Practical Handloading

Long Range Shooting Part I: Cartridge Selection Factors

column By: Rick Jamison | October, 17

Shooting at long distances is becoming more popular in both competition and hunting. Shooters have heard about long shots made in the military and want to see how hard it is to make similar shots on paper or steel gongs with their own rifles. Hunters want to take game at even greater distances. Whatever the reason, shooters are finding out how much fun it is to shoot targets way out there.

It doesn’t take a big .50 BMG to shoot at long range. Jim Richards fired a 2.69-inch, five-shot group in competition at 1,000 yards using the diminutive 6mm Dasher, a cartridge based on the 6mm BR case. These shots and competition records show us what is possible. While most of us will not become registered competitors, nor will we shoot at 2 miles, we can still get in on the target-shooting fun with our hunting rifles and increase our game-taking distance.

I will not go into the ethics of taking game at long range, except to say that for me, shot placement is the key to making a clean kill. I do not seek out long shots, but sometimes it is the only way to take a specific trophy. I believe that a shooter should practice enough to know when he is capable of making a shot at a given distance, with a specific rest and under the shooting conditions at hand, regardless of the range. Otherwise, he should not take the shot. Bad shots can be made at 50 yards.

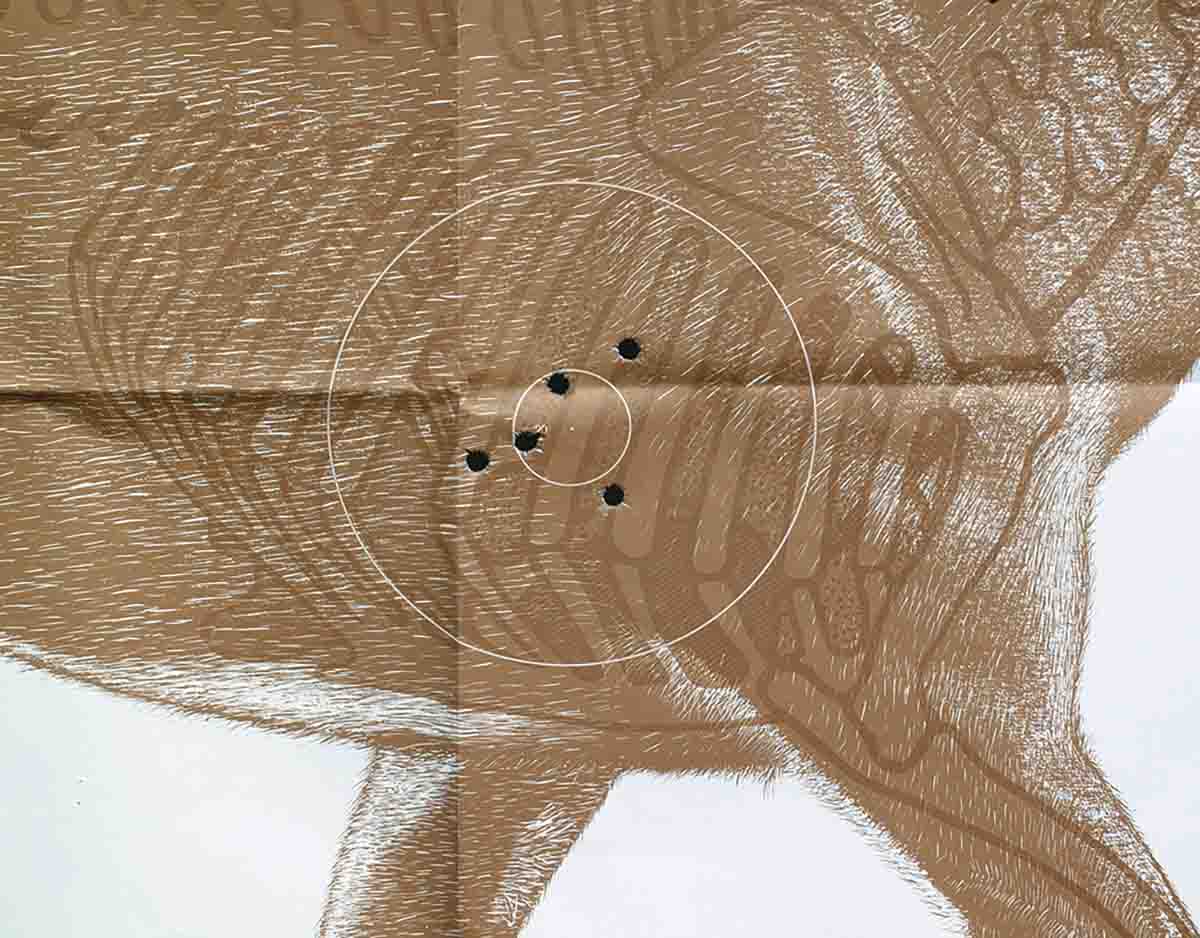

Paper targets are a good way to get a dead-on zeroed at multiple distances, and then steel gongs are fun and you do not have to continually go downrange. Practice is required to make first-shot hits consistently at distances beyond 400 or 500 yards. Equipment alone will not do it.

Manufacturers encourage this growth of interest in precision shooting at long distance by offering products for specific tasks. Some of the new propellants are not as temperature sensitive, and hence produce more uniform velocities. Bullet makers are producing longer, more streamlined hunting bullets that carry velocity and energy even farther downrange and perform at lower-impact velocities. Rifle companies offer specialty long-range rifles among their standard lines, and scopes are available with target turrets, long-range reticles and a choice of markings in inches or MOA. If serious about this type of shooting, you will probably end up purchasing a new rifle, scope and cartridges that lend themselves to long-range accuracy.

So what does it take in the way of a cartridge? Some shooters automatically think of big cartridges when considering “long range.” However, today’s competition shooters show us that big cartridges are not necessary to make precise hits, even at 1,000 yards (witness the 6mm Dasher record). In fact, people can shoot smaller cartridges with greater accuracy. A smaller cartridge with less recoil and blast is less likely to induce a flinch, and this makes shooting more fun. The more you shoot, the better you get, and smaller cartridges are less expensive to load, and less powder makes a barrel last longer.

Conversely, it is true that a higher muzzle velocity is an advantage, and it takes a certain amount of downrange bullet velocity and energy to take game cleanly. So how does one determine when a cartridge is enough but not too much?

For many years, 1,000 foot-pounds (ft-lbs) of energy has been something of an arbitrary minimum energy standard for a deer cartridge, and 1,500 ft-lbs has been considered necessary for elk at the point of impact. These figures are for all-around hunting, not long-range shooting. Based on my experience with modern bullets, I would be inclined to place the figures closer

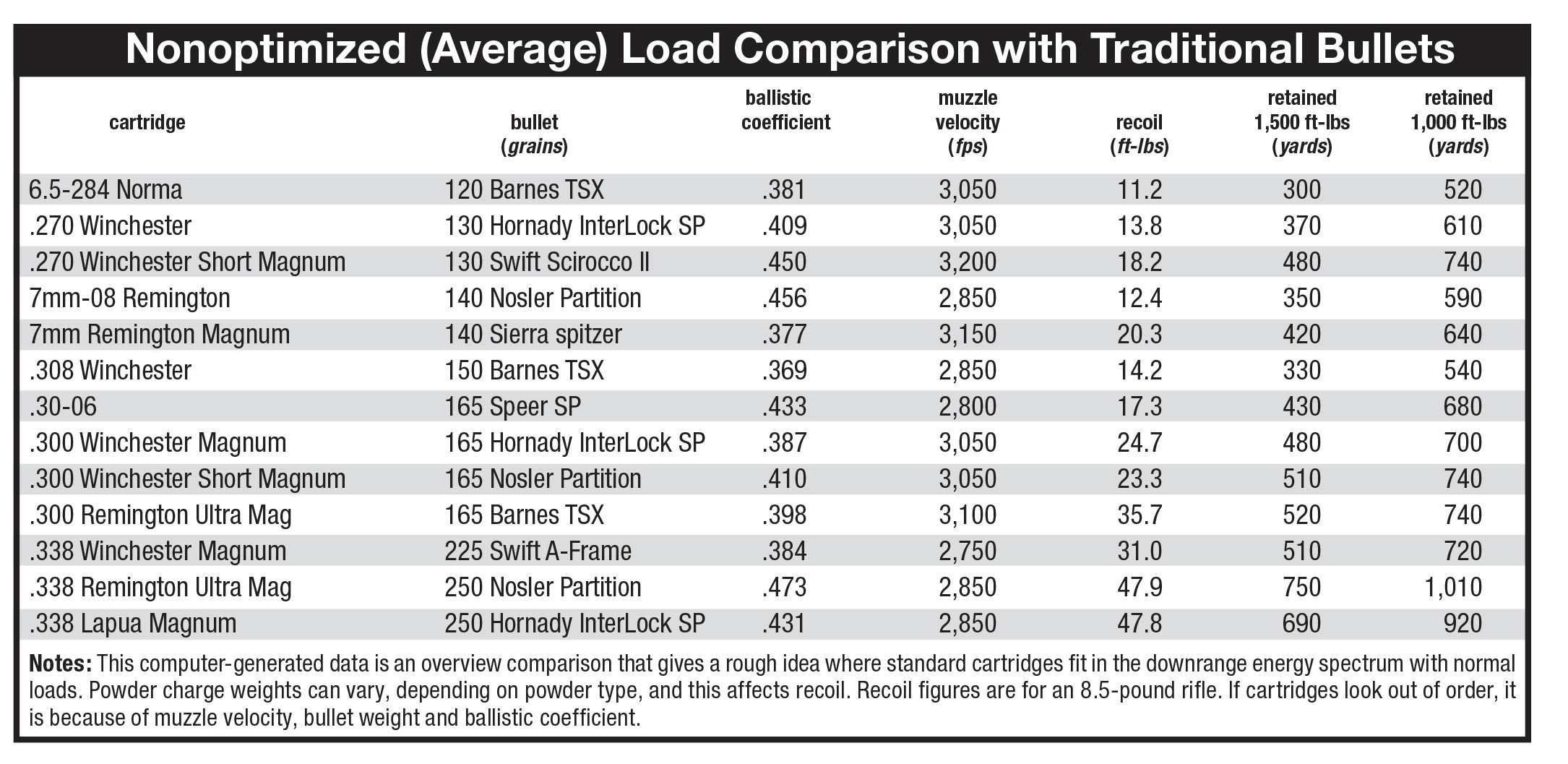

To be conservative, let’s stick with the old standards of 1,000 and 1,500 ft-lbs and see how a computer presents it. Software is not always the best source for practical ballistics, but it can be good for making comparisons. I use QuickLoad and its companion, QuickTarget, and sometimes Load From A Disk when at my desktop computer. For my smartphone I use iSnipe and BulletDrop+ quite a lot. If a .30-06 cartridge is loaded with a Hornady 165-grain spitzer flatbase bullet with a reported .387 ballistic coefficient (BC) to a muzzle velocity of

There is perhaps more involved with a specific load recipe than with the size and shape of the cartridge. Of course, impact velocity is important as well, insofar as bullet expansion is concerned. In the latter instance, the bullet would be traveling at about 1,434 fps at 930 yards. Will it expand and transfer killing energy at this low velocity without punching through with little tissue damage? That is yet another aspect of developing a long-range handload, and the subject will be covered in a subsequent column.