Cartridge Board

.22 Rimfire Shot Cartridge

column By: Gil Sengel | February, 21

Humankind has battled rats and mice since before recorded history. Not only are they repulsive little varmints, but they apparently dislike us as well because they have killed us by the millions!

Due to the fleas they carry and a propensity to eat almost anything, rats and mice are responsible for the transmission of terrible suffering. Examples include bubonic plague and New World smallpox. Outbreaks that killed only a few thousand people aren’t even noted in history. Any of those people would have gladly traded a cow and two pigs for a smoothbore .22 and an oxcart load of .22 rimfire shot cartridges.

Meanwhile, mankind invented hundreds of devices to kill rats and mice. All were quite labor intensive. Most folks just relied on instinct, picked up a club and squashed the little beasts. The only problem is that rats are quick and largely nocturnal. They also learn to avoid humans carrying long sticks. There had to be a better way.

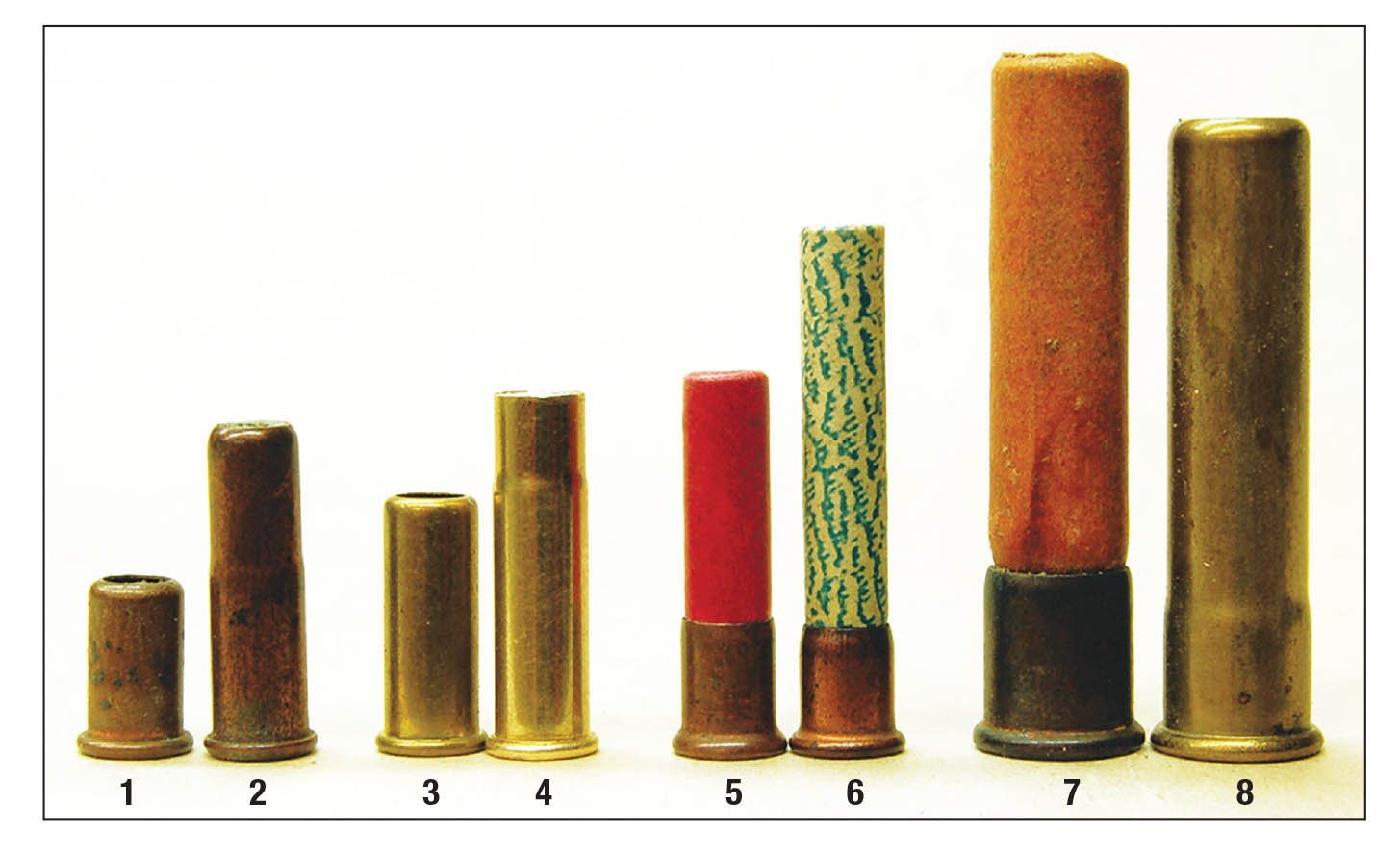

Development of the rimfire cartridge by Smith & Wesson resulted in the .22 Short by 1857. Loading the tiny case with shot was done, although just when is debatable. Black powder took up too much space, leaving little room for shot. Perhaps it worked for mice that were just out of club range.

Some references insist larger caliber centerfire shot cartridges came first. This would be in the 1878/80 period. Such is doubtful because these rounds contained far more shot than needed to kill a rat and were quite expensive.

I find it hard to believe that once the .22 Long case became available in 1871 that it was not immediately loaded with shot in the same manner as a brass shotshell. Black-powder, copper-cased rounds like this were disassembled years ago. They contained a pinch of powder similar to that found in firecrackers (Boys tend to take everything apart.) An over- powder wad then rested under about 18 grains of tiny misshapen shot. A thin over-shot wad held it in place. Some have argued that this is impossible because there would not be enough room for an adequate charge of black powder. This is not true. These little rounds only had an effective range of 10 or 12 feet, so a muzzle velocity of 650/750 feet per second (fps) would have been adequate. The rodents were in for a surprise.

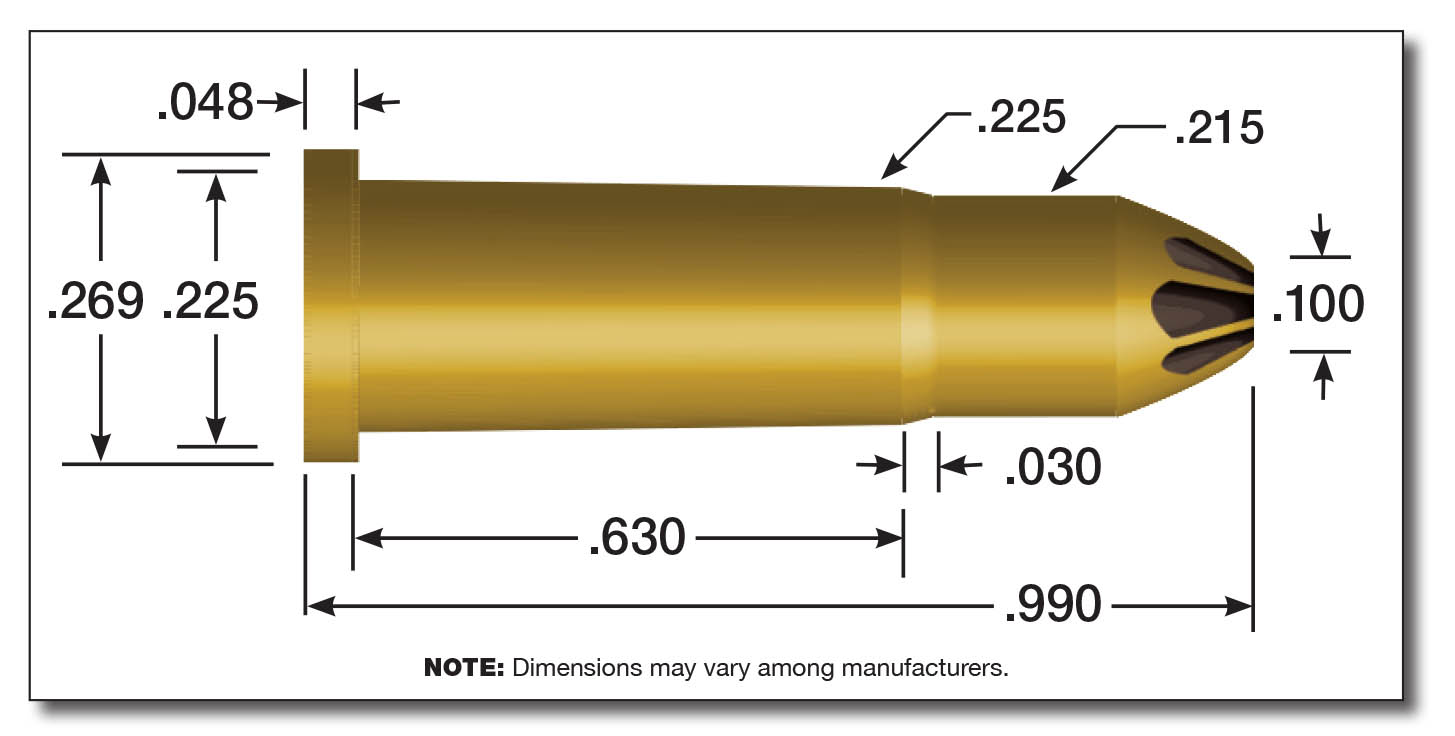

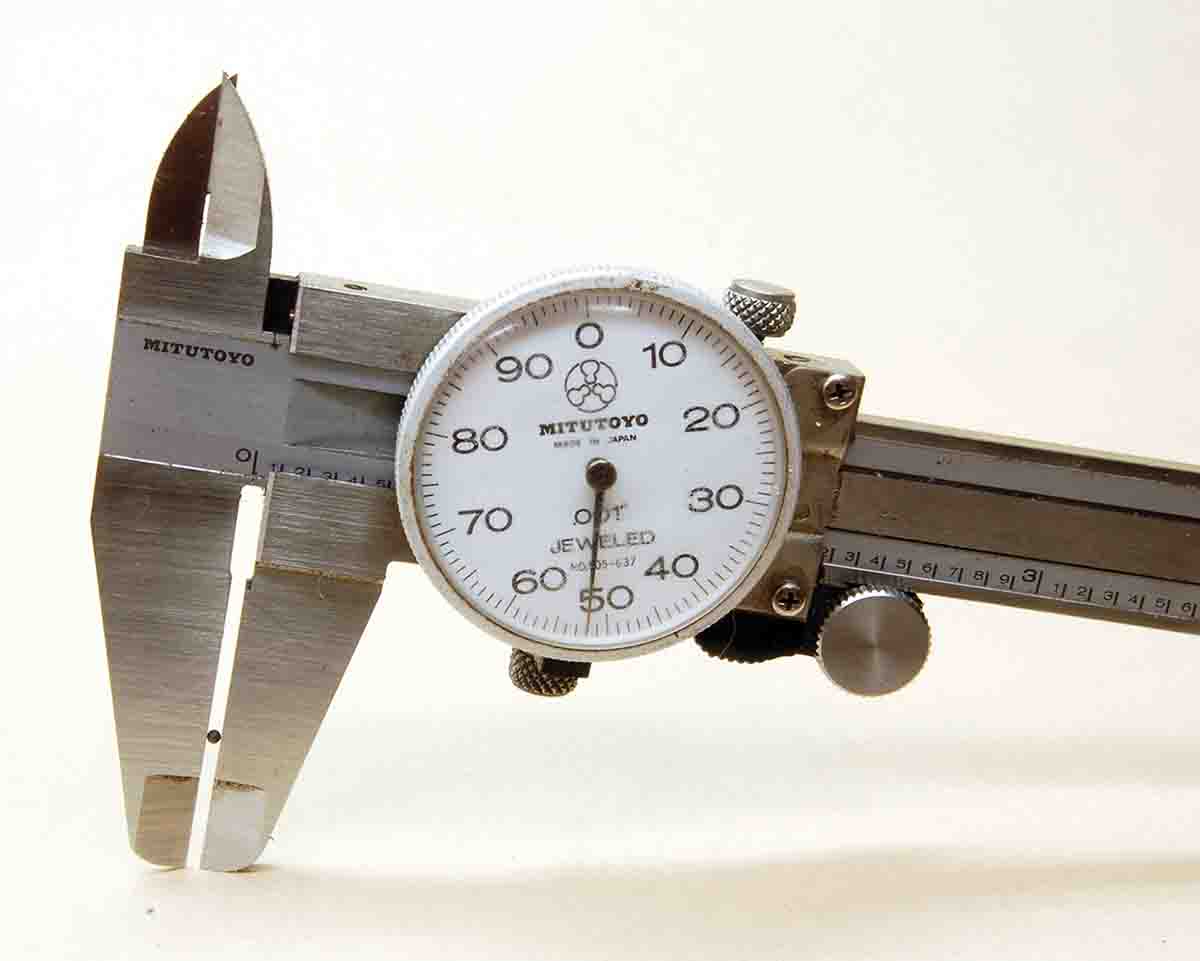

The .22 rimfire shot round was soon using smokeless powder in standard length cases with a top wad, “paper bullet” sabot and extended case. Yet it was the modern extended case .22 Long Rifle with no top wad and what is called a “rose crimp” or “folded crimp” that maximized its effectiveness. The round was cheap and fed through manually-operated repeaters. It became available from Winchester in 1934, containing 25 grains of No. 12 chilled shot. No muzzle velocity was given.

In Great Britain and on the continent, things were done differently. Kynoch does not appear to have loaded any .22 rimfire shot rounds and Eley only listed them in a long rifle case with topwad. What was loaded were tiny rimfire shotshells made with paper bodies and copper or brass bases. These were available in 5, 6, 7 and 9mm. It is impossible to judge performance as all are gone today, except the 9mm, which is much more powerful than the .22 rimfire.

By 1950, Winchester, Remington, Western and Peters all offered the extended-case, rose crimped .22 Long Rifle shot cartridge. Federal came on board about 1964. The Winchester and Federal brands are still available today. A relative newcomer here is CCI. A hard-blue plastic capsule shaped like a blunt-nosed bullet is seated in a standard long rifle case. Published data indicates 31 grains of No. 12 shot at 1,000 fps muzzle velocity. CCI also loads 52 grains of No. 12 shot in a similar blue plastic capsule, at the same velocity, in .22 WMR.

It is now logical to ask how a tiny shot cartridge that has changed little since the 1880s – and none since 1934 – can still be available today and not have been replaced or ruined by our tendency to “magnumize” everything. The answer is that a lot of it is still being fired, and personal experience indicates the reason why.

When growing up in the rural Midwest in the 1950s, my grandpa gave me an old single-shot .22 smoothbore. Big grasshoppers, dragonflies and bats were shot for fun. Mice and rats around the buildings were strictly business. There were no really big rats, only what we called “gray rats,” which were 5 or 6 inches long without the tail. These rodents just rolled over and twitched a few times as long as range didn’t exceed 15 feet or so. This is really quite a long distance when shooting around or in buildings. It is the “in buildings” part that is important. Hundreds of rodents were shot in buildings with dirt or wood floors and walls, with no damage from the shot. Also, I was never stung by ricocheting shot, even if floors were concrete. Apparently, the tiny shot loses energy very quickly – exactly what it was designed to do.

While what I did as a kid may not be considered normal, all cities and

towns have always had rat problems and pest control people to deal with them. Trapping isn’t a solution unless traps are checked daily because rotting rat carcasses are a worse health hazard than the rats themselves. Poisons are too random and there is still the problem of rotting carcasses. On the other hand, a rat popped with the little shot cartridge is controlled! This is the only shot cartridge that is a permanently possible explanation for the continuing availability of the little round. There is no need or want for more power or noise. It works perfectly.

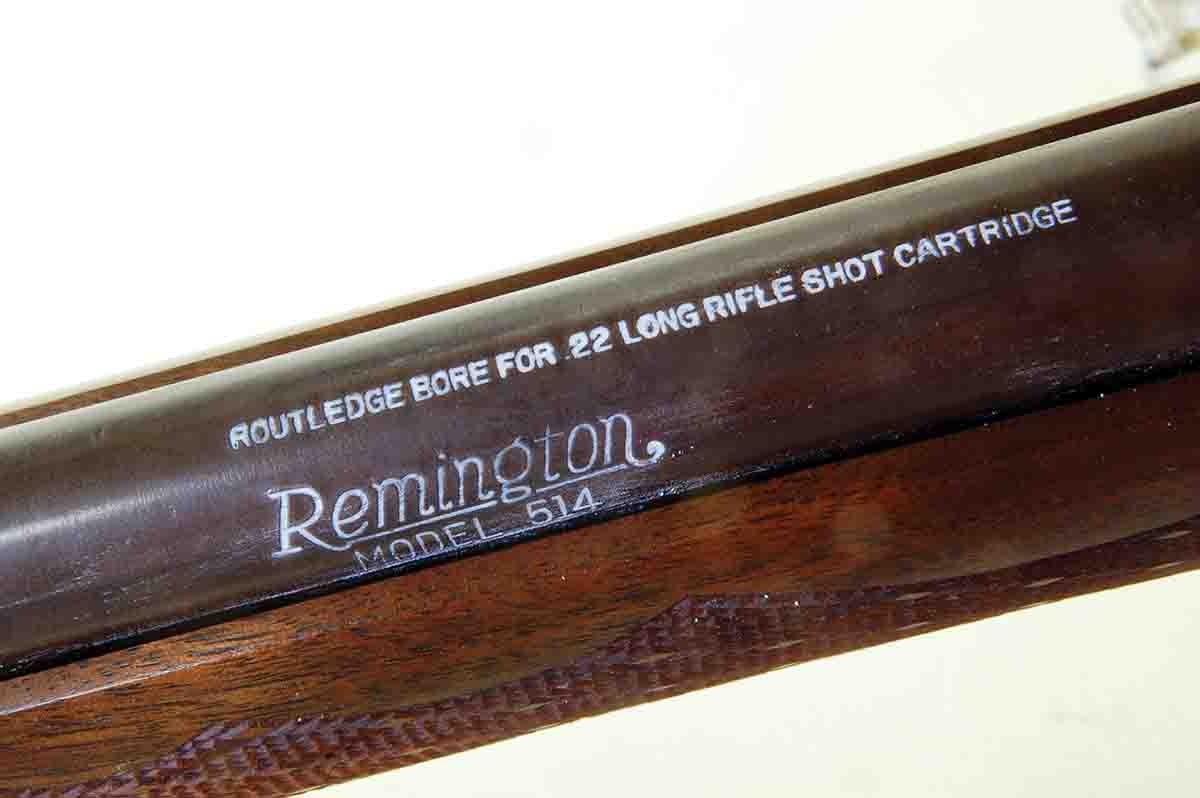

While most shot cartridges are probably fired in guns with rifled barrels, the two shown here are factory original smoothbores chambered for the .22 shot round. These were once offered by all makers of inexpensive rimfires. The Stevens Favorite was probably made about 1920. Note there are no rifle sights, just a shotgun bead at the muzzle. The bolt gun is a Remington Model 514 with what is called a Routledge bore. The barrel is .22 smoothbore for 12 inches, then opens to .400 inch for 12 inches. It was intended to produce much improved patterns for shooting tiny clay targets. It does just that!

All in all, the .22 rimfire shot cartridge is made and sold in great numbers, yet many shooters today don’t know it exists unless they have a need for it. Yes, it’s specialized, but it is one of the few uniquely useful rounds that is also a lot of fun. From bugs to bats and mice to rats, there is never a dull day with a .22 and a pocketful of shot cartridges.