Handloading Harder, Denser Shot

The Evolution of Tungsten Shot

feature By: John Barsness | February, 21

The first and still primary substitute was steel. The grade used in shotshells weighs about one third less than typical lead shot, which makes steel shot less efficient when traveling through the air. Essentially, it has a lower “ballistic coefficient” than lead shot of the same size. Steel shot is so much harder than lead it patterns well in more open chokes than many water-fowlers traditionally used – and can actually damage tighter chokes, or even cause barrels on doubles to separate near the muzzles.

Many waterfowlers initially reported steel wounded too many birds, but some hunters used shot sizes based on their experience with lead. Experimentation proved steel could work pretty well when using one or two sizes larger, especially when started at higher muzzle velocities. Steel shot also took up more room inside a shotshell, the reason 10-gauge shotguns made a comeback after decades of declining use, and Federal introduced the 3½-inch 12-gauge case.

In 1996, Federal invited me to take part in a preproduction test of its Tungsten-Iron shot in Argentina, thanks in part to the late Bob Brister, one of the best American shotgunners and writers of his generation. (His book Shotgunning, The Art and Science remains in print, 44 years after appearing in 1976, partly because of its detailed analysis of how birdshot patterns on moving targets, accomplished by Bob shooting at a long board on top of a trailer towed by the family car driven by his wife Sandy.)

Along with Grits Gresham, several writers gathered in Minnesota before flying south, touring the Federal factory in Anoka and getting a rundown on the new shot from the company’s head ballistician, whose background was in rifles, not shotguns. The 12-gauge ammunition that had already been shipped to South America featured 2¾-inch cases loaded with an ounce of No. 2 Tungsten-Iron shot, because he believed kinetic energy to be the primary factor in “projectile lethality.”

Down there, ducks and geese are often considered agricultural pests, so bag limits were very high and we shot a bunch of birds. The ammunition worked fine out to medium range, but at longer ranges the pattern became too thin for consistent results.

Part of the reason for using No. 2 Tungsten-Iron involved problems forming smaller shot sizes. Due to our results, Federal worked on the problem, and a couple of years later introduced ammunition with No. 4 and No. 6 shot, including 3-inch 12-gauge shells holding 13⁄8 ounces of shot. They sent me samples for field-testing, along with Tungsten-Polymer ammunition for older fixed-choke guns.

Other companies developed variations on the tungsten theme, and Eileen and I started testing them as well, partly by hunting waterfowl every few years with Ameri-Cana Outfitters in Alberta, Canada, at its Battle River lodge about 500 miles north of our Montana home.

The lodge is in the middle of the “aspen parkland” transition zone, between the southern prairie and the spruce/birch forest 100 miles farther north. Stands of aspen (birch) trees started appearing in the middle of grain and bean fields, so waterfowlers use portable blinds made of aspen saplings woven into wire fencing.

On one of our recent trips, birds poured into the decoys. Half an hour later Nick looked at us and said, smiling, “You are not shooting steel, are you?” This was not a question. While steel shotshells had improved considerably, he could still tell the difference.

We found ducks and geese crumpled at longer ranges when various kinds of hard tungsten-based shot in sizes No. 4 and No. 6. Of course, some geese were snows, lesser Canadas and “specklebellies” (white-fronted geese), weighing 5 to 8 pounds, but many were greater Canadas weighing over 10 pounds. Most fell dead, but a convincing demonstration took place when one big Canada got up after falling, and started walking off. By the time we noticed, due to being busy taking other geese from a pair of Labradors, the goose had waddled well beyond even long wingshooting range. I pointed my 12-gauge at its head and fired a load of No. 4 Tungsten-Iron. The goose crumpled, and I counted 90 long steps to where it fell.

Tungsten shot sizes continued to shrink over the next decade as technology improved, and some hunters started using even smaller shot on big birds like geese and turkeys. My personal experience is that tungsten shot can get too small for the biggest birds, sometimes failing to penetrate sufficiently despite pattern density, but hard tungsten does indeed require hunters to adjust their notions of shot size downward. These days I consider No. 4 tungsten shot a rather specialized load for longer-range waterfowling. At typical decoy ranges, smaller sizes work fine, even on greater Canadas.

Ballistic Products Inc. of Minnesota sells an incredible array of shotgun stuff, including shot and other handloading components. The company has its own piezoelectronic pressure testing laboratory, because shotshell “recipes” must be followed closely. Even the newest shotguns cannot take nearly as much pressure as modern centerfire handguns and rifles, the reason the stoutest shotshells average well under 15,000 PSI. Switching primers can cause pressures to vary as much as 2,000 PSI, and too-low pressures can also be a danger, due to the possibility of wads sticking in bores, an alternative way to create too-high pressures.

Right now, Ballistic Products has more than 6,000 pressure-tested handloads in 16 books and 50 brochures, including plenty for nontoxic shot, including steel, bismuth and several varieties of both soft and hard tungsten. The number of tungsten loads kept increasing while I worked on this article, due to Ballistic Products adding new variations of tungsten shot. President Grant Fackler sent me three kinds to test, tin-plated No. 4 BPX Devastator, plus two densities of No. 7 SpheroTungsten made by mixing, plus other components for loads in 20 and 12 gauge.

Shot density is expressed in grams per cubic centimeter (gm/cc). Typical “chilled” lead shot, for instance, is rated at 11.35 gm/cc. The densities of No. 7 SpheroTungsten are 15 and 18: Each pellet of 15 weighs about 1.3 times as much as a standard lead No. 7, and the 18 weighs about 1.6 times as much, due to being almost pure tungsten mixed with a very small amount of iron, copper and nickel.

The same principles apply to other shot, including tungsten, the reason tin-plated BPX shot travels slickly through the barrel and feathers compared to bare tungsten, even though overall density is only a little more than chilled shot. The bare, polished Sphero-Tungsten No. 7 shot, however, results in a denser pattern, and even without a coating flows relatively easily through the bore and choke due to its smaller size.

I acquired considerable experience with No. 7 lead shot 20 years ago while spending an entire Montana upland season hunting with the 28 gauge and using a variety of factory ammunition and handloads. In general, typical shooting ranges and the size of birds and feather density increase during the season, and my plan was to keep hunting with the 28 gauge until it proved too small. It never did, even on pheasants or sage grouse.

Because tungsten is so hard, shotcups need to be at least as thick as those used for steel shot, to protect the bore. However, since tungsten is so much heavier, the same weight of shot takes up far less room inside the same shotcup. Consequently, part of the cup often needs to be filled with “filler wads,” to raise the shot charge enough for a correct crimp.

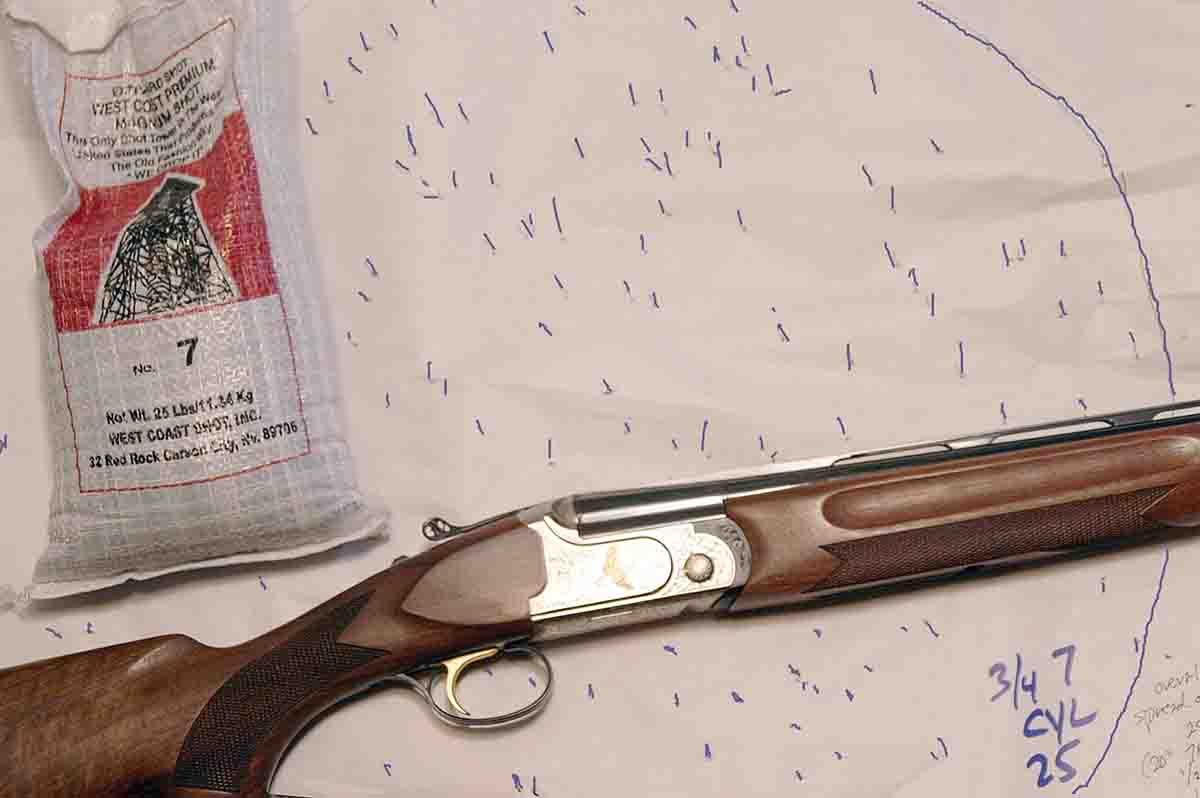

The components Fackler sent allowed me to construct loads for both the No. 7 and No. 4 tungsten shot in 2¾-inch 20- and 12-gauge shells. They all patterned very well, though the limited amount of shot did not allow shooting the 10-pattern strings some handloaders consider necessary for statistical purposes. However, enough testing was done to obtain a good idea of how all three kinds of shot perform.

The test guns were a pair of semiautomatic shotguns with screw-in chokes, Eileen’s 20-gauge Browning Gold and my Benelli Ethos 12 gauge. As expected, both patterned best with their improved-cylinder chokes, the 20 gauge’s providing a constriction of .012 inch and the 12 gauge .010 inch. All the patterns resulted in 67 to 86 percent of the shot charge landing inside the standard 30-inch circle at 40 yards, with an average of 77 precent, usually with dense centers.

The one time components were changed slightly from Ballistic Products data occurred with the two kinds of No. 7 shot in 12 gauge. I used the same components for 1¼-ounce loads with both SpheroTungsten 15 and 18, but had to use an overshot card on top of the 18 load for good crimps, due to the denser shot not taking up quite as much room inside the cup.

I also compared the penetration of the No. 4 BPX shot with some No. 4 high-antimony, copper-plated lead shot using a crude but effective test. I tend to collect all sorts of stuff to test penetration of both bullets and shot, and in the collection found an old phone book almost two inches thick, and shot the book with both loads at 25 yards. The copper-plated shot penetrated to page 307 and the tin-plated tungsten to page 359, a difference of 17 percent, even though the tin-plating reduced the density of the BPX closer to lead shot.

Of course, the big disadvantage of tungsten shot is cost. At the time of this writing, Ballistic Products’ website listed the No. 7 SpheroTungsten 18 on sale at $102.18 for a 2-pound jar. Doing the math results in $3.19 per 1-ounce charge. It also listed BPX Devastator at $66.84 per 2 pounds, $2.61 for a 1¼-ounce charge.

That is pricey, but aside from deeper penetration at longer ranges, tungsten shot also allows the use of lighter-recoiling shotguns on even big geese. In fact, tungsten shot allowed Eileen to continue goose hunting after developing recoil headaches around a dozen years ago. At the time, her waterfowl gun was an over/under 12 gauge. After that she switched to the 20-gauge gas autoloader, finding that with tungsten shot it killed even big Canada geese quite well.

I also like tungsten, mostly due to a lot of Montana pheasant hunting taking place near streams and irrigation ditches where waterfowl can be encountered. As a result, over the years some of my pheasants have been taken with both steel and bismuth shot, and while both worked within their limitations, the first bird I took with the SpheroTungsten was a rooster pheasant.

Early October set records for high temperatures and hunting was slow until a cold front rolled in. Lena the Labrador and I took an evening walk around a wheatfield where Canada geese often pass overhead, and pheasants lurk in the nearby cover. The closest flock of geese flew a little too high even for tungsten, but Lena flushed a rooster from a timbered shelterbelt next to the field. Luckily, I got off a quick, long shot, the bird crumpled in mid-air and Lena quickly found it in the tall grass. I suspect she likes tungsten too.

.jpg)