In Range

Squeaky Clean Brass

column By: Terry Wieland | October, 17

Occasionally, one of those Brasso-ed, varnished cartridges shows up and, after 50 years, it looks far worse than if it had been allowed to age gracefully. For my part, I only used Brasso on newly-made cartridges that I was adding to my collection, and never maltreated the occasional really old one I came across, such as a .500 Express or .40-70 Straight Sharps.

Not being a metallurgist, I cannot say exactly what long-term effects certain chemicals have on brass. I do remember reading, way back then, that a superior method of cleaning brass was to use one of several mild acids that were then available, and I also distinctly remember the writer cautioning that they should only be used on cases that were not going to be reused.

As we all know, the composition of brass has changed over the last century. It looks different, it’s a different alloy and it is vastly superior for handloading. It is also known that reusing old brass fired with a mercuric primer, or even that sat unfired for long, is asking for trouble. Mercury makes brass brittle and liable to crack, and a case that cracks when fired is not a pleasant experience.

Brightness aside, there are good reasons for cleaning used brass. One is to remove powder fouling from inside the case (which may or may not ever present a problem in itself) that makes it difficult to examine case interiors for things like incipient case separation. Another is to clean the primer pocket and ensure that the flash hole is not blocked.

These are serious enough reasons for cleaning brass you have shot and carefully shepherded yourself. They are doubly serious if used brass is picked up on a range or purchased in bulk from a shooting facility. Even your own brass, ejected rather energetically from a semiautomatic into grass, gravel or mud, needs careful cleaning before it is loaded again.

Then there is the plight of the handloader who owns a rifle or pistol in an obsolete caliber for which he must search out brass in small lots on the Internet or in plastic bags at gun shows. The .303 Savage is a good example, because it is a cartridge that can’t be made from anything else, was purely a hunter’s cartridge in its day and was rarely reloaded. For .303 Savage fans, original brass is like the Golden Fleece, but any found will probably look pretty ugly and need careful cleaning and examination.

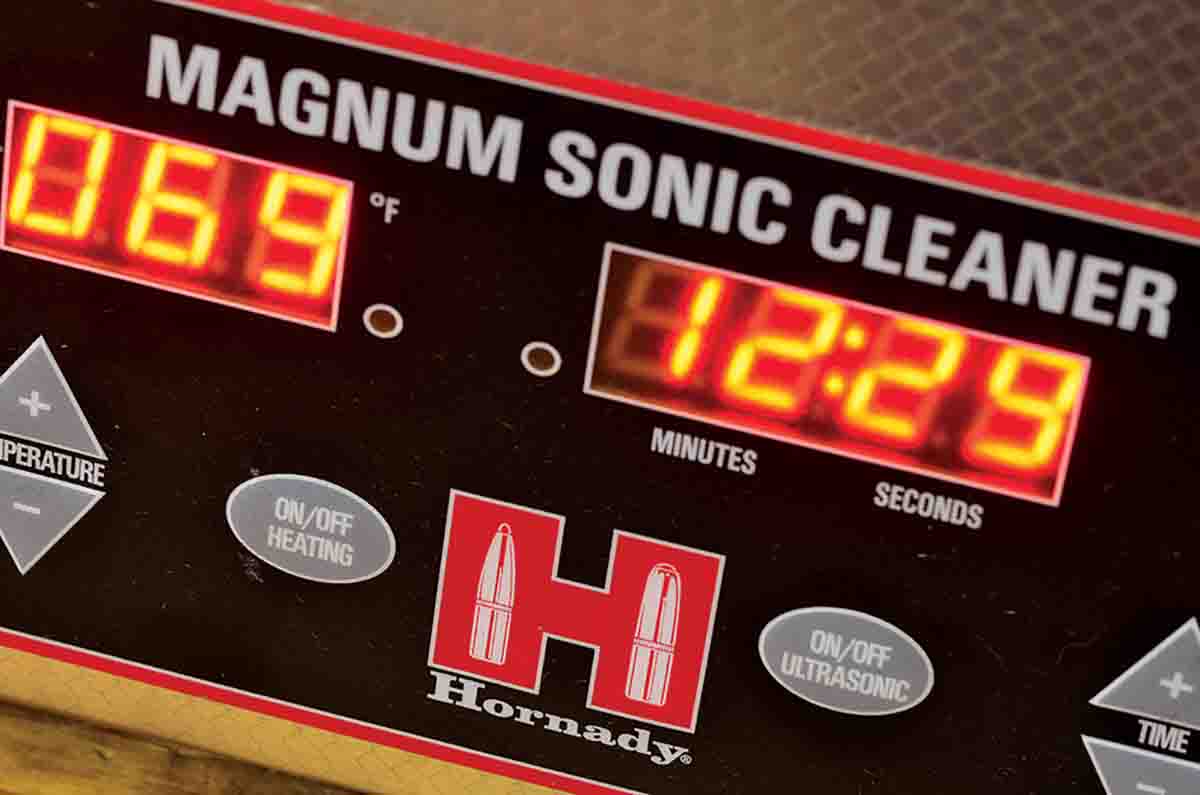

What I now do with brass like that is clear the primer pocket and flash hole, and brush out any obvious debris such as spider nests (it has happened!), caked mud and so on. I have even found pebbles lodged in case mouths. It then goes into a Hornady Sonic Cleaner. I’ve had one for four or five years – not the newest model – but it works well. Other handloaders I know will first put the brass in a dishwasher, held in a wire basket of some sort, or a mesh bag – never tried it myself. A powerful small hose is also useful to direct high-pressure spray into the case to get rid of “stuff.”

The sonic cleaner uses a brass-friendly chemical to remove traces of powder fouling, and after the brass comes out, rinse it with water. At this point, I put the brass straight into a Thumler’s rotary tumbler that was recommended by Larry Weeks, just before he retired from Brownells. I figured that, since Brownells sold everything, Larry had a good idea of what worked best. The tumbler has a rotating drum, into which water and dishwashing liquid are placed. It also contains a couple pounds of tiny stainless steel cylinders that look for all the world like H-4198 powder. They were originally made for polishing rocks used by jewelry makers. There are no sharp edges or corners, so brass remains unscratched.

The brass goes into the drum for an hour or so, after which you remove the screwed-down lid, clear away the soapy foam and start fishing out the brass. The only way I have found to do this is to take them out one at a time by hand, carefully shaking any of the tiny steel rods out of the case and checking to make sure none are lodged in the flash hole. This is laborious, but there seems no other way.

Marshaling the steel rods is a continuing pain, and this is where a good magnet comes in handy for picking up escaping rods from the sink. For ease of handling, it helps to rinse the brass – soapy brass is slippery – after which I put it in a brass dryer made by Competitive Edge Dynamics. This is both easier and faster than shaking all the drops of water out, then leaving it to dry. To avoid annealing issues, it is not a good idea to try to dry brass in an oven.

A session with the Thumler is rather laborious, and since it holds a lot of brass, I try to fill it to capacity. Do not mix cases that can lodge inside each other, or the small ones jam in the larger case necks. Also, after drying, every case should be carefully checked for lodged fasces of steel rods in the neck, or inside small, straight-wall cases like 9mm Parabellum.

Having said all that, the brass ends up squeaky clean and polished bright as a new penny. If a handloader uses a lot of rare, hard-to-find or expensive brass for odd calibers and treats empty cases like gold, it pays to spend the money for the right equipment. You’ll save it in the long run.