.280 Ross

The First Big Seven and the Pursuit of Velocity

feature By: Terry Wieland | October, 17

Read some books from that era and you’ll come across references to “taking a coarse bead” or “drawing a fine bead.” If the hunter judged that his quarry was 500 yards away, he would place the bead in the center of the V notch – a normal sight picture. If it was closer – say, 200 yards – the bead would be drawn down into the V, lowering the muzzle and trajectory; if it was farther, the bead was raised above the V, elevating the muzzle. Simple.

The Ross M10 straight-pull hunting rifle was a wonder of the age, and were it not for the untimely intervention of World War I (1914-18), it might have gone on to have quite a different career. As it was, the war sank the military version of the rifle and Ross Rifle Co. with it, leaving the .280 Ross an orphan in search of a home. Fortunately, it was a great cartridge and had no trouble finding one. In fact, it found several.

Sir Charles Ross was a wealthy Scottish baronet who grew up stalking stags on his family estate near Inverness. He became interested in guns and determined to design the ultimate hunting rifle. Being an admirer of Ferdinand von Mannlicher, Ross leaned toward straight-pull designs. Being an aristocrat, he also had connections so formed an alliance with Charles Lancaster, the great London gunmaker, to produce rifles of his design.

Ross had many virtues, but also many vices. He was brilliant and talented but impatient and intolerant. Having burned through the family’s ready cash by his twenty-first birthday, he was land rich but cash poor. He raised money against the estate and invested in different businesses, among them a riflemaking company in Connecticut.

It is impossible to completely disentangle the fortunes of the Ross rifle from the .280 Ross cartridge, and the two of them from the life and loves, conflicts and controversies of Sir Charles Ross himself. All are intertwined and interdependent. In 1902, Ross convinced the Canadian government that it needed a Canadian- produced military rifle to arm its militia and the North-West Mounted Police. He set up a manufacturing facility near Quebec City, moved skilled craftsmen north from his factory in Connecticut, and went into production.

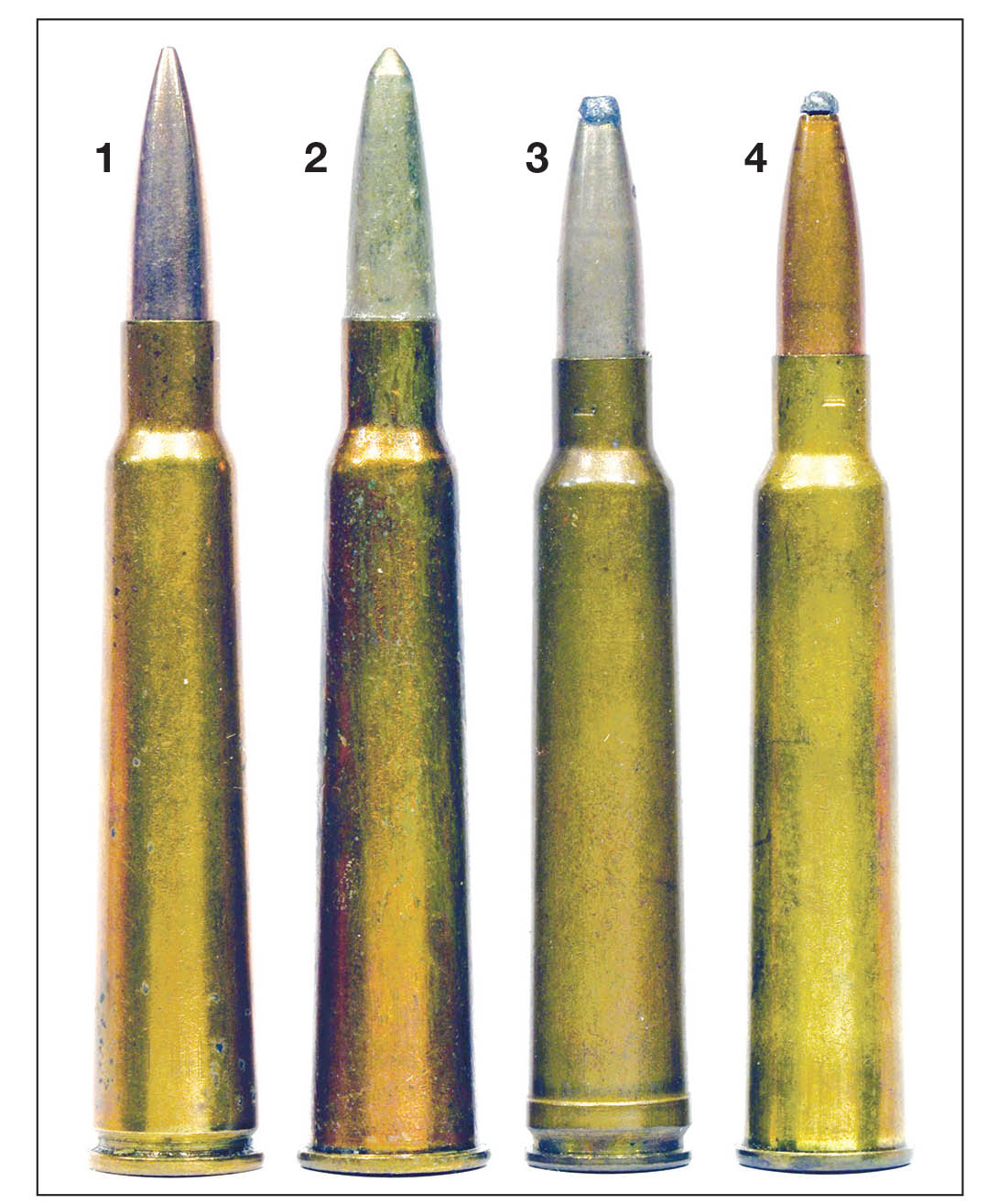

From the beginning, the Ross straight-pull designs were more like target rifles than military or hunting rifles. They were initially chambered for the .303 British, but Ross wanted to design the ultimate long-range cartridge. From studying von Mannlicher, he concluded that a 7mm cartridge was the answer. Around 1905, with the 7x57 Mauser (aka .275 Rigby) gaining in popularity, Ross decided to up the stakes. First, he designed what he called the .28/06, a 7mm designed in 1906. It resembled a .30-06 necked down, but there were dimensional differences and Ross’ cartridge was semirimmed. It did not deliver quite the velocity he wanted, so he decided to go bigger.

Ross’ colleague in designing ammunition was Frederick W. Jones, one of the foremost ballisticians and long-range shooters of the age. During his long career, Jones worked for the New Explosives Company, Eley Brothers, Nobel and the British government. In 1898, at the age of 31, he patented a process for coating smokeless powder to regulate burning rate. Col. Schultze (of Schultze Powder fame) called him “the father of smokeless powder.” He wasn’t, of course, but his coating process made possible almost all the improvements that came later.

Jones was more than a scientist. From 1908 until his death in 1939, he was a member of the British Elcho Shield team. The Elcho Shield is an annual team competition shot at 1,000, 1,100 and 1,200 yards; by comparison, the Palma Match is 800, 900 and 1,000 yards.

The new cartridge was loaded with 58 grains of Neonite (not Cordite). Produced by the New Explosives Co., Neonite was a coated, guncotton-based powder in the form of black flakes. (Sir Charles Ross later persuaded DuPont to produce a new, slower powder called No. 10, for use in loading .280 Ross ammunition in America.)

Jones’ testing showed a velocity of 3,047 fps with a 140-grain bullet. Eley Brothers agreed to produce ammunition, and in 1907 it was unveiled to the world as the .280 Ross-Eley. This nomenclature was retained until 1912, when other cartridge companies began producing ammunition. Since then, headstamps have read either “.280 Ross,” or simply “.280.”

In 1907, F.W. Jones took a prototype .280 Ross target rifle to Bisley, not to compete, but simply to see how it performed. The Field magazine reported he made “a number of possibles,” and the Ross team set about producing a real target rifle for the 1908 matches. According to Ross biographer Roger F. Phillips, the Ross match rifle had a heavy barrel with a special leade that allowed a “push fit” for the bullet, similar to that used in Schutzen rifles. The long bullet was positioned to enter the bore precisely.

The .280 Ross-Eley match ammunition was loaded with a 180- grain spitzer FMJ bullet, also extra-low drag, with a muzzle velocity of 2,700 fps. Jones won five individual and aggregate long-range matches at Bisley in 1908. The British NRA (aka National Rifle Association of the United Kingdom) received a complaint from aggrieved competitors and found the Ross rifle barrel was a couple ounces too heavy. Jones returned the silverware, but the Ross rifle retained the glory.

From that moment, the .280 Ross became the most influential cartridge in the world. Other makers began chambering it in both hunting and match rifles. King George V took a pair of .280 rifles on a hunting tour of India and reported them to be “a great success.” Less positively, George Grey (brother of the foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey) was killed by a lion in Kenya in 1911, after wounding it with a .280 Ross and failing to stop its charge. On his deathbed, he acknowledged that it was his own fault for getting too close, but the .280 takes the blame to this day.

Its more than 3,000 fps muzzle velocity inspired Charles Newton to design America’s first 3,000-fps commercial cartridge,

In London, Charles Lancaster & Co. chambered .280 Ross rifles with its famous “oval” bore and developed a rimmed version of the cartridge for use in double rifles and single shots. The War Office was so impressed, it commissioned a very similar military round, the .276 Enfield, intended to replace the .303, and a new Mauser-inspired rifle with an oversized action, the Enfield P-13, to accommodate it. It was never adopted, because war broke out in 1914, but it was adapted to the .303 as the P-14 and later the .30-06 (P-17). Both rifles saw use in both world wars.

The Mauser company in Oberndorf offered its magnum Mauser commercial rifles in .280 Ross. Later, the German-American ballistic fraudster, Hermann Gerlich, took the unaltered Ross case, renamed it the .280 Halger and embarked on his straight-out-of-fiction attempt to persuade shooters on both sides of the Atlantic that he was getting impossible velocities.

Although the Ross Rifle Co. closed before 1918 and new Ross rifles disappeared from the market, the cartridge (by its various names) became a standard of the English gun trade. Ammunition was manufactured on both sides of the Atlantic and stayed in production by Kynoch until 1967.

There are two immediate problems with shooting a .280 Ross rifle. One is brass, the other is bullets. Although new factory brass is occasionally available, the key word is occasionally. When it can be found, it’s expensive. Quality Cartridge (www.qual-cart.com) lists it, and Bob Hayley of Hayley’s Custom Ammunition, 1-940-888-3352 in Seymour, Texas, makes .280 Ross brass by swaging down and resizing .300 Remington Ultra Mag cases, resulting in good, reusable brass. Bob can also supply cast lead 140-grain spitzers.

Hayley’s remanufactured brass costs about $3 per round. Given the amount of reworking necessary, annealing the case necks before shooting is a good idea to prevent splitting. Once annealed, it lasts almost indefinitely with sensible loads.

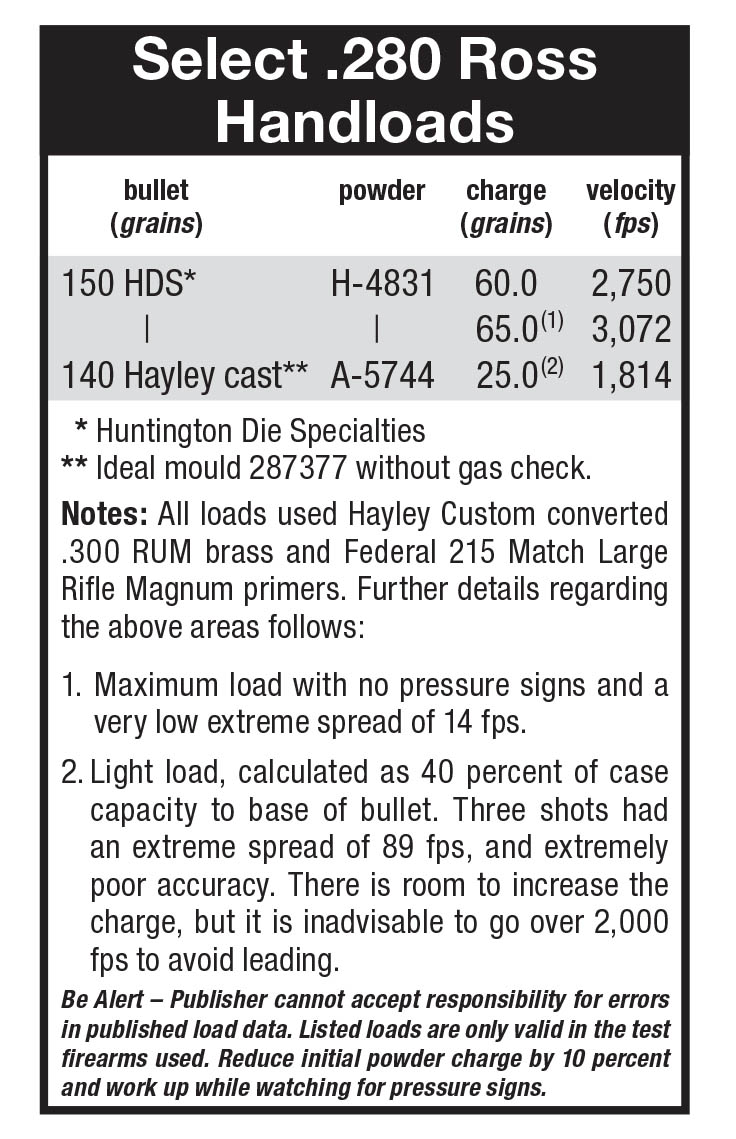

Powders are no problem. Hodgdon’s H-4831 is ideal for the Ross, and combined with Federal’s 215M primers, it is possible to reach original velocities with no adverse pressure signs. The 4350s do not work as well in the roomy Ross case; in my rifle, I get flattened primers before I get to 3,000 fps.

As for the 500-yard shots with the single folding blade, I’m working on targets at 300 yards for now. It is certainly educational.