Winchester 572 Powder

A New Powder for 20-,16-, and 12-Gauge Loads

feature By: John Haviland | October, 17

Chris Hodgdon said Winchester 572’s niche is for subgauge shotshells. “[Winchester] 572 is just wonderful in the 28 gauge,” he said. “We didn’t have a Winchester powder in that burn rate. Winchester has a good following, and there are reloaders who will only use Winchester powders. Five-seven-two fills that missing link in the Winchester line of powders.”

Winchester 572 is similar to W-571, which Winchester discontinued before Hodgdon took over distribution of the powders in 2006. Not long after Winchester discontinued 571, Hodgdon stopped selling its equivalent, HS-7. “Five-seven-one was made with old technology and the market for it was slow,” Hodgdon said. “W-572 is more efficient, so you use less of it than the old 571. Plus, it is cleaner burning.”

I did not have the correct powder bushings for the charge weights of W-572 used for the 12- and 20-gauge loads I assembled. Instead, the correct amounts of powder were weighed and poured into cases on my RCBS Grand press for the 12 gauge, and a Hornady 366 press for the 20 gauge. My MEC 600 Jr. single-stage press for reloading 16-gauge shells is set up with a Multi-Scale Ltd. Universal Charge Bar (www.multi scalecharge.com) that adjusts to dispense 1⁄2 to 11⁄2 ounces of shot and 12 to 55 grains of powder. I have used it for years on several single-stage MEC presses, and it has saved me countless dollars in shot bars and powder bushings – and headaches searching for the correct bars and bushings for a particular load. I weighed 10 charges dropped from the Universal Charge Bar dialed to drop 23.2 grains of W-572. One charge weighed .30 grain heavy, two others weighed .20 grain heavy, and the rest were right on the money at 23.2 grains.

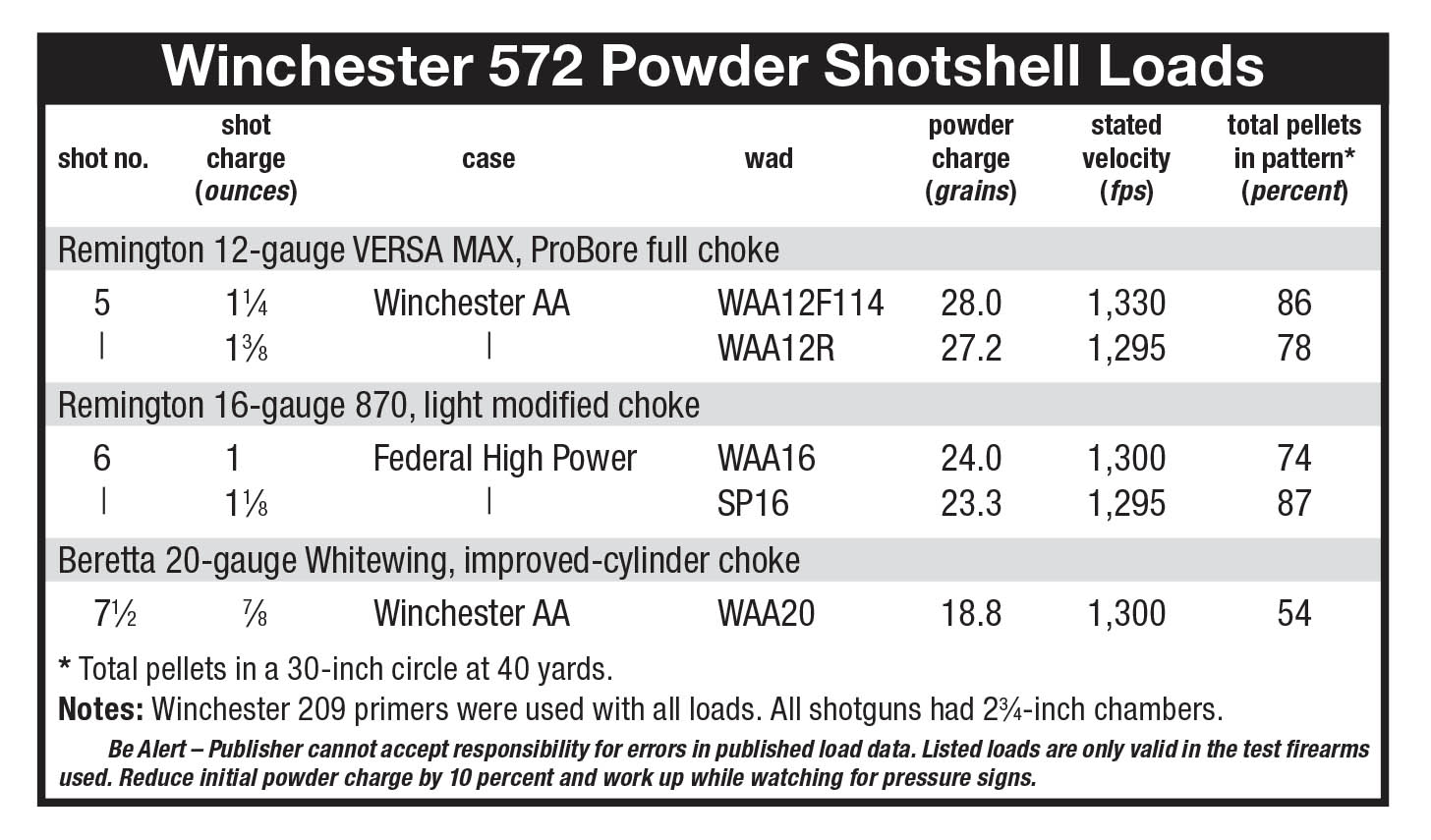

In addition to the 28 gauge, W-572 works well in a broad spectrum of shotshell and handgun cartridges. A Hodgdon press release states the powder has the correct burn rate to create a 31⁄4 dram equivalent, 11⁄4 ounce, 1,330 fps 12-gauge load with any brand of case. The powder also produces target and field loads for the 20 gauge and field loads for the 16 gauge. In addition, W-572 works well with a number of handgun cartridges ranging from the .25 Auto to the 9mm Luger, .38 Special, .44 Remington Magnum and .45 Auto. For this article, W-572 was used with lead shot in 12-, 16- and 20-gauge loads.

I substituted three wads Hodgdon’s website listed with data for W-572. For the 12 gauge, WAA12F114 wads (which have been

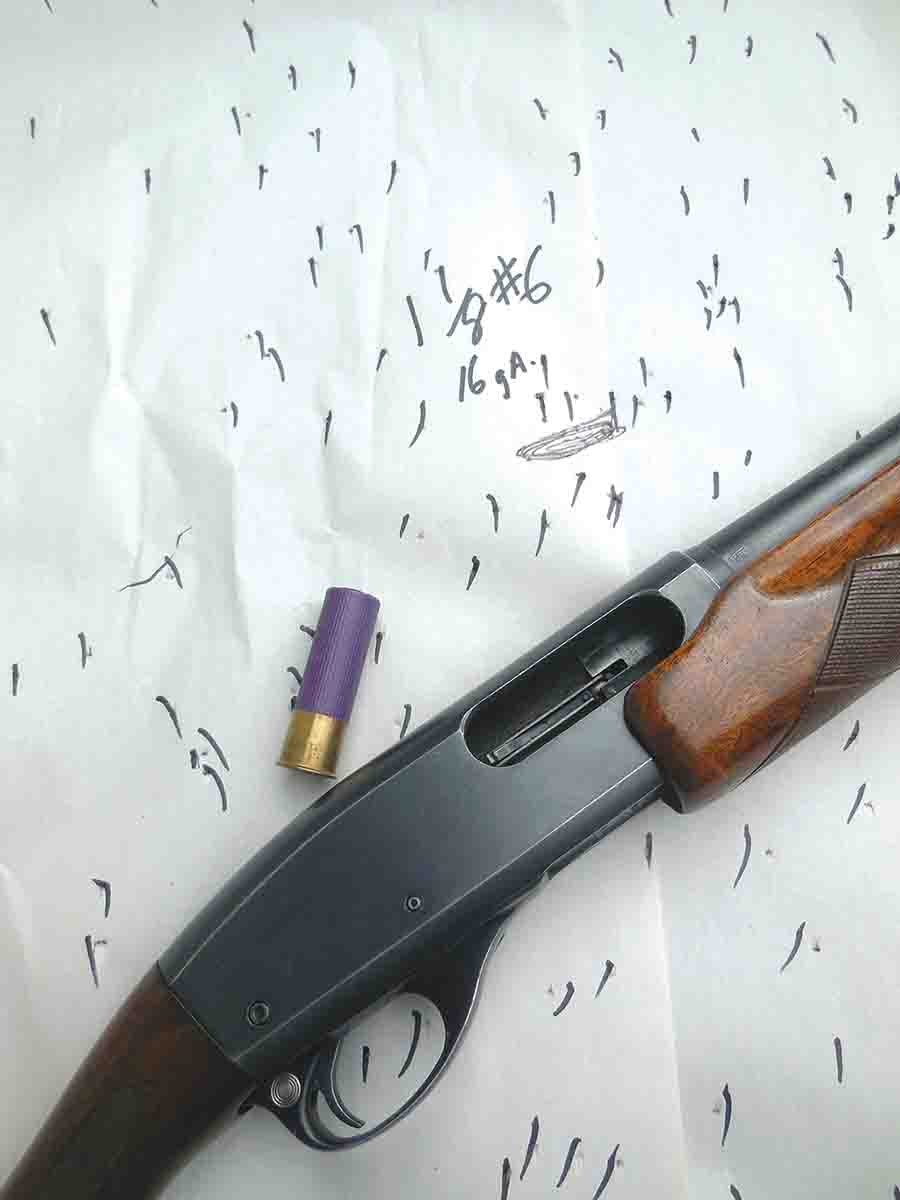

My wife carries a Beretta 20- gauge Whitewing when hunting ruffed and blue grouse. The over/under weighs a feather over 5 pounds, 10 ounces, and its recoil is distractingly unpleasant for Gail when shooting more than 7⁄8 ounces of shot. So I stayed with that shot charge when testing W-572 in the 20 gauge. However, I loaded 16- and 12-gauge shells right up to the maximum of shot and W-572.

The Hodgdon website lists a 20-gauge starting load of 15.5 grains of W-572 for a velocity of 1,150 fps and a maximum of 18.8 grains for a velocity of 1,300 fps for 7⁄8-ounce loads in Winchester AA 23⁄4-inch cases. The starting load produced light recoil from the Beretta Whitewing. It also cycled the action of a Beretta AL 391 Urika 2 autoloader. The maximum charge of W-572 had some bite to it, but Gail can brave that much recoil during a day of hunting.

The Beretta’s improved-cylinder choke placed 54 percent of a 7⁄8-ounce charge of No. 71⁄2, 6 percent antimony shot fired at 1,300 fps in a 30-inch circle at 40 yards. A grouse would never slip through such a pattern.

I used to believe such high velocities would increase shot spread compared to slower velocities. The reasoning was the stiffer jolt from the increased powder charge deformed more pellets, which made them fly wide. Additional wind resistance from the higher velocity also caused shot to flare. Patterning shot starting out at 1,200 and 1,400 fps showed no difference in pattern size at short distances. At 40 yards, the higher velocity did seem to spread the shot charge a few additional inches. However, centers of pellet density will shift somewhat from shot to shot. If I spent the tedious time to shoot a dozen shells at both velocities and evaluate their patterns, I might well have found that the spread difference was next to nothing.

The faster a ballistically inefficient lead pellet is fired, the faster it slows. A No. 71⁄2 shot pellet that leaves the muzzle at 1,300 fps has slowed to about 710 fps by the time it has reached 40 yards. In comparison, the same pellet fired at 1,150 fps trails the faster pellet by only about 55 fps at 40 yards. Furthermore, the faster pellet creates only about .2 ft-lbs of additional energy over the slower pellet at 40 yards.

Velocities of one and 11⁄8 ounces of shot in the 16 gauge were impressive with W-572. According to Hodgdon’s website, W-572 shoots one ounce of shot at up to 1,300 fps from Federal High Power cases. Hi-Skor 800x powder exceeded that velocity by a smidgen, and Longshot by 150 fps. W-572 fires 11⁄8 ounces of shot at up to 1,295 fps. Hi-Skor fairly well equals that velocity, and Longshot beats it by 50 fps. However, nearly four additional grains of Longshot are required for that gain over W-572.

Hodgdon’s website lists W-572 data for 11⁄4- and 13⁄8-ounce shot charges in 23⁄4-inch, 12-gauge shells; no loads are listed for longer 3- or 31⁄2-inch cases. I loaded Winchester AA cases with a maximum charge of 572 and 6 percent antimony No. 5 shot. The 11⁄4-ounce load had a stated velocity of 1,330 fps and patterned 86 percent of the pellets in a 30-inch circle at 40 yards from a ProBore full choke in the barrel of a Remington VERSA MAX auto-loader. There’s my late-season pheasant load when I stop my pickup at the edge of a field and open the door, only to see birds flying out the far side of the field.

For bird hunters who believe more shot is better, a 13⁄8-ounce load of No. 5s placed 78 percent of its pellets in the pattern circle – only a few more pellets than the 11⁄4-ounce load. The heavy load’s velocity was an impressive 1,295 fps.

I loaded one box of 20-gauge shells with a minimum charge of 15.5 grains of W-572, and another box with a maximum 18.8-grain charge and a 7⁄8-ounce charge of 71⁄2 shot in preparation for the opening weekend of grouse season last fall. I handed my wife a few shells of each load when we arrived at a ridgetop to start hunting blue grouse – purposely neglecting to tell Gail she had a mix of loads in her vest pocket before she headed up a ridge. I filled my pocket and Beretta 391 with the 20-gauge

Gail shot a blue grouse along a spring grown up in alders, then another on a dry, southern face of a ridge. We both got some shooting that day.

On the drive home, I asked if Gail had noticed any difference in the recoil of the loads she had shot and told her of my sleight of hand, giving her two different 20-gauge loads. “No,” she replied. “I might have noticed shooting clay pigeons,” she said, “but not when hunting.”