In my last column,

Handloader No. 341 (December – January 2022), I looked into the events that led up to the introduction of the Winchester Model 1894 rifle in 1894. The original chamberings were the black powder .32-40 Winchester and .38-55 Winchester. The following year, the Winchester catalog listed two new cartridges, the .25-35 Winchester Smokeless and the .30 WCF Smokeless, that was all. The text didn’t even include the word “new.” Did someone forget to inform the marketing department? Perhaps there was a reason.

At this time, the new 6.5mm smokeless military cartridges were being used on the largest game. The sporting press was full of testimonials that read something like this: “As the lion came for me, I fired a shot into its breast, whereupon the beast rolled upon its nose, dead as a stone! These smokeless rifles are magnificent! I shall buy six more and use them henceforth forever.”

Naturally, there were other opinions, such as, “In need of camp meat, a snowshoe rabbit was shot at about twenty-five yards. It jumped up and ran into the forest. I tracked it for two days before losing it. These smallbore smokeless rifles are as worthless as a bucket of pond scum. I destroyed mine immediately!”

It is understandable why Winchester might want to go slowly. Allow the rifle and cartridge to acquire a bit of practical use, then make changes if necessary.

Commonly seen used .30-30 Winchesters these days are the Marlin M336 (top) and the Winchester M94 Angle Eject with plastic stock (bottom).

This appears to be what was done as the 1897 catalog contained comment by a chap named Theodore Roosevelt. He shot an antelope at “180 yards running; I struck him in the flank, the bullet ranging forward and coming out the opposite shoulder, bringing him down before he made another jump.” Then a fellow from Montana shot three deer, one at 425 yards, one at 275 and one at 175. “The one at 275 turned a complete somersault and dropped in her tracks.” In shooting all five deer, the rifleman “did not change his sights, which were set for 100 yards.” About all one can say is that this fellow was a politician in training!

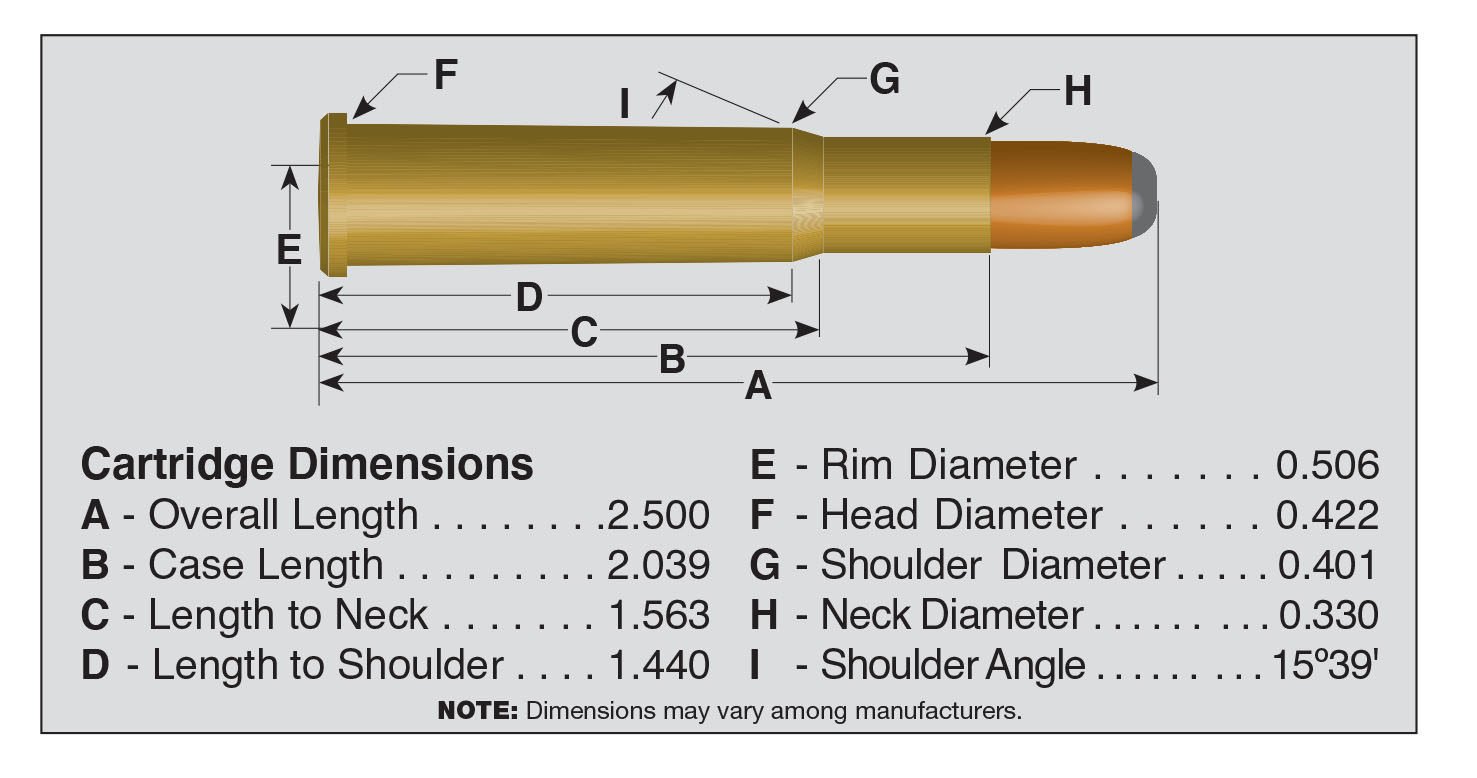

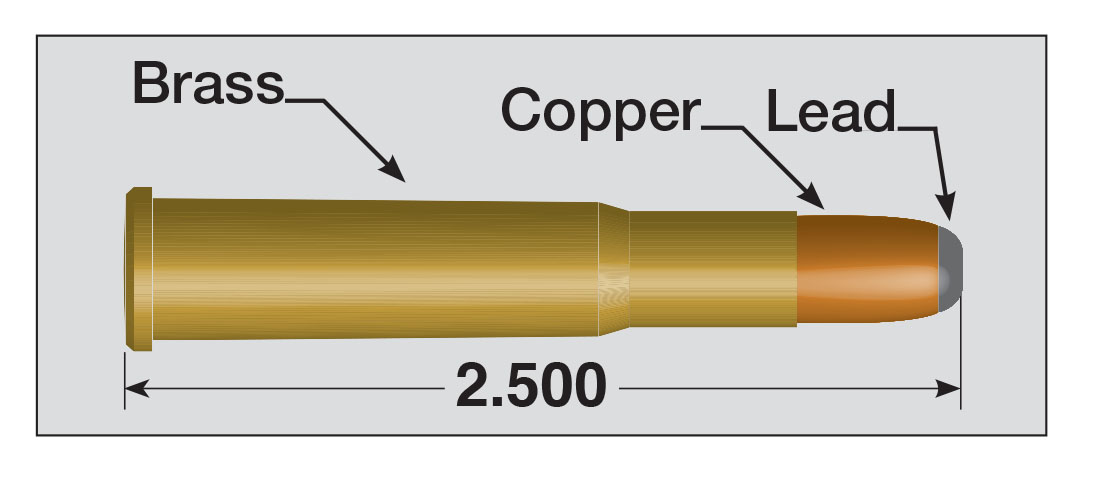

The .30-30 Winchester cartridge was sized to just fit the Model 1894 action with no extra space remaining.

The popularity of the .30-30 Winchester was not instantaneous. Hunters wrote to sporting magazines complaining of blood-shot meat and bone splinters. These were folks used to shooting deer in the woods at less than 100 yards. Big bullets at black-powder velocities worked just fine. The .30-30 Winchesters addition of 600 to 700 feet per second (fps) to impact velocity simply caused more damage.

The Winchester original loading used 30 grains of smokeless to push a 160-grain, thin-jacketed, full patch, roundnose bullet to 1,970 fps muzzle velocity (26-inch barrel) and 1,400 foot-pounds of energy. January 1896 saw an identical, but softpoint bullet added. The following year, a cartridge titled “Short Range” appeared containing 6 grains of smokeless behind a 100-grain pure lead bullet. Its purpose has never been explained and it was dropped in 1925. In 1904, the 160-grain slugs became 170 grains. Muzzle velocity increased to 2,008 fps and increased again in 1925 to 2,200 fps, with 1,826 foot-pounds of energy.

A .30-30 Winchester case ejecting sideways from a Winchester Model 1894 Angle Eject rifle, instead of straight up as in all previous Model 1894s. This allows for standard scope mounting.

Of course, the .30-30 Winchester had its competitors. Old black-powder rounds like the .32-40 Winchester and .38-55 Winchester soon had smokeless loadings. There was the .303 Savage, but hunters seemed to either love or hate the Model 1899 Savage rifle. Remington made the .30 and .32 Auto rounds, but again, it was the rifles. Remington’s pumps and autoloaders weren’t as well-liked as Winchester and Marlin leverguns.

In 1925, a new .30-30 Winchester load appeared called the Winchester Superspeed Cartridge. It drove a 110- grain jacketed hollowpoint 2,250 fps for 1,590 foot-pounds of energy. The purpose of the thing was “to meet the requirements of those shooters who desire a higher velocity.” Okay, but for what? Certainly not a game load. Varmints? Consider the rifles it was fired in. It lasted until World War II.

It started in the 1930s and was in full swing following the war. Gun writer topics became “bullet shock” and “one-shot-kills.” Obviously, the bullet was the important part here. Increasing attention accelerated bullet design to prevent premature breakup, yet allow adequate penetration. This was done by varying jacket thickness and forming belts, rings and cannelures both in and on the bullet jacket. Success was spotty for 3,000 fps rounds, but worked quite well for the .30-30 Winchesters 2,000-2,200 fps impact speeds. Of course, all these bullets had to have names. Soon, the terms Hi-Shok, Super-Shock, Core-Lokt, Inner-Belted, Silver Tip, Power-Point, Tri-Clad and a dozen others were common on .30-30 Winchester ammunition boxes.

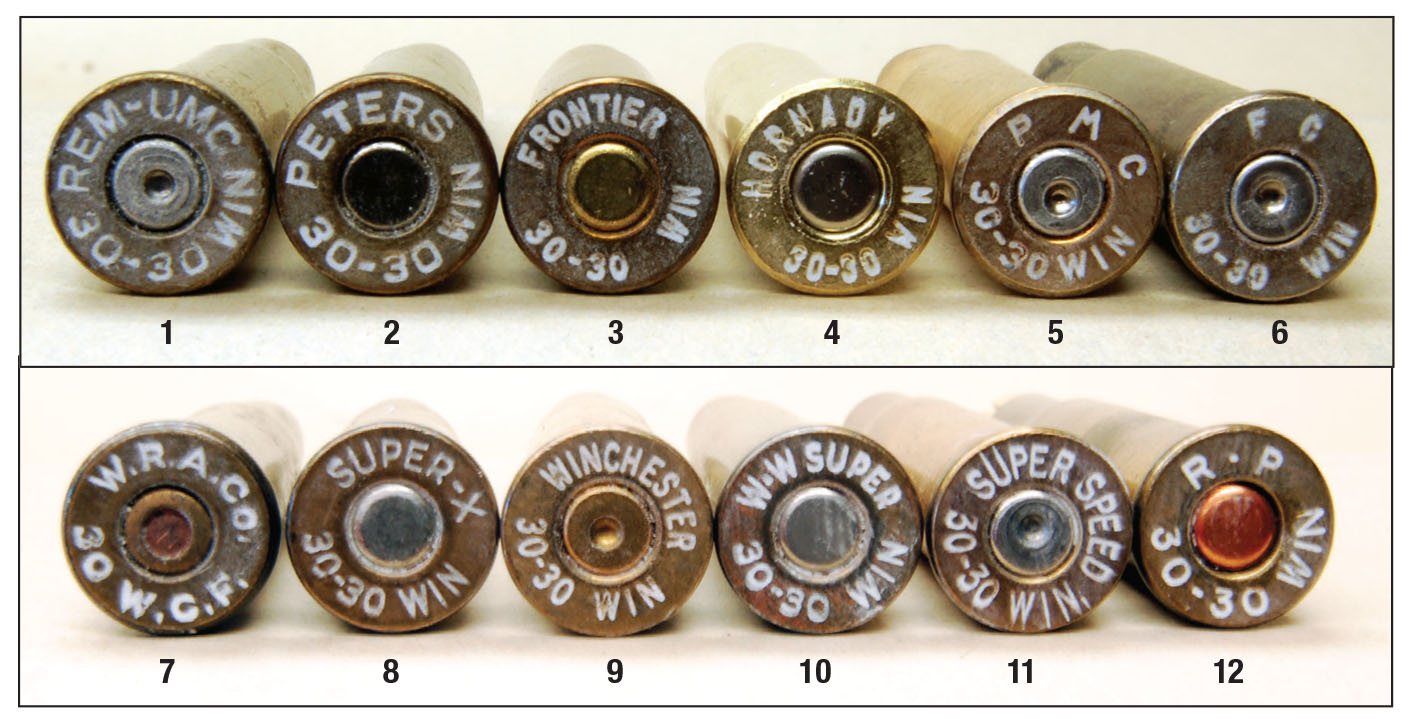

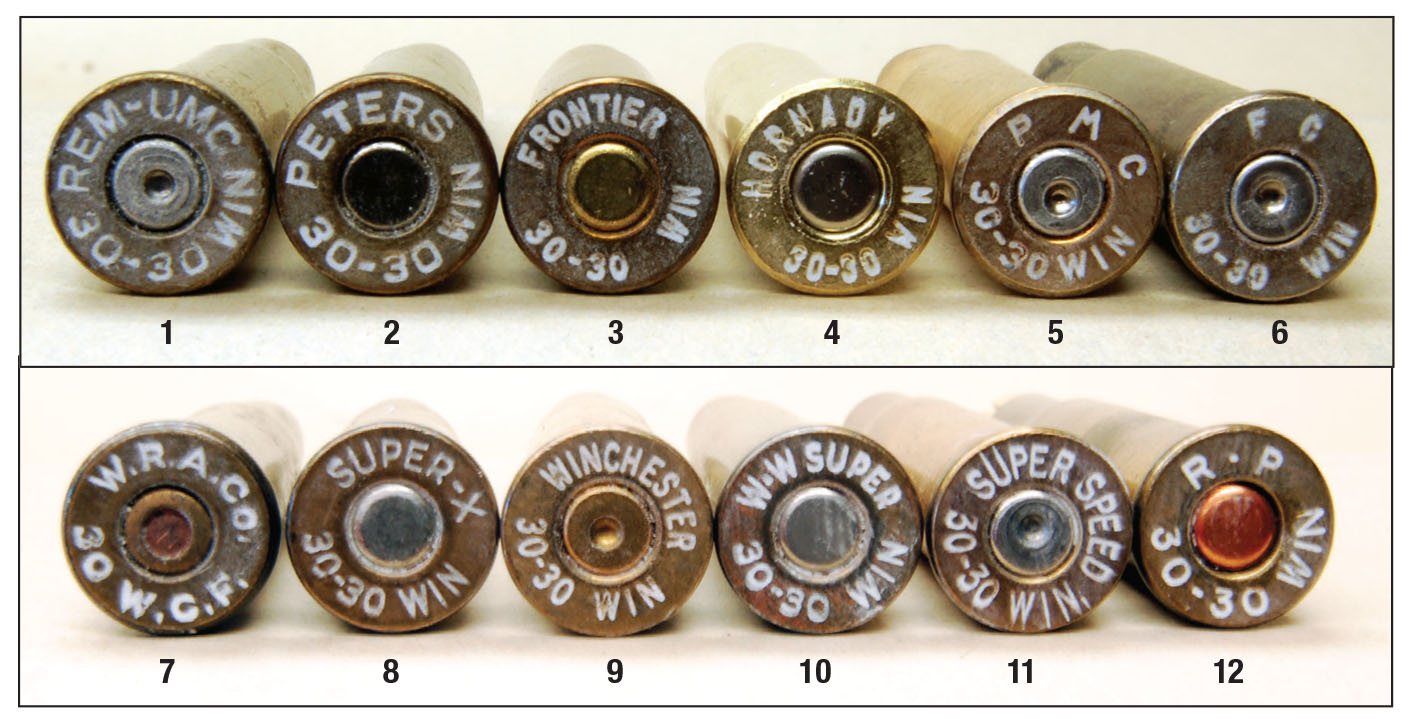

Some common headstamps found on .30-30 Winchesters are the (1) early Remington, (2) Peters Cartridge Company, (3) early Hornady, (4) today’s Hornady, (5) Korean import, (6) Federal Cartridge, (7-11) Winchester and (12) today’s Remington.

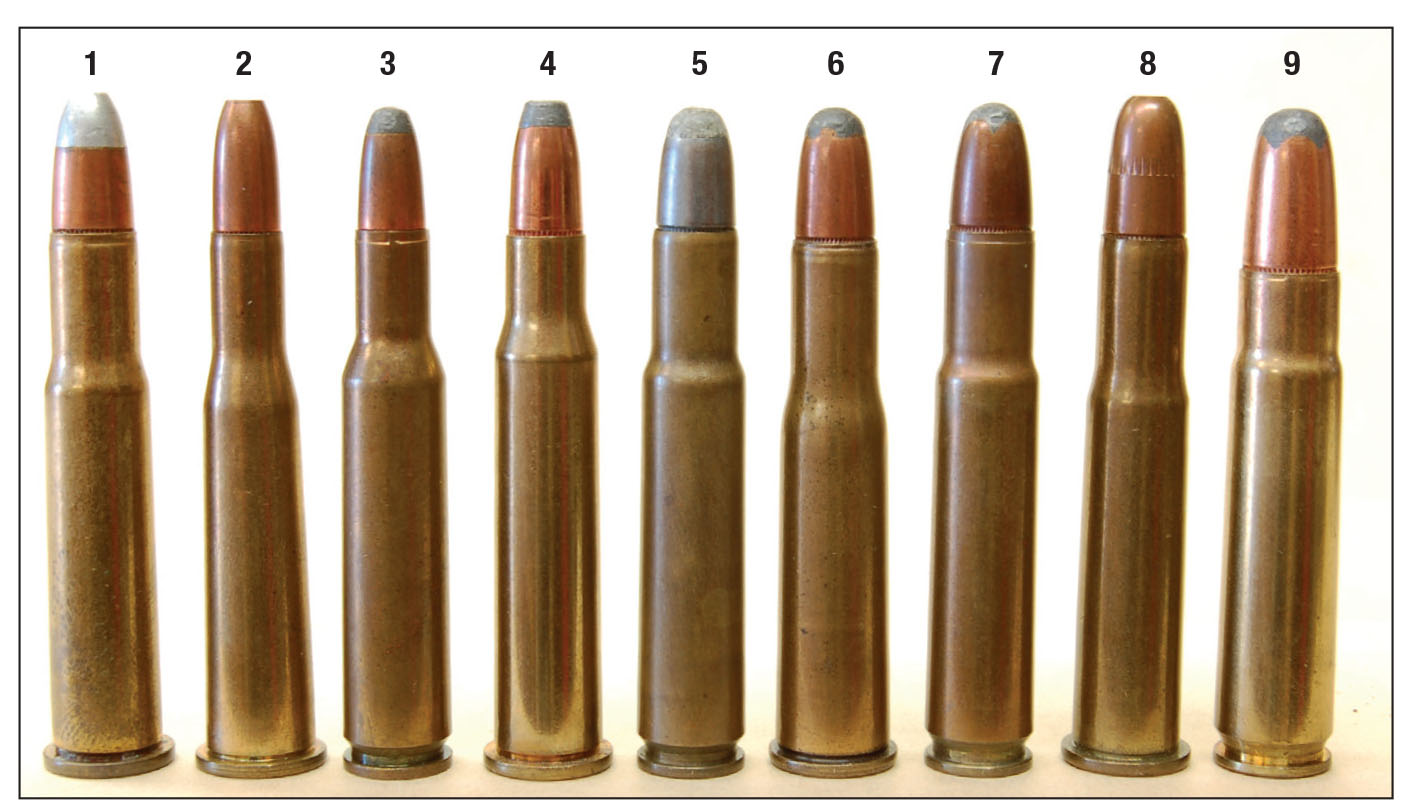

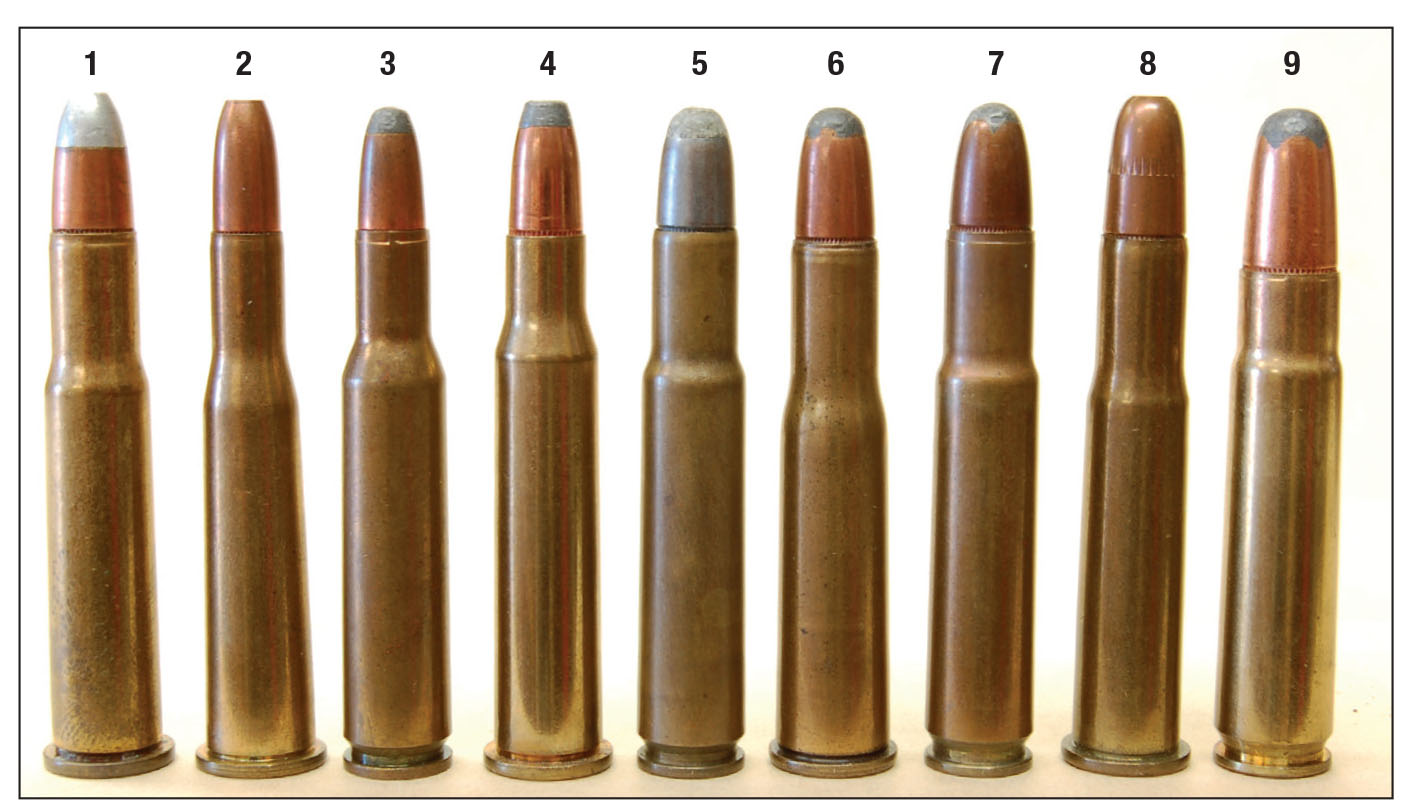

Competitors of the (1) .30-30 Winchester included the (2) .25-35 Winchester, (3) .25 Remington, (4) 7-30 Waters, (5) .30 Remington, (6) .303 Savage, (7) .32 Remington, (8) .32 Winchester Special and (9) .35 Remington. Only the .35 Remington is seen today.

The developmental history of the .30-30 Winchester cartridge essentially ended in the 1960s with perfection of these drawn jacket, lead-core bullets. A 150-grain bullet was driven at 2,400 fps, a 170-grain bullet listed a little over 2,200 fps. Why was this? Because not only does the design of the Winchester Model 1894 limit working pressure, but others also chambered rifles for the .30-30 Winchester. Savage, Harrington & Richardson and more offered rifle barrels for its single-shot, break-open shotgun actions. Obviously adequate at the time, these cast actions don’t allow ammunition pressure increases.

The (1) .30-30 Winchester compared to the (2) modern .260 Remington, (3) .307 Winchester, (4) .356 Winchester and (5) .358 Winchester, which are all more powerful than needed for woods ranges.

There have, however, been two totally different loadings. One appeared in 1979. Called the Remington Accelerator, it consisted of a .30-caliber sabot holding a 55-grain, .22-caliber bullet. Muzzle velocity from a 24-inch barrel was listed as 3,400 fps. Sighted 2 inches high at 100 yards, it was on at 200 yards and 10 inches low at 300 yards! A fellow once told me he tried them in a Model 1894 Carbine for called-up coyotes. Accuracy was poor, limited shots to 100 yards. Someone must have liked the rounds, however, as they weren’t dropped until 2009.

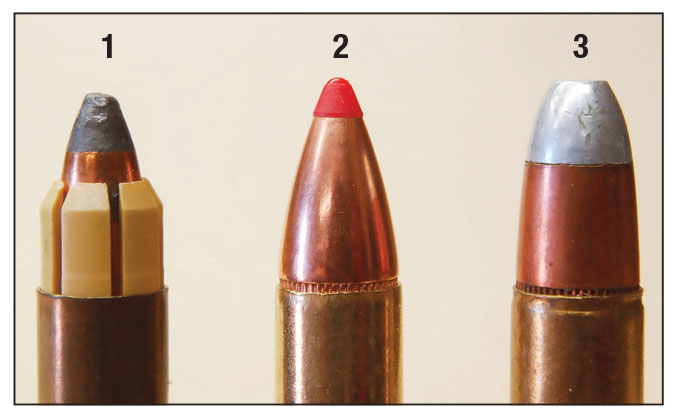

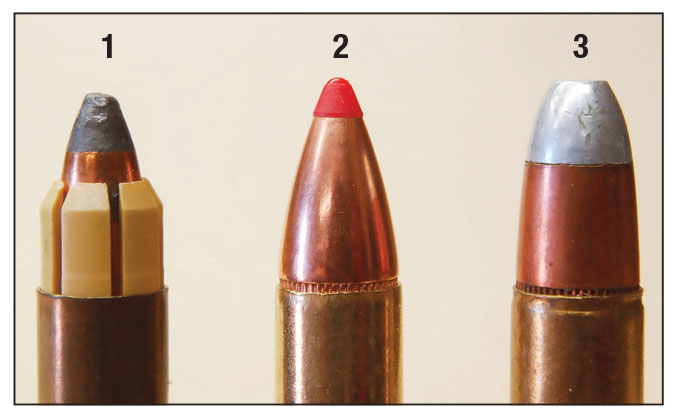

The second cartridge is far more important because it improves the .30-30 Winchester’s field performance. In 2005, Hornady announced a cartridge called LEVERevolution. It features a 160-grain bullet (called the Evolution and later, Flex Tip) moving at the standard 150-grain .30-30 velocity of 2,400 fps from a 24-inch barrel. Samples I have fired came in a bit under this, but such is common, given the uncontrollable variables ordinary shooters have to put up with when measuring muzzle velocities.

Of more importance is that Evolution/Flex Tip bullet. It is pointed, increasing ballistic coefficient nearly 75 percent over standard .30-30 Winchester slugs. It also has the now ubiquitous plastic tip, but this tip is made from an elastomeric polymer formulated to be soft enough to compress under the shock of recoil in a tubular magazine. The possibility of a bullet igniting the primer of the round ahead of it is eliminated.

The unique (1) Remington Accelerator and (2) Hornady Flex Tip bullets compared to the (3) 60-plus year standard Winchester Silvertip.

A .30-30 Winchester cartridge loaded with such a bullet is a different round entirely. Normal 150- or 170-grain loads don’t quite carry 1,000 foot-pounds of energy to 200 yards. The 160-grain Flex Tip bullet retains just over that figure at 300 yards. Regarding trajectory, classic .30-30 loads must be sighted 4-inches high at 100 yards to be on at 200 yards and 16-18 inches low at 300. The Hornady round needs only 3 inches up at 100 yards to be on at 200 and a foot low at 300.

The question now becomes whether the LEVERevolution ammunition makes the .30-30 Winchester a 300-yard (or greater) deer cartridge. Certainly, installing a scope with enough magnification to count a deer’s ear ticks at 500 yards wont make it so. Field conditions and individual rifle accuracy are more important. The .30-30 Winchester is not a .308 Winchester and never will be. One thing is certain, however. It is often stated that more deer have been taken by .30-30 Winchesters than any other cartridge. Given yearly ammunition sales and the Hornady cartridge, this isn’t going to change any time soon.

These were considered inexpensive .30-30 Winchesters 50 years ago. A Stevens M325 restocked (top) and a Savage M219 built on a break-open shotgun action (bottom).

.jpg)