Low velocity .22-250 Remington loads are great for called-in coyotes, and gentler to valuable coyote pelts. Accurate 5744 is a great powder for slower bullet velocities in many rifle cartridges.

The usual focus in handloading for a rifle is to get good accuracy at high velocity for the advantages the two provide at distance. However, not all shooting is at long distance, and you may have good reason to reduce a bullet’s velocity. Lower velocity is accomplished with a faster burning powder, and less of it. Less velocity and powder make for less recoil and less flinch-inducing blast. Less recoil and blast make for more pleasant shooting. More pleasant shooting results in more shooting, and more shooting improves marksmanship.

Hodgdon offers reduced load formulas for both of these propellants in many rifle cartridges. In a .22-250 Remington, Trail Boss works for very slow loads while H-4895 is for faster reduced loads. The two offer a very wide range of velocity options.

Cast bullets were the reason that I started using low velocity rifle loads nearly 60 years ago. Lyman has always been a good source of cast bullet data and many of the loads included shotgun and pistol propellants such as Red Dot, Hi-Skor 700-X, Green Dot, SR-4759, PB, and very quick burning rifle propellants like IMR-4198, IMR-3031 or Reloder 7. The people at Hodgdon say never use a powder slower burning than H-4895 for reduced loads. It can be dangerous. Also, you need to stay above about 1,000 fps or so to avoid getting a bullet stuck in a rifle barrel.

Lyman cast bullet loads produce all the advantages mentioned above. I used them back in the day when hearing protection for shooters was hardly available, and what I liked most was that the loads did not produce the ear-piercing blast of normal high velocity recipes. Low noise, low recoil loads offer a great way to get really good with your big-game rifle. I used them a lot in a .30-06 and .300 Winchester Magnum.

A .22-250 Remington coyote rifle later became a candidate for lower velocity. At the time, there were lots of jackrabbits in my region and it is a clear advantage to hear the large hares take off when they flush out of dry grass and brush. You can often hear their running foot beats as well. You cannot hear them with non-electronic muffs, nor can you hear them if you shoot high-velocity rounds without hearing protection because your ears are ringing so badly and hurting. Unlike in big-game hunting, pests or varmints can produce a lot of shooting.

Trail Boss (left) is shown for comparison alongside H-4895. The relatively large disks of Trail Boss also have large perforations. It makes for a very fluffy powder. Only 13.0 grains of it fills a .22-250 case to the base of a bullet.

It is faster and easier to buy a box of jacketed .224 bullets than it is to cast them. The solution for “low noise data” back then was to use cast bullet charges with jacketed bullets of the same weight. The results are similar, velocity-wise. Shooting 9.5 grains of 700-X behind a 45-grain bullet in a .22-250 doesn’t make a lot of noise, at least not like a full velocity load. You can imagine what “recoil” is like. I found that the Sierra 45-grain spitzers at 2,350 fps can really flatten a jackrabbit, fox or coyote.

What’s more, coyote fur prices were elevated back in the late 1970s, as they are today. I found that the lightweight 45-grain Sierras at the above mentioned velocity often do not exit but are retained under the hide on the offside. Rather than disintegrating as varmint bullets do at maximum .22-250 velocity, the bullets expand beautifully, producing classic mushrooms just like a big-game bullet should. This was a surprise to me at the time. In addition, the reduced velocity is a lot gentler on fragile fox pelts.

These .30-caliber bullets were fired from a .30-06 rifle. The bullet at left, shown unfired and expanded, is a Speer 110-grain spire point. The expanded bullet impacted wet newspaper at 2,175 fps. The bullet at right is a Speer 180-grain spitzer. The expanded bullet impacted at 2,038 fps. When comparing with the .22-250 expansion velocity, it becomes clear there is no set bullet speed that provides minimal expansion among all calibers and bullets.

Energy is not an issue with coyotes; all practical loads have more than enough. The important thing is energy transfer to the target, i.e. expansion. Too much energy only produces greater damage. Bullet weight is also a negative attribute for this application. A heavy bullet not only carries more energy, it penetrates more and is more likely to exit.

Young jackrabbits are a lot like cottontails for eating. They are not quite as tender but they are palatable, nothing like the boot-tough mature ones. This newly discovered recipe was a great improvement in reduced pelt and meat destruction.

One problem with those cast bullet recipes with ultra-quick shotgun and pistol propellants is there is plenty of space in a case for double-charging, so be careful not to do that. With today’s powders and loads, a handloader can avoid that situation by picking the right powder.

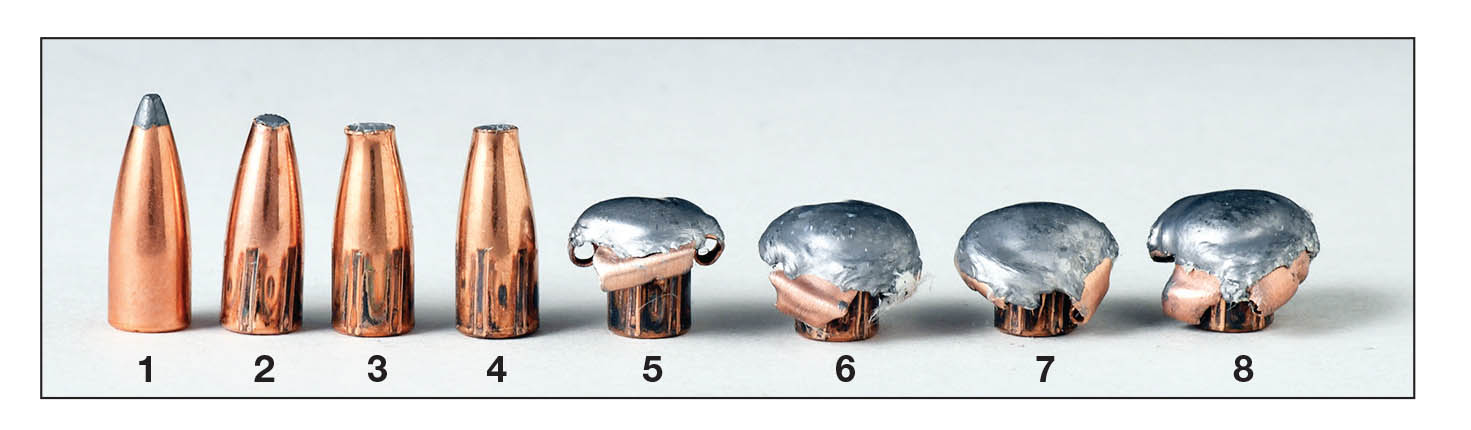

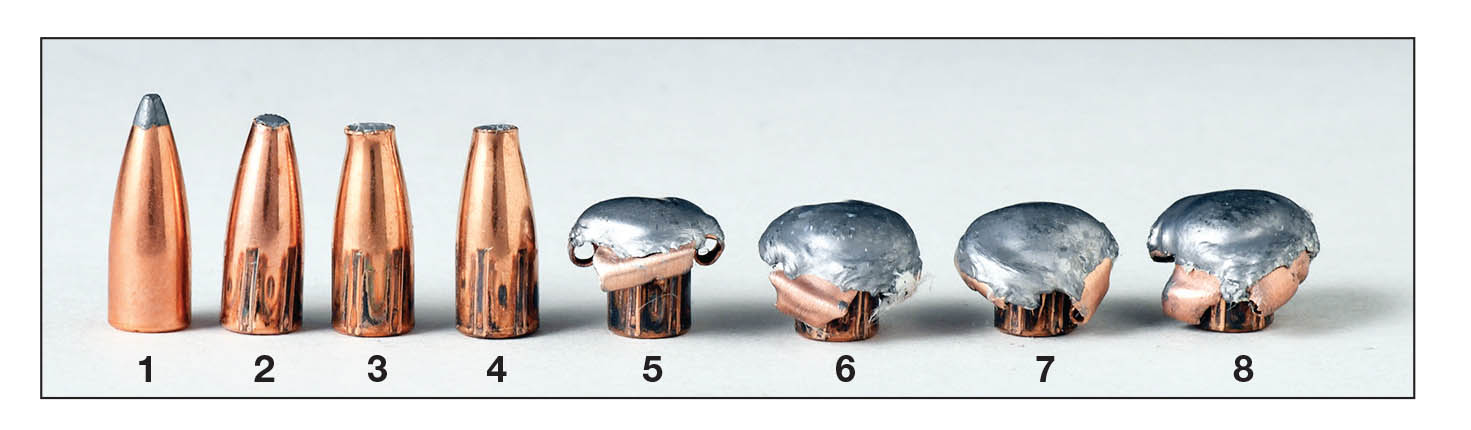

These bullets illustrate the type of expansion from a Sierra 45-grain high velocity spitzer at various impact velocities: (1) an unfired bullet, (2) a bullet with an impact velocity of 2,093 fps, (3) 2,154 fps, (4) 2,252 fps, (5) 2,310 fps, (6) 2,351 fps, (7) 2,464 fps and (8) 2,539 fps. The expansion difference between 2,252 fps and 2,310 fps is dramatic but consistent.

Today, Hodgdon provides reduced load data for jacketed bullets on its website, with formulas that can be applied to most cartridges for H-4895 (loads for which H-4895 data is already listed) and IMR Trail Boss. Trail Boss is light and fluffy with relatively large diameter and perforated flakes. It only takes 13.0 grains of Trail Boss to completely fill my .22-250 cases to the base of a 45-grain bullet. The Hodgdon data has specific Trail Boss .22-250 loads for a 55-grain bullet producing a reported 1,664 fps to 1,984 fps in a 24-inch barrel. Its H-4895 formula produces velocities from 2,316 fps (chronographed in my 24-inch barrel) to a high velocity maximum of about 3,900 fps. That is a lot of versatility available to handloaders only! You can use Trail Boss for greatly-reduced velocity and H-4895 for “faster reduced” velocities. There is not space to include Hodgdon’s formula explanations here. They can be found on the company’s website. While the formulas are simple, read them closely and pay attention. The basics are entirely different for the two powders.

These are the bullets and cartridges used in the expansion testing (from left): a .22-250 Remington with the Sierra 45-grain high velocity spitzer, a .30-06 with a Speer 110-grain spire point and a .30-06 case with a Speer 180-grain spitzer.

Besides Hodgdon, Lyman continues to turn out reduced load data for jacketed bullets, in some instances, as well as for cast bullets. Speer publishes some reduced-load jacketed bullet data and you can get current Speer data on its website. In all, there is no lack of tested reduced load data.

I have recently had requests for reduced velocity data for coyote calling. Not only do reduced loads save pelts, I suspect that the low noise results in higher success rates of second and third coyotes being called at a given stand.

Normally, a pound of powder does not come close to filling a standard one-pound container. Not so with Trail Boss; it appears that the size of the container for all powders was determined by this propellant.

So what velocity range, for example, is best for the short-distance shooting of called-in coyotes to minimize pelt damage? Coyotes are tough, and a bullet pass-through without expansion does not produce the instant demise desired by shooters.

To determine a minimum impact velocity for reliable expansion, I shot into water-soaked newspapers using the 45-grain Sierras. I placed the chronograph close to the newspapers to determine impact velocity, not muzzle velocity.

Using Accurate 5744 propellant in a Ruger .22-250 with a 24-inch barrel, I loaded it in increasing powder charge increments and recorded velocities. The test indicated that about 2,300 fps was the minimum velocity necessary for reliable expansion, and this velocity was consistent as indicated by multiple shots.

The next step was to determine a maximum shooting distance. Nearly all coyotes I have called were taken at less than 50 yards. Most were closer to 30 yards. However, I chose 100 yards as a maximum distance to retain the minimum velocity necessary for reliable bullet expansion. The Sierra’s low velocity ballistic coefficient combined with an already low starting velocity meant that the lightweight bullets slow down fast. In round figures, in order to have about 2,300 fps impact velocity at 100 yards, the muzzle velocity needs to be about 2,700 fps with this bullet. You can do that with Hodgdon’s H-4895 formula. Lyman data encompasses this muzzle velocity with its IMR SR-4759 or A-5744 loads. Loading 19.5 grains of my very old lot of A-5744 (Accurate Arms in Tennessee) does it in my Ruger rifle.

The .224-inch bullet diameter is far and away the most popular for coyote pelt hunting. If you are shooting a .222 Remington, some of the conventional starting loads with this round (Lyman) will also get into this velocity range with a 45-grain bullet, but most shooters today are using a .223 or .22-250, if not a Swift or even WSSM. Give the low-noise loads a try. My bet is you will get hooked.

.jpg)