfield, which he used in 2016 to make his best single .45-70 shot.

The upshot was, I didn’t give up .45-70 handloading, but decided that trying to make a century-old cartridge into a modern magnum was bad business. Factory duplication loads as listed then in Lyman’s manuals became my key to happy shooting. Hundreds of .45-70s were fired with the H&R carbine with nary a problem. To be honest, I never did truly forgive that Marlin. During the summer of 1973 it traveled with me on a long pack trip through Montana grizzly country, during which it fell off a pack horse, busting the rear sight. Back in civilization, it was sold at a discounted price. I have never missed it.

As might be deduced from the above, in those days I was quite a traveler. In 1975, now a Montana resident, I was back in West Virginia for a family visit. One spring day I found a well-stocked gun store in eastern Kentucky and was browsing even though I couldn’t buy. A fellow walked in with an original Springfield “trapdoor” Model 1873 carbine over his shoulder and offered it to sell it to the counter guy. When he declined, I asked if I might try to purchase it. With counter guy’s okay, I dickered with the gent and bought it. I still have it, but for financial reasons, the H&R carbine had to go. It is missed.

Instead of detailing the several scores of .45-70 rifles and carbines I’ve either owned or borrowed for articles, allow me to condense as follows. There have been dozens of Sharps Model 1874s, originals and replicas made in Montana and Italy. Passing through my hands have been several original Winchester Model 1886 leverguns and Japanese replicas, a couple of original Winchester high walls, one Peabody replica, several Springfield Model 1873/1884 “trapdoor” infantry rifles, including a Pedersoli replica and one Marlin Model 1881. I had built a custom rifle based on an original Remington rolling block action, and bought one replica rolling block from the now defunct Lone Star Rifle Company. Most recently I’ve written about the new Shiloh Rifle Manufacturing Model 1877.

These .45-70s have ranged from 20-inch barreled Model 1886 carbines to 34-inch barreled single shots. They have worn open sights, target peep sights and scopes. Beginning in 1986, .45-70 became my primary choice for Black Powder Cartridge Rifle (BPCR) Silhouette. With .45-70s alone, I’ve shot more than 100 BPCR silhouette matches along with some 800, 900 and 1,000-yard paper target matches. My wins haven’t been numerous, but did include the 2008 Arizona State Championship for Scoped BPCR Silhouette. My rifle then was a Shiloh Model 1874 .45-70. I won that particular .45-70 two years earlier at the National Championships by being high iron-sight shooter using a Shiloh rifle.

Mike has also had several vintage and replica Model 1886 .45-70 leverguns. This one was made by Miroku of Japan, imported by Browning and bears the Winchester trademark.

In hunting, I’ve shot deer, elk and bison with .45-70s. In the late 1990s in Texas, I participated in a whitetail depredation hunt, but didn’t keep track of how many I shot personally, except they were all with one Shiloh Sharps. We’ll return to that later.

In regard to handloads, I’ve assembled well over 10,000 .45-70s. Those loads have carried only a few hundred jacketed bullets weighing from 300 to 400 grains. The cast bullet handloads have ranged from 290 to 560 grains. The former were used in the H&R carbine for plinking and the very heavy ones were used in BPCR silhouette and paper target competition. Among the more than 50 bullet moulds I’ve owned for .45-caliber rifles, there have been ones for HPs, RN/FPs, Gov’t RNs, spitzers, and various Creedmoor styles. The latter are “gently” curving RNs.

A factor .45-70 shooters need be aware of is rifling twist. In 1873, Springfield’s new infantry rifles and cavalry carbines were given 1:22 twists. It seems commercial .45-70s usually had 1:20 twists. Most modern single shots used for long-range competition have 1:18 rifling twists. Very heavy cast bullets need the 18-inch twist. I now size all .45-70 cast bullets at .459 inch and use either SPG or DGL lubes.

The .45-70 Mike has written about most recently in Handloader magazine is the Shiloh Model 1877.

The cast HPs mentioned above came from Lyman mould 457122, weighing 336 grains of 1:20 tin-to-lead alloy. I learned that those bullets over 68 grains of GOEX FFg black powder were fine for small Texas whitetails. All bullets exited and the deer seldom left their tracks. However, back in Montana, I made a good broadside shot on a mule deer buck at about 75 yards but he kept going. Following up, I found him lying with his head up and finished the job. The bullet’s base, sans nose, was found under his skin on the off side.

Mike has used Montana Vintage Arms vernier tang sights for all of his .45-70 competition rifles.

After that experience, I turned to Lyman’s 457193 for hunting. That mould drops a 420-grain FN when cast of 1:20 alloy. With 65 to 70 grains of FFFg black powder under it, it’s good for most anything in the lower 48 states out to 200 yards. For smokeless-powder shooters I’d recommend the near identical RCBS 45-405-FN. With modern powders, its gas-checked base has delivered better accuracy than the plain base Lyman bullet. Both of those flatnoses are naturals for leverguns.

Speaking of propellants, aside from black powder and after much experience, I only use two smokeless types for .45-70s. Those are IMR-3031 and Accurate 5744; both of which are suitable for cast or jacketed bullets. (Vintage rifles should be deemed safe by a qualified gunsmith before firing with any propellant.) The accompanying table will show one heavier IMR-3031 load that should only be used in modern .45-70s. I helped a friend prepare it for his Montana mountain goat hunt with a Shiloh Sharps in which he was successful.

At one time, Mike owned all these .45-70 rifles and used them in NRA BPCR Silhouette and NRA Black Powder Target matches. Only the top one remains now. Top to bottom: Shiloh Model 1874 Rough Rider, Shiloh Model 1874 No.1, custom-built Remington No. 1 rolling block and C. Sharps Arms Model 1874 Long Range.

Thousands of cast bullets have been fired through my .45-70 target rifles – mostly Sharps and rolling blocks. The NRA BPCR Silhouette game requires precision. For instance, the ram silhouette is at 500 meters (547 yards) and it only measures 13 inches from belly to backbone. Many modern shooters seem incredulous and even doubtful that rifles designed 150 years ago, firing black powder, cast bullets and wearing peep sights can achieve such precision. It is true, albeit handloads must be assembled with great care.

(1) An 1880s vintage U.S. Army carbine load with 405-grain bullets, (2) Mike’s handload closely duplicating it with a 390-grain Lyman bullet No. 457124, (3) an 1880s vintage infantry rifle load with a 500-grain bullet and (4) Mike’s handload closely duplicating it with 520-grain bullet Lyman bullet No. 457125.

Here’s a funny story; friend Kirk Stovall stopped at my shooting house one afternoon when I was firing my original Sharps .45-70 using Lyman’s bullet 457125 over a forgotten charge of black powder. My 300-yard, five-shot group was less than 4 inches. Kirk sat down with his brand-new .30-378 Weatherby with a

Schmidt & Bender scope and muzzle brake. (His first shot’s muzzle blast blew my clock off the wall 14 feet behind him.) After he fired five rounds, my .45-70 group fit easily inside his .30-378 cluster. He soon sold that rifle.

Mike is shown shooting one of his Sharps Model 1874 .45-70s at a BPCR Silhouette event at the Deep Creek Range near Missoula, Montana.

Over the years I’ve written how-to articles about .45-70 black powder loading in

Handloader magazine and in my

SHOOTING BUFFALO RIFLES and SHOOTING LEVER GUNS books (available from Wolfe Publishing). I won’t delve into it here. One thing I will say: my prejudice for .45-70 competition moulds is that they must be iron and single cavity. I have ones made by

Lyman,

Redding/SAECO,

RCBS and custom ones from

Brooks Tru-Bore (Steve Brooks), Hock Moulds (Dave Farmer) and

Buffalo Arms.

A great many of us avid BPCR competitors have grown old along the way, so the NRA incorporated a scoped class to its BPCR games. NRA rules call them long tubes with no-click adjustments. Montana Vintage Arms offers scopes ranging from 23 inches to 30 inches. For years, only 6x was available but more recently, MVA has added a 10x version. Another company from Oklahoma named DZ Arms offers 8x scopes with NRA legal mounts. One of my .45-70 high points was winning the scope division of Shiloh’s 2017 Invitational match at their private Montana range. Again, I used the Shiloh won in 2006.

This is a vintage Sharps Model 1874 .45-70. The cartridges shown are the many chamberings the original Sharps Rifle Company offered. After trying all, Mike believes the .45-70 is the best.

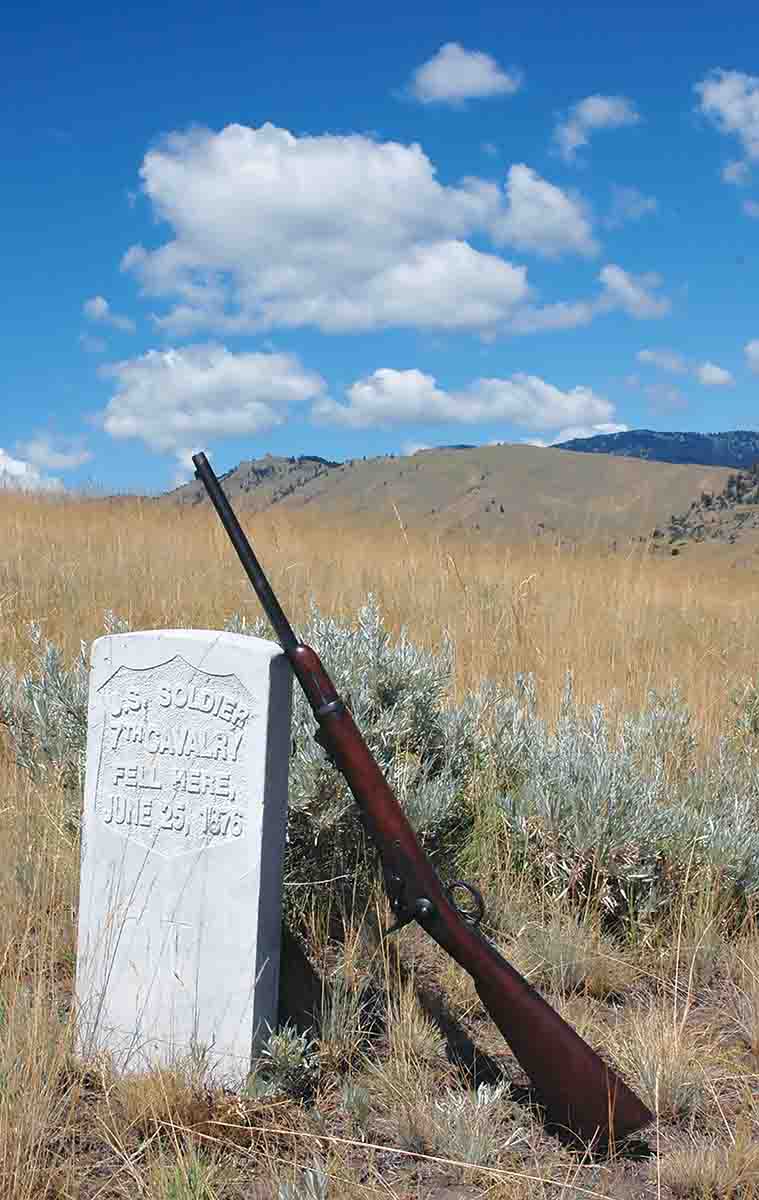

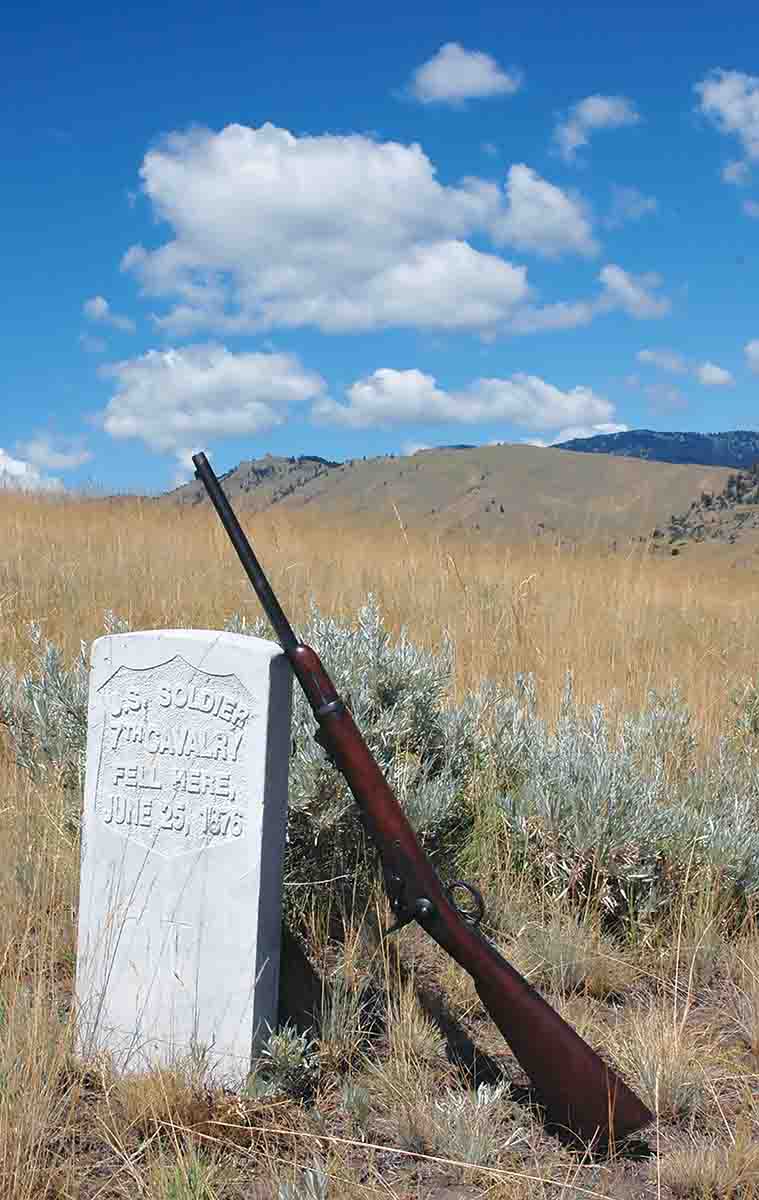

My single most memorable .45-70 shot happened in October 2016. A Los Angeles-based crew was filming near the Little Bighorn Battlefield and wanted someone to try duplicating a possible shot by a cavalryman at an Indian warrior 325 yards steeply downhill. Most of the film crew thought it impossible with such an old firearm. Kirk Stovall was involved and said, “Let’s get Mike Venturino to try it. He has an original carbine and knows black-powder reloading.” So at sunrise that morning, we were on top of a ridge with one of my steel PT Torso targets below. When the film crew finally got set up, I shot using the same bullet used in my first .45-70 handloading, i.e. Lyman 457124. It hit the target dead center for windage and a few inches low for elevation. Kirk was spotting for me. During the film crew’s cheering he leaned over and said, “You know that was luck.” I said, “Yeah but those city guys don’t know that.” Until nearly sunset, I was filmed firing 75 more rounds and get this – when the documentary appeared on television in 2019, not one second of that shooting was shown!

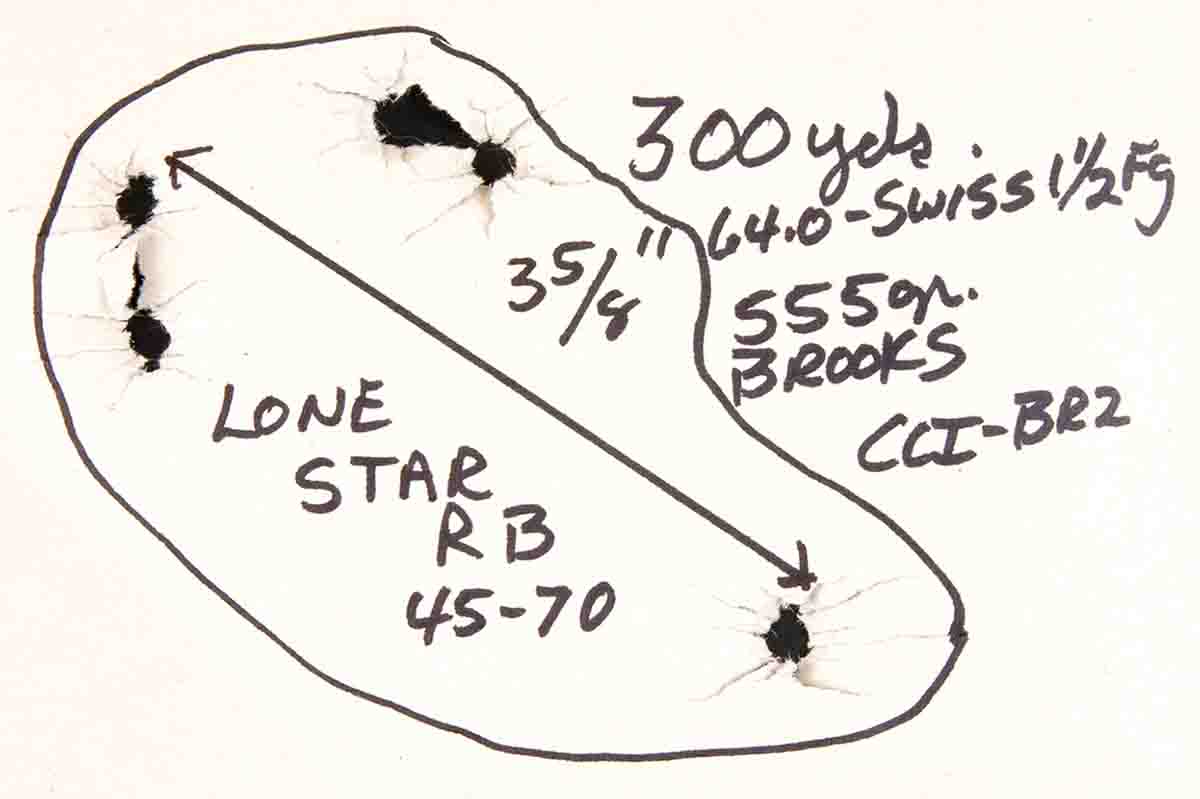

This group fired at 300 yards is about what Mike would accept for competition with .45-70 single-shot rifles.

So after 50 years of .45-70s, where do I stand? My .45-70s are down to four – the Springfield Model 1873 carbine bought in 1975, a Springfield Model 1873 infantry rifle that came along, my 1870s vintage Sharps Model 1874, and of course, my wonderfully accurate 2006 prize Shiloh. The U.S. Army got it right; .45-70 is the best of all old, big-bore black-powder cartridges.

Here are some of Mike’s favorite bullets for .45-70 single shots: (1) an original 1880s military load with 500-grain bullet, (2) a 500-grain RN from Steve Brooks custom mould, (3) a 530-grain RN from RCBS mould 45-530-RN and (4) a 560-grain RN from Steve Brooks custom mould. The loaded round at far right is one of Mike’s competition handloads using the latter bullet.

Mike believes that these two cast bullet designs are naturals for .45-70 leverguns. When using black powder, he chooses Lyman 457193 (left). When shooting smokeless propellants, he chooses RCBS 45-405-FN gas check (right).

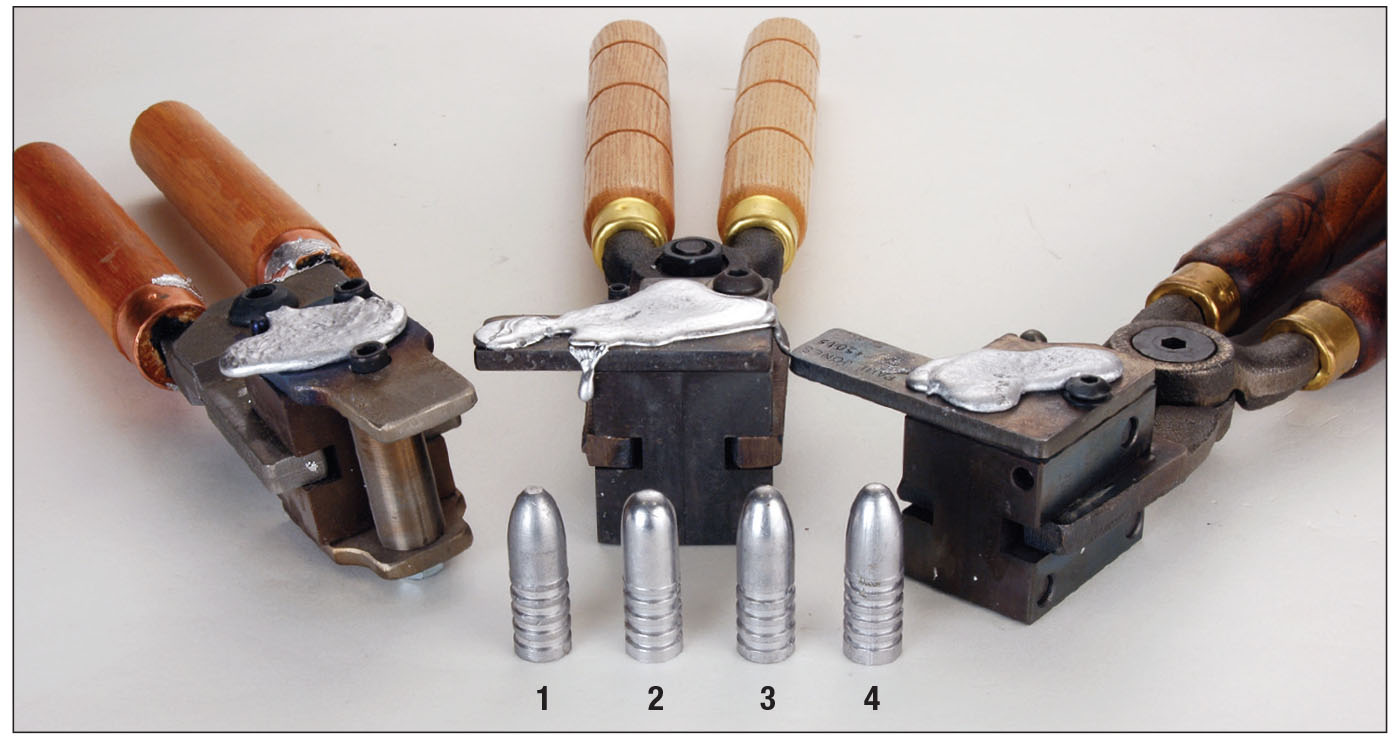

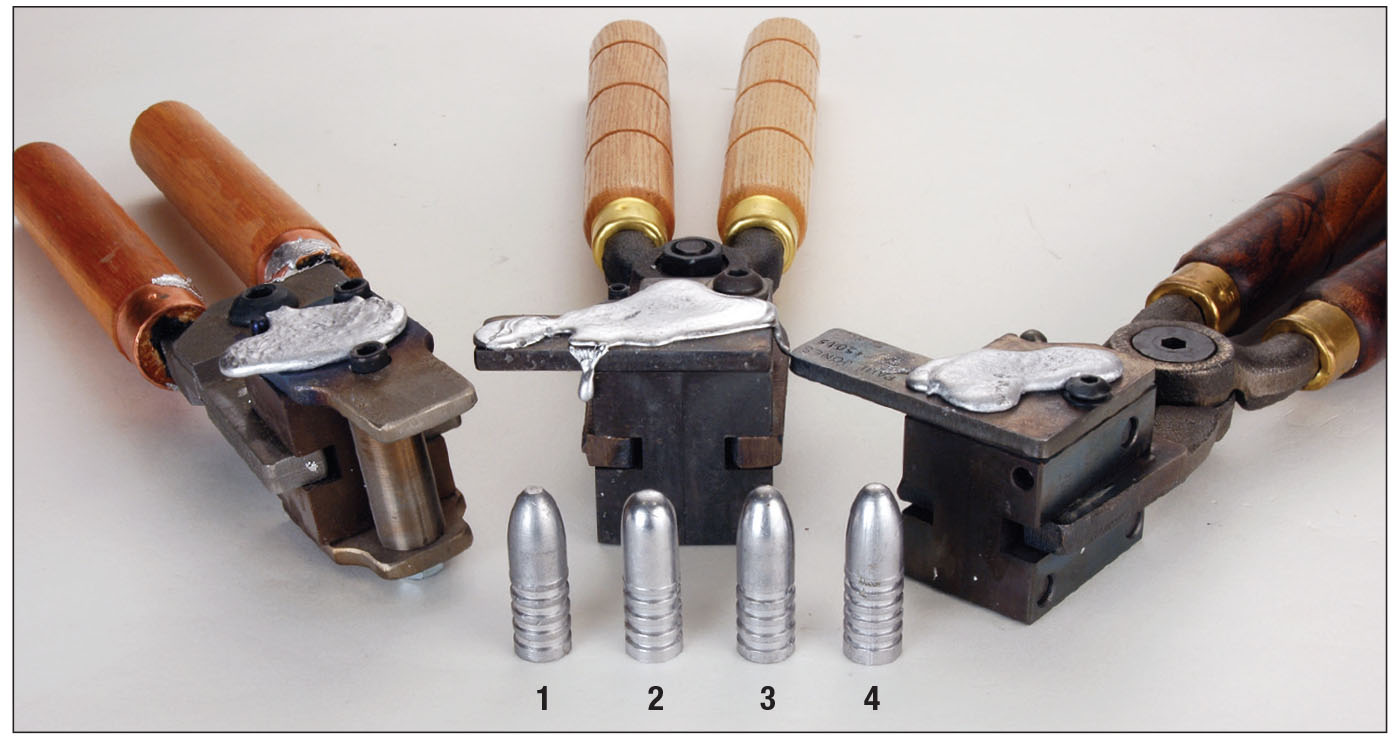

Mike’s preference for good .45-70 long-range target bullets are iron moulds of single cavity. The moulds are (left to right): a Hoch mould, a Steve Brooks custom mould and a Redding/SAECO mould. The bullets are: (1) Redding/SAECO No. 745 (530-grain RN/FP), (2) Steve Brooks custom bullet (555-grain RN), (3) Hoch (545-grain Creedmoor) and (4) Brooks custom bullet (560-grain Creedmoor).

.jpg)