.30 Carbine

Loading for Revolvers and Carbines

feature By: Mike Venturino | February, 21

The final development of the M1 .30 Carbine is an interesting story of tests, failures, unimaginably fast development and incredible production numbers. Suffice it to say here, all initial submissions for the new .30 Carbine military arm were rejected. In late summer 1941, Winchester was unofficially urged to submit a test carbine. It won the competition and production plans began almost immediately, eventually being made by 10 companies. Between the first ones leaving the assembly lines in the summer of 1942 and war’s end in the summer of 1945, the 10 factories produced 6.25 million. So many existed, they were being handed out to troops like popcorn. They are shown in thousands of World War II photographs.

Although Winchester based the .30 Carbine case on its .32 WSL, it has remained an orphan in regard to “families” of cartridges. That is except for a few wildcats back in the 1960s spurred by the U.S. government dumping a quarter-million military surplus rifles through the DCM to NRA members. (My father wasn’t a gun guy or hunter, but he became an NRA member and purchased one of those DCM Carbines. It was my 16th birthday present in 1965.)

It’s doubtful if there were all that many .30 Carbine handloaders before those DCM rifles hit the market. Even then, there was U.S. military surplus ammunition floating about – otherwise I’d have had trouble feeding mine. Thinking back on it, to the best of my knowledge only Remington and Winchester offered commercial .30 Carbine ammunition in 1965. Remington’s offering carried 110- grain FMJs just the same as military loads, but Winchester had 110-grain JHPs. Saving nickels and dimes, I managed to buy one box of the Winchester loads. Even at that young age, I was familiar with the disparaging comments many World War II and Korean War veterans had about M1 .30 Carbines. The charge was they lacked “stopping power.”

Never did I handload for that first M1 .30 Carbine. In fact, later it was sold to raise money for a S&W K38 to use in local bullseye matches. That revolver was the firearm that introduced me to handloading. Not until 1980, when affluent enough to buy another M1 Carbine, moulds and dies, did I do my first handloading for this nifty little .30 caliber.

As a rimless case, .30 Carbine headspacing is by the case mouth as with 9mm Parabellum, .45 ACP, etc. Yet there must be some way to lock handloaded bullets in cases so they don’t get stuffed deeper during the violent shove from magazines to chambers in semiautos. This means a taper crimp must be applied. Here, I ran into a snag particular to the Ruger Blackhawk. My taper crimp die left too little of an edge at the case mouth. The Ruger’s hammer strike sometimes forced cases past the chambers’ headspacing edge. A solid whack or three on the ejector rod was needed to punch-out such rounds. At times, the Blackhawk’s hammer blow pushed cases forward to the extent that primers did not ignite. They just didn’t receive enough of a strike. However, all rounds that failed to fire in the Ruger worked flawlessly in my M1 .30 Carbines. My explanation for that is the carbines’ extractors assist in holding cases with such a meager case mouth edge.

From here on, .30 Carbine case preparation is fairly straight forward. Redding, Hornady and RCBS recommend the same shell holder as for .32 Auto. For the first two that’s No. 22. RCBS lists No. 17. Lyman’s No. 19 shell holder is listed only for .30 Carbine. Commercial cases have no crimped primers, and neither does U.S.-made military samples dating back to the 1940s. Here’s one bit of trivia; .30 Carbine was always loaded for the U.S. military with small rifle size, noncorrosive primers. And here is one caveat; don’t think that case mouths need not be belled and chamfered for jacketed bullets – they do.

Now a word or two about bullets; of course 110-grain roundnoses of .308 inch diameter are standard. However, FMJs are only good for plinking or perhaps ground squirrels. For any .30 Carbine rounds to be used on larger animals, JSPs or JHPs work well. A bullet that worked well in the Ruger Blackhawk was Hornady’s 90-grain JHP. However, it would not feed in any of my semiautos.

Naturally, I had to try cast bullets in M1 .30 Carbines and they have worked delightfully. Again, they are likely useful only for plinking or very small game. The first one tried back around 1980 was Lyman’s 311316. This was a 112-grain, flatnose gas check design. It functioned perfectly for whatever carbines I had on hand in those days. It also makes a fine small-game bullet for Ruger Blackhawks. It did not fare well in my AMT, due to failures to feed. Actually, nothing worked perfectly in that pistol, which is one reason I no longer have it. The other reason was muzzle blast. Despite its 7½-inch barrel, the noise level was likewise a reason for my Ruger .30 Carbine Blackhawk moving on to someone else.

Lyman no longer catalogs its 311316 bullet, but I still have my mould from long ago. To add more information to my .30 Carbine work, I found Redding/SAECO’s catalog listed a 120-grain roundnose, gas-checked design No. 302. One was ordered with my favorite number of cavities – three. For another option, Lyman’s bullet mould 311410 was ordered. It’s a semi-pointed, 130-grain plain base design.

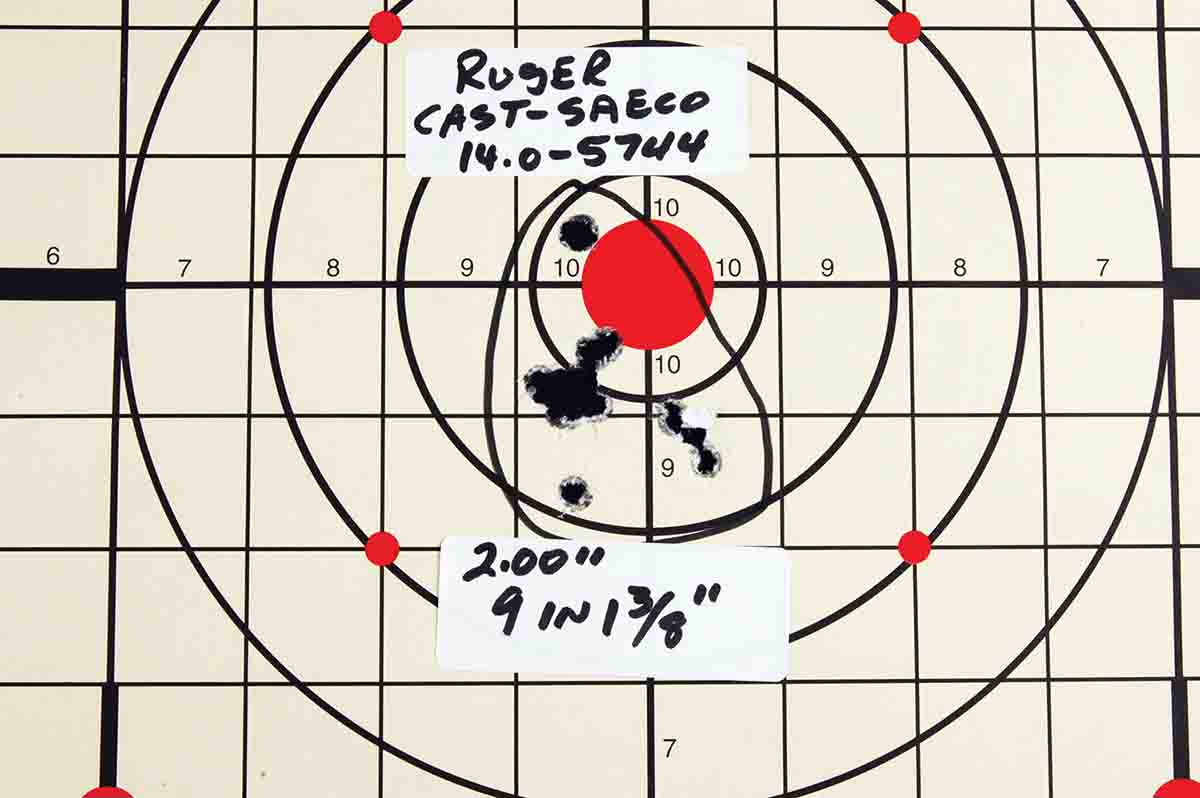

Anyone who handloads for magnum revolvers will likely have a propellant on hand suitable for .30 Carbine. Briefly stated, suitable choices run between Unique on the fast side and IMR-4227 on the slow end. Most of my early .30 Carbine shooting, circa 1980, was with 2400. More recently, I’ve used H-110 with either a Hornady or Sierra 110-grain JSP. Those are my favorite jacketed bullet combinations. With 115-grain Redding/SAECO cast bullets, I returned to one of my all-time favorite powders: Accurate 5744. Take note that .30 Carbine cases are formed for small rifle primers, which are slightly different in size to small pistol. Only the former should be used.

Coincidentally, charge weight is 14.0 grains for both A-5744 and H-110 with jacketed and cast bullets. The table will show exact chronograph results. Here’s an interesting fact. Initially, with jacketed 110-grain bullets 14.5 grains of H-110 was standard for me. It worked well in several M1 Carbines and both of my formerly-owned .30 Carbine handguns. However, upon acquiring a select-fire M2, problems arose. When fired in full-auto, extractors broke several times with jacketed bullet handloads, but the M2 would run all day with cast bullet loads and factory loads. A nearby gunsmith friend has the special tool needed to remove and reinstall carbine extractors. After three, he advised me to figure out the problem. Evidently, my M2’s chamber is a bit rough, and pressures from 14.5 grains of H-110 are a bit high. Backing off the powder charge to 14.0 grains of H-110 seemed to have resolved the issue – at least there haven’t been any more broken extractors.

As standard issue on M1 .30 Carbines, rear peep sights with blade fronts are normal. Most of my life they sufficed. For sure, M1 .30 carbines, whether wartime made or new reproductions, are not tackdrivers. My usual groups at 100 yards with iron sights run 3 to 4 MOA.

Of late, much of my .30 Carbine shooting has been done with M1/M1A1 reproductions from the new Inland Manufacturing Company. The one I came to favor is the “Jungle Carbine” with a 16-inch barrel and flared flash hider. Inland also can furnish a metal handguard with rail. I have fitted it with a 1.5-4x Leupold Scout Scope. This combination resulted in smaller groups and easy handling.

A few years back, during an especially bad Montana winter, a friend gave me a bag of new .30 Carbine primed cases and another bag of 110-grain FMJ bullets (maker unknown). They seemed like perfect plinking components for my M2. All were loaded the old-fashioned way, one step at a time. At the end, there were 1,003 cases and only 999 bullets. I called him up and said, “You owe me four more .30 Carbine bullets!” I thought that was funny – he didn’t.

.jpg)