Wildcat Cartridges

.300 H&H Ackley Improved (30 Degree)

column By: John Haviland | October, 17

After five years of handloading the .300 H&H Ackley Improved (AI) cartridge, I’ve learned not to take anything for granted. Reading what others say about a wildcat cartridge adds to the general knowledge, but it’s best to start in the shallow end of that pool and slowly wade deeper.

My .300 AI is a Winchester Model 70 made in 1950, and its original .300 H&H Magnum chamber was reamed out to “.300 H&H Ackley Imp.” as is stamped on the barrel. The rifle had been extensively altered, with its 26-inch barrel cut back to 24.5 inches and a Lyman barrel-band front sight and muzzle break attached to the muzzle. The left side of the receiver had been drilled, and a notch was cut in the stock, to accommodate a Pachmayr Lo-Swing scope mount to hold a Weaver K4 scope. The rifle is one of the lighter, standard pre-64 Model 70s I’ve ever held, with a weight of 8.75 pounds.

Making the first batch of .300 AI cases required a long and laborious process. Once-fired Federal .375 H&H Magnum cases were the only suitable cases available at the time. To form the cases, they were run partially into a .338 Winchester Magnum sizing die, then a .300 Winchester Magnum sizing die to step down the necks. The bottom of the necks were left a bit wide so cases entered the rifle’s chamber with only some downward pressure on the bolt handle. The cases were fully formed by loading and firing 77.0 grains of H-4831 with Speer 180-grain spitzer bullets.

My first assumption was .300 AI cases had a 40-degree shoulder angle since P.O. Ackley, in his book Handbook for Shooters & Reloaders, Volume I wrote, “The Ackley .300 Improved is the same as the .300 Weatherby except for minor details. The Weatherby has what is known as a venture shoulder (curved corners) while the Ackley has sharp corners and a 40 degree angle.”

I wrote to Kent Sakamoto, RCBS product marketing manager, to buy a set of the company’s special order full-length and seating dies. Kent wrote back that RCBS offered dies for two different .300 H&H Magnum Improved cases, one with a 30-degree and another with a 40-degree shoulder angle. To determine which shoulder angle was correct for my rifle, Kent suggested sending RCBS three cases from disassembled cartridges that came with the rifle, and three fired cases.

Kent got back to me a couple of weeks later and said my cases had a 30-degree shoulder angle, not the 40-degree angle I had assumed. “According to our technician,” he said, “they are not standard 30-degree Ackley Improved either. Headspace on your cases is short by about .019 inch, and the sizer will be produced accordingly.”

While waiting for the dies to arrive, I read Internet posts from several .300 Ackley shooters who wrote that the easiest way to form Ackley cases was from .300 Weatherby Magnum cases, because the only difference between the two was the shoulder. So I ordered 50 new Hornady .300 Weatherby Magnum cases. The RCBS dies arrived, and the sizing die was a perfect fit. I turned the die into the press a little bit at a time until the shoulders of the fireformed .375 H&H cases had been set back .002 inch. The shiny, new Hornady .300 Weatherby Magnum cases were about .01 inch shorter at the shoulder than Ackley cases. So all the Hornady .300 brass required was fireforming to convert their dished-out shoulder to the Ackley shoulder.

I mistakenly assumed the .300 AI’s throat included this freebore. Speer 180-grain spitzer bullets seated for an overall cartridge length of 3.53 inches (about as long a cartridge that fits in the rifle’s magazine) that were .20 inch short of contacting the rifling lands. So there was the freebore, I thought. Recently, I peered into the rifle’s barrel bore with a Lyman Digital Borescope. It showed the rifling began a short distance in front of the chamber but was severely worn. In fact, the first 10 inches of the lands were eroded to the point they looked like alligator skin.

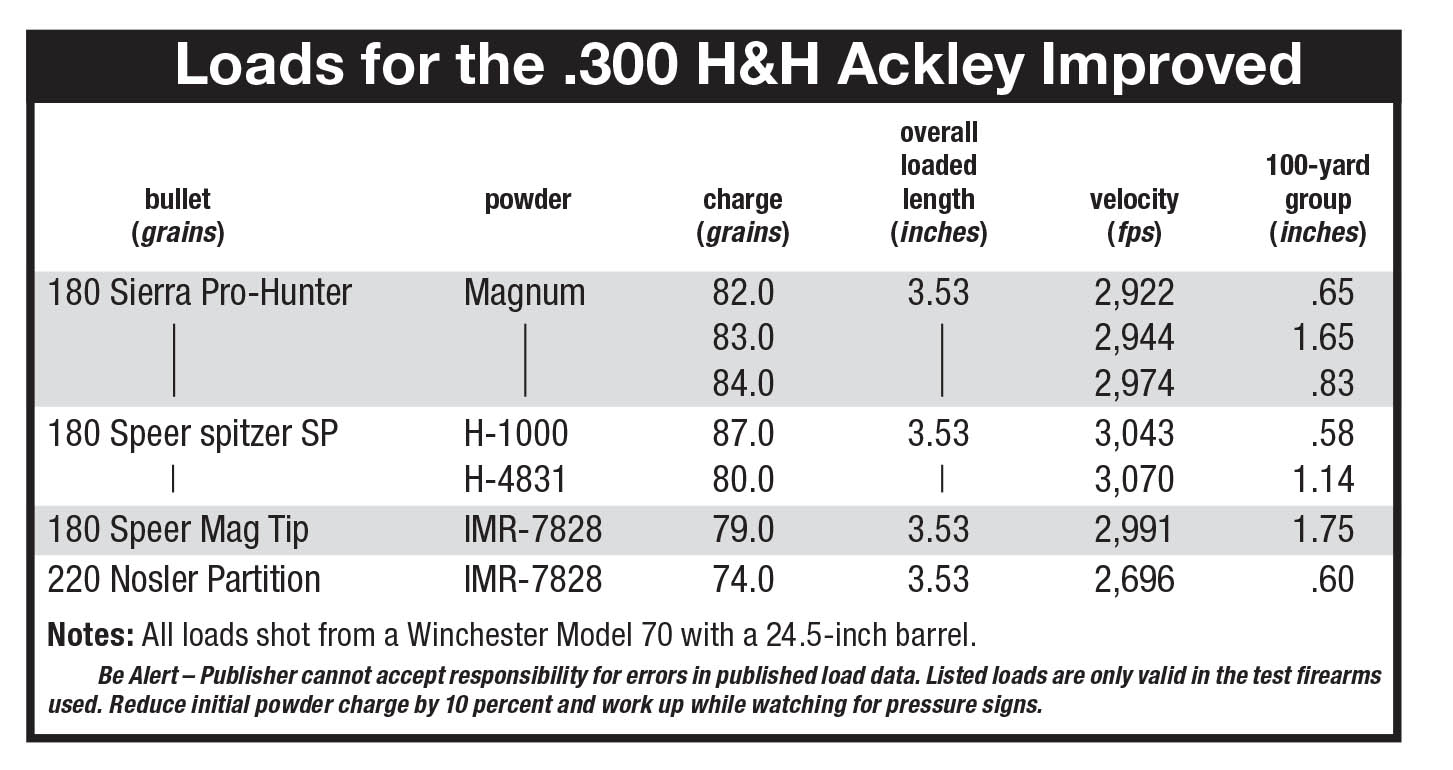

For full-power loads, I picked powder charges a couple grains below the listed maximum weights of H-4831 and H-1000 listed for the .300 Weatherby Magnum in Hodgdon’s Annual Manual with Speer 180-grain bullets. Velocity registered close to the maximums Hodgdon recorded for the Weatherby, so my loads were a little hot.

Trouble resulted when assuming all bullets of the same weight and caliber produce similar pressures. I loaded 83.0 grains of H-1000 – what I thought to be a reasonable amount – with Hawk 200-grain spitzers in the .300 Ackley. The first, and only, shot with that combination locked the bolt shut tighter than a bank vault. The chronograph registered 3,059 fps. When the bolt was finally pried open, the case’s primer pocket was the size of a gopher hole, and the primer fell on the ground. Chosen charge weights of Reloder 25 and Hybrid 100 V also cratered primers.

Starting over, I dropped to 78.0 grains of H-1000, then up to 79.0 grains. This powder reduction decreased velocity a good 400 fps. That shows that large magnums, like the .300 Ackley Improved, must develop

I also courted trouble loading Nosler 220-grain Partition bullets. A load of 74.0 grains of IMR-7828 fired the Nosler bullets just short of 2,700 fps, and the face of fired primers remained round, and bolt lift was easy. But loads of 73.0 grains of Reloder 22 and 82.5 grains of Retumbo cratered the firing pin indent on the primers.

That taught me the middle charge amounts of powder listed for the .300 Weatherby Magnum in handloading manuals should be considered maximum for the .300 AI, and that starting on the light side of suggested powder charges and working up in increments is still wise advice. That’s

Meanwhile, the Winchester .300 AI rifle has fired 50 more of those top loads with ease and good accuracy, and it’s absolutely a reliable load.