Loading the .32 ACP

Not Easy, but Worth the Effort

feature By: Terry Wieland | February, 21

Yet W.H.B. Smith, one of the most respected handgun experts of the twentieth-century, dismissed it as a “thoroughly useless cartridge.” Even its admirers, and there are a few, tout its convenience, not its power or accuracy. In other words, John Browning’s little creation from 1900 is a bundle of contradictions.

The .32 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol) or, as it’s known in Europe, the 7.65mm Browning, was designed in 1899 and put into production in 1900 by FN in Belgium. The gun was Browning’s small hammerless semiauto, and it proved so popular that by 1912, FN had produced more than a million of them. In the U.S., Colt chambered it in the Browning-designed Model 1903, and from there it was adopted and manufactured almost everywhere. Other famous guns chambered for it include the Walther PP and PPK, various Beretta models, CZ in Czechia and a dozen Spanish companies.

The cartridge’s very ubiquity has led to some of the problems that have plagued it, and given handloaders fits since the beginning. There is disagreement over bore diameter, and hence bullet diameter, with White & Munhall (Pistol and Revolver Cartridges, 1967) listing bullet diameters ranging from .303 to .313 inch. For this reason alone, it is essential to start cautiously and work up, especially when working with an older pistol of unknown bore diameter.

The cartridge has been produced in a wide variety of bullet weights and types in a range of velocities, but factory ballistics are typically listed as a 71-grain full-metal-jacket, round-nosed bullet at a muzzle velocity of 960 feet per second.

One area of complete agreement is that, while the cartridge may not be “thoroughly useless,” it is marginal at best for self-defense, inadequate for hunting and not accurate enough for target work. In Cartridges of the World, Frank Barnes said it was adequate for nothing larger than cottontail rabbits or birds.

All of that does not mean it cannot be reloaded, or that the reloads cannot improve its performance substantially. Today, there are several bullets intended for the .32 ACP that make it a much more fearsome beast for use as a house gun, carry gun or deep-concealment backup.

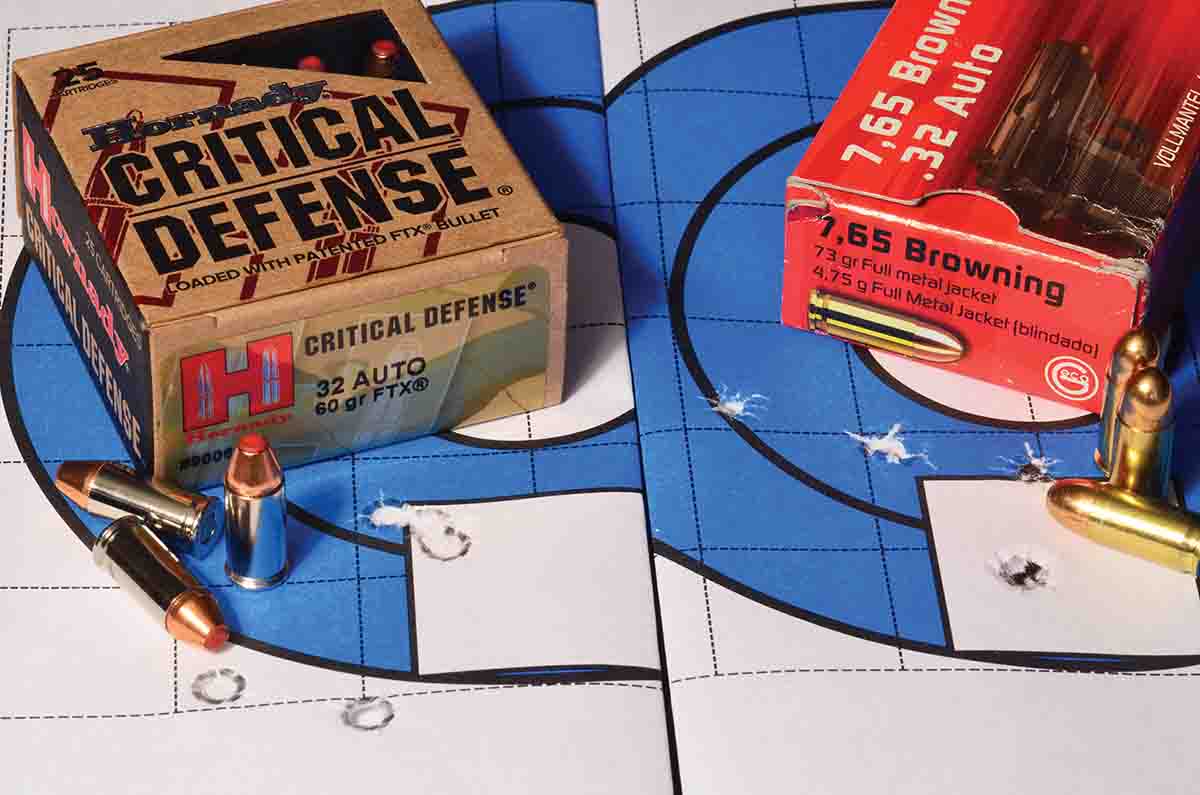

To the best of my knowledge, the first company to really try to improve .32 ACP performance for defense purposes was Cor®Bon. During a visit there in 2004, I shot some rounds loaded with Cor®bon’s expanding bullets which were both accurate and powerful, if felt recoil is anything to go by. Since then, handloaders have seen the advent of tactical bullets from Speer and Hornady, as well as a lengthening list of smaller, specialty bullet companies.

Most of these bullets are lighter and are either a radical design (such as Lehigh’s 50-grain Xtreme Cavitator) or depend on higher velocity to expand properly (Hornady’s 60-grain FTX). Since .32 barrel lengths vary from little more than an inch to 4 inches or more, the actual velocity delivered needs to be considered. The numbers listed in the manuals may not materialize with your pistol. Also, there is the pistol itself. For example, one well-known .32, Beretta’s tilt-barrel Bobcat, is notable for frames cracking. This is usually blamed on excessive pressures from overly ambitious handloads. Given the number of other older, sometimes questionable .32 ACP pistols around, handloaders should tread carefully.

My favorite .32 ACP is a Beretta Model 81, which looks like a scaled-down Model 92. It’s a stout little pistol that welcomes any ammunition I feed it, but I’m still cautious. It has a 33⁄4-inch barrel and was my test pistol for the loads listed here.

As a general rule, I like to load concealed-carry and car guns with factory ammunition, in this case, Hornady’s Critical Defense with a 60-grain FTX bullet. At the moment, with ammunition in short supply and component bullets equally scarce, the need to handload for the .32 is really to provide practice ammunition. When your ammunition supply unexpectedly dries up, it’s comforting to have the wherewithal to produce your own. It’s funny, too, how many friends you suddenly find you have when this happens.

One point to make early on is that while it’s possible to load the .32 ACP to greater velocity, and even sometimes to make ammunition that’s more accurate, the critical factor is how well it feeds, operates the pistol’s mechanism, ejects on cue, chambers another round and does it all without damaging anything.

Because the .32 ACP is such a small case, it’s a good idea to approach it with none of the usual expectations. It presents some difficulties all its own. For example, in a Handloader article in 1984, Ken Waters reported that the flash holes of Winchester brass were so small he could not decap them. I did not encounter that, but I did find some other anomalies. One was that some primer pockets were too snug, causing primers to be crushed rather than seated. It pays to go slowly and carefully, paying close attention to how the lever feels as the primer is seated. Waters also found that violent chambering and ejection often deformed the thin semi-rim to the point where it would not slip into the shell holder. Finally, the brass, being so tiny, it’s relatively fragile and case mouths can be folded over all too easily. Case mouths need to be checked, re-conditioned and belled slightly, even when using jacketed bullets, some of which are not chamfered at the base.

The whole loading operation, from beginning to end, is more delicate than most of us are accustomed to.

Typical powder charges for the .32 ACP run from 1.5 to 3.5 grains, but the case has such limited capacity that one or two tenths of a grain can boost pressures uncomfortably. Many powder measures don’t deliver consistently with such small amounts, so I acquired one of the new Redding Competition Model 10X-Pistol powder measures. It looks like the venerable Model 3 measure we know and love, but its micrometer and drum can deliver charges as small as one grain and I found that once it was set, it never varied.

When it comes to dies, I had a Redding three-die titanium carbide set, augmented by a Redding taper crimp die. Most .32 FMJ bullets have no crimping groove, so ensuring a tight fit for the bullet requires careful treatment.

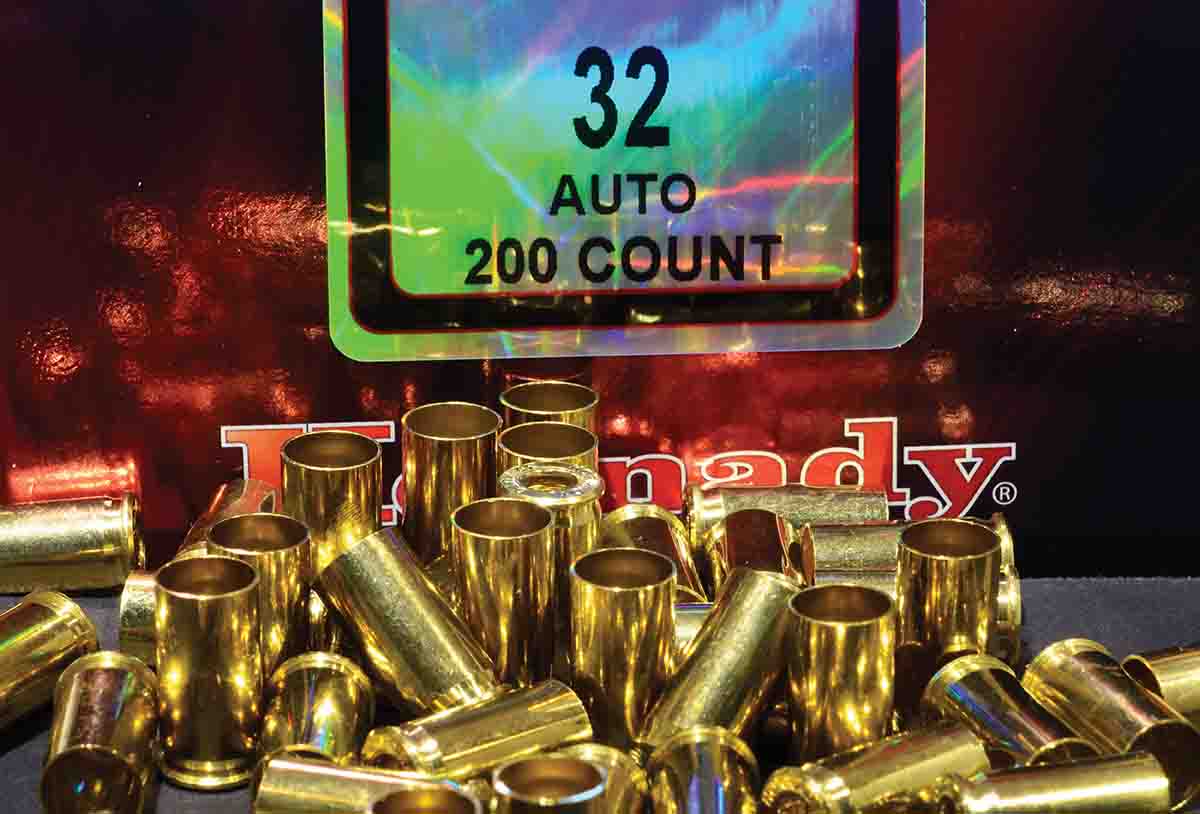

For this article, I obtained a good supply of new Hornady brass, and a backup supply of PPU (PrviPartizan) brass. The only 71-grain bullets I could find were Berry’s, which look jacketed but are actually plated cast bullets. I’ve always had good results with them, and this was no exception. I also had a supply of 68-grain cast roundnose bullets from an old Lyman mould 311227. I found some Lehigh Defense 50-grain Xtreme Cavitators at Graf & Sons, as well as some PPU 71-grain jacketed hollowpoints (JHP).

The Berry’s and cast bullets have no crimping groove, while the PPU and Lehigh bullets do. Because of problems with semiauto functioning, seating depth and a firm grip on the bullet are critical. The taper crimp die handled all of them perfectly.

One immediate problem cropped up: The PPU bullets are .308-inch in diameter, while the Berry’s are .312. Hornady brass measures .310 at the mouth, which means the PPU bullets could not be loaded readily, and required some fiddling with the dies. PPU brass accepted PPU bullets with no problem. This situation is far from unique with the venerable .32 ACP, and needs to be kept in mind at all times.

The accompanying load table tells the story, but a few comments are required.

In years past, Bullseye, Unique and Red Dot were the three standard powders for the .32. A moderate load of Bullseye gave no surprises, but Unique and Red Dot did. The loads listed in the table are the minimum starting loads in Lyman Reloading Handbook for Rifle, Pistol and Muzzle Loading, 45th Edition (1969), and the measured velocities were 180 and 130 fps higher than expected. Loads approaching the maximum were disturbingly high with much higher velocities. Having no way of measuring pressure, but expecting the worst, it was decided to eliminate the results from the table (so as not to encourage anyone) and include a caution that anyone working with Unique and Red Dot work their way up very, very cautiously. Anyway, there are modern powders that give better results.

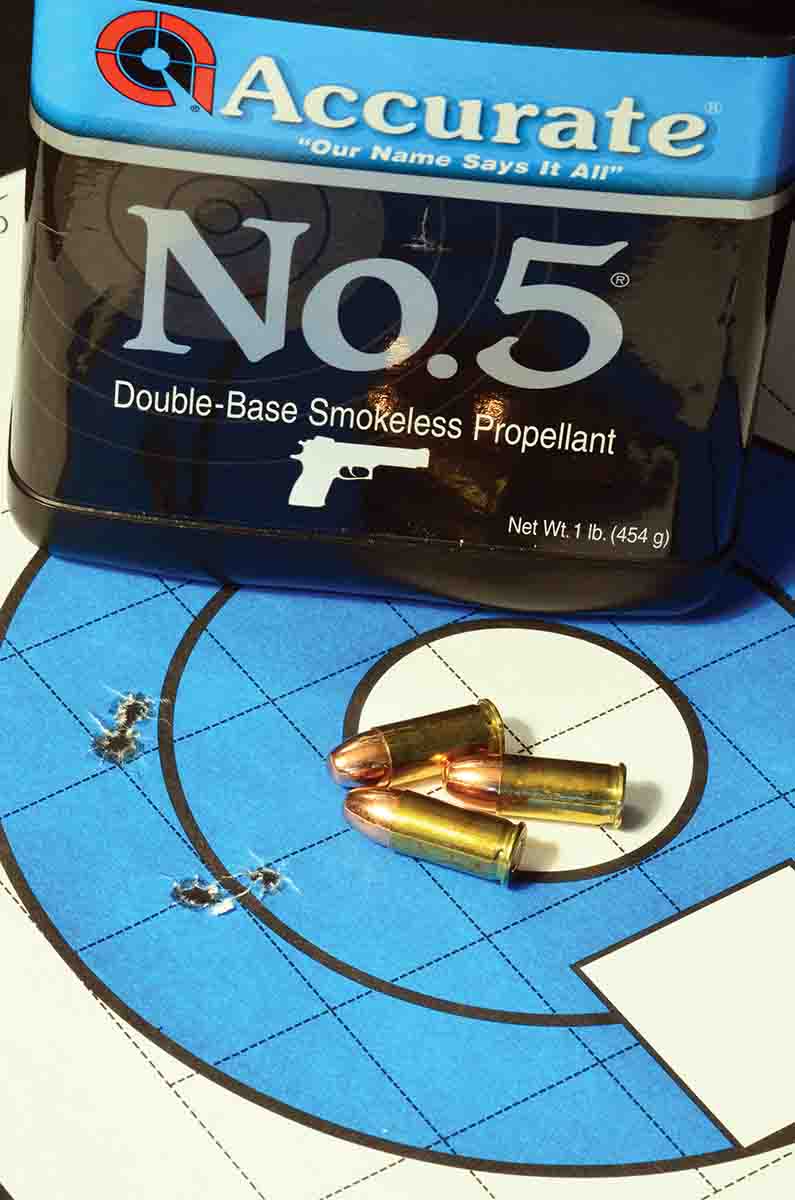

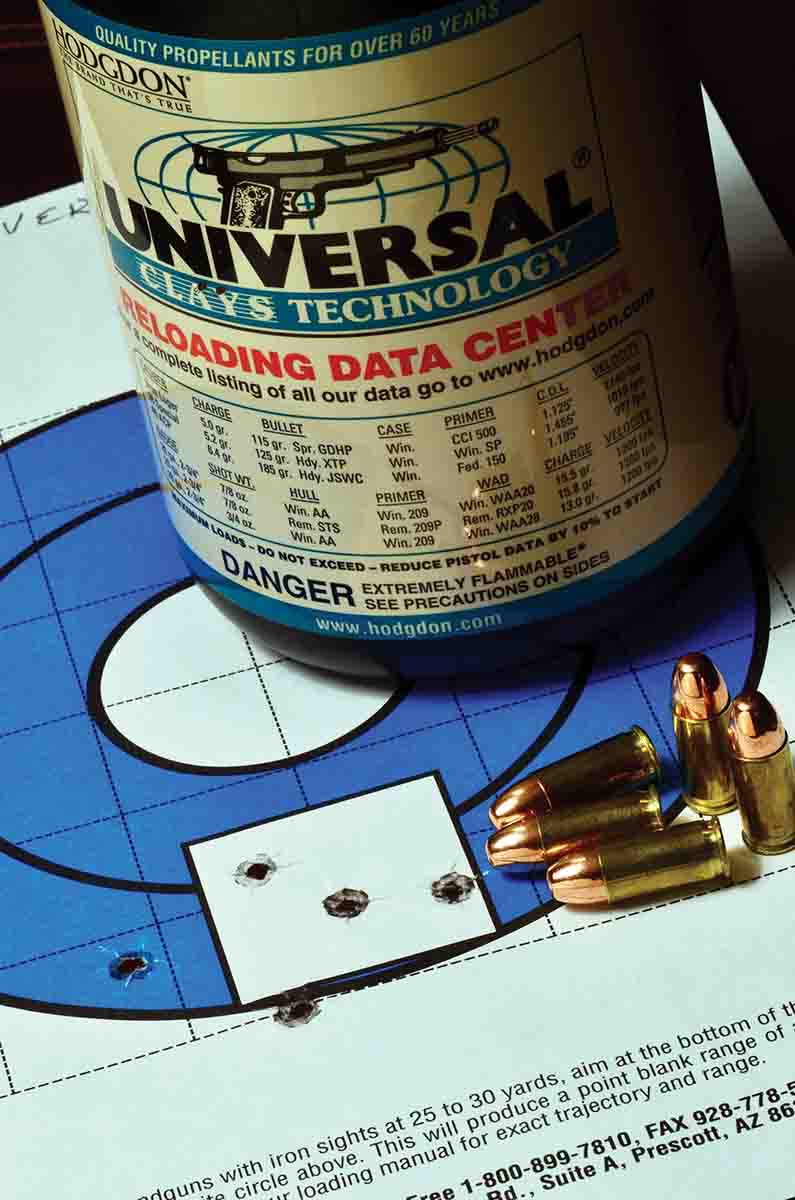

Bullseye was a disappointment, given its long use in this cartridge. Hodgdon Clays and Universal were both somewhat erratic with moderate velocity, while the two Accurate powders, No. 2 and No. 5, delivered higher velocity and were both consistent and accurate. Ramshot’s True Blue, behind the Lehigh bullet, worked like a charm.

As a control group, I test-fired two factory loads, GECO 73-grain FMJs and Hornady Critical Defense with the 60-grain FTX bullet. The handloads measured up very well.

A consideration that does not exist with most handguns is not just accuracy and where the group is in relation to point of aim. Most .32 ACP pistols have either fixed sights, or sights that can be adjusted only crudely at best. It’s better to have a moderately powerful and accurate (as to group size) load that puts its bullets near the point of aim than one that blasts the hinges off and prints groups the size of a quarter, but shoots 4 inches high and 6 inches left. Relentless experimenters may want to fiddle with sights, tapping them back and forth to accommodate whatever ammunition is being used, but I was looking for a practical solution that provided both defensive and practice ammunition that could be used without ever touching the sights or worrying about accommodating anomalies.

Having said that, the cast bullet load with IMR SR-7625 works best in my Beretta. The Lehigh Xtreme Cavitator load with True Blue is perfectly acceptable, and I would not hesitate to carry it as a defensive load. The best overall practice load with the Berry’s 71-grain bullet was 2.3 grains of Universal.

In spite of the loading problems mentioned above, one very gratifying thing about this whole affair is that, when I got to the range with all these different loads, they all worked flawlessly, something I really did not expect. Compared with handloading other semiauto cartridges, loading for the .32 ACP proved to be remarkably easy.

.jpg)