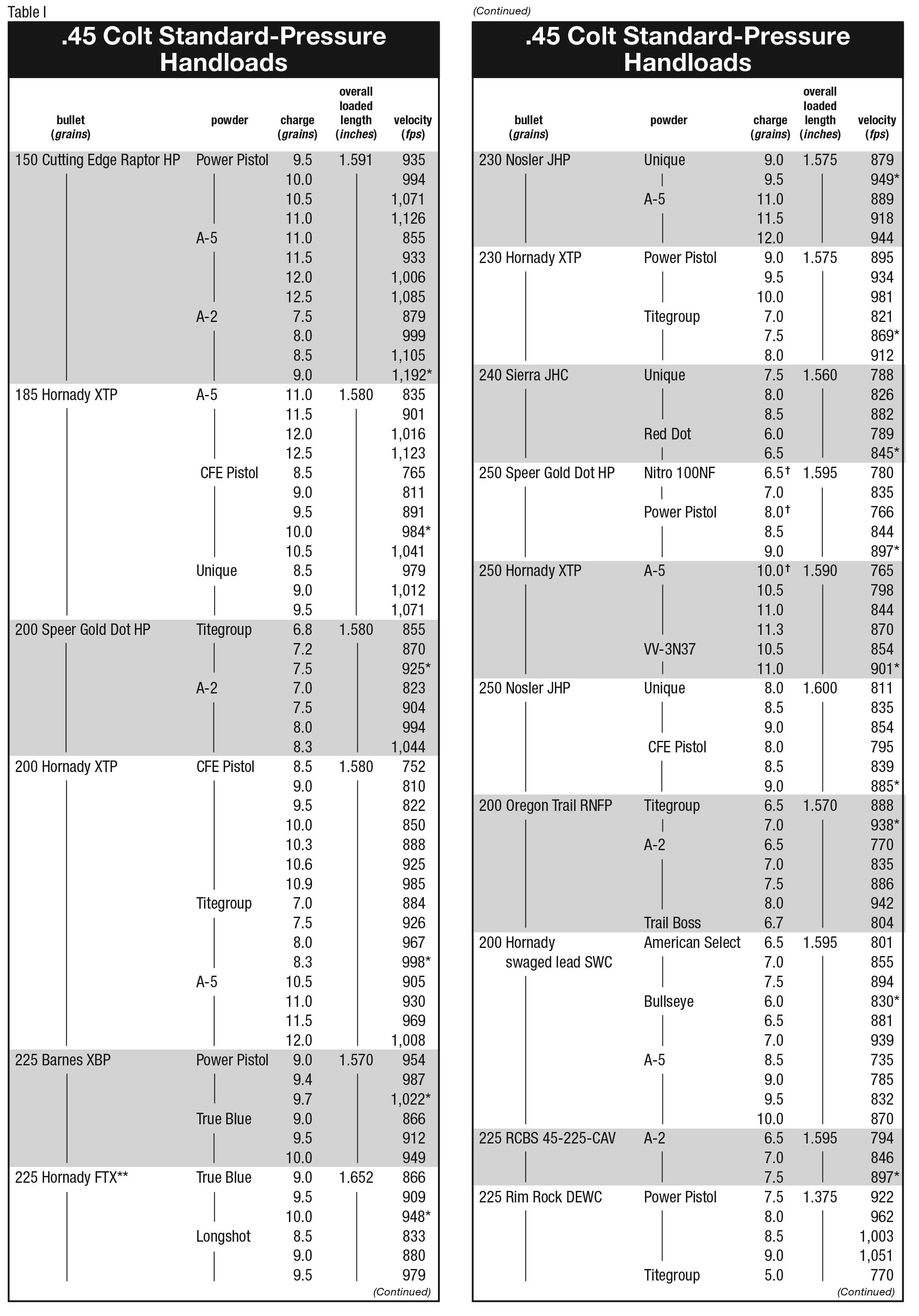

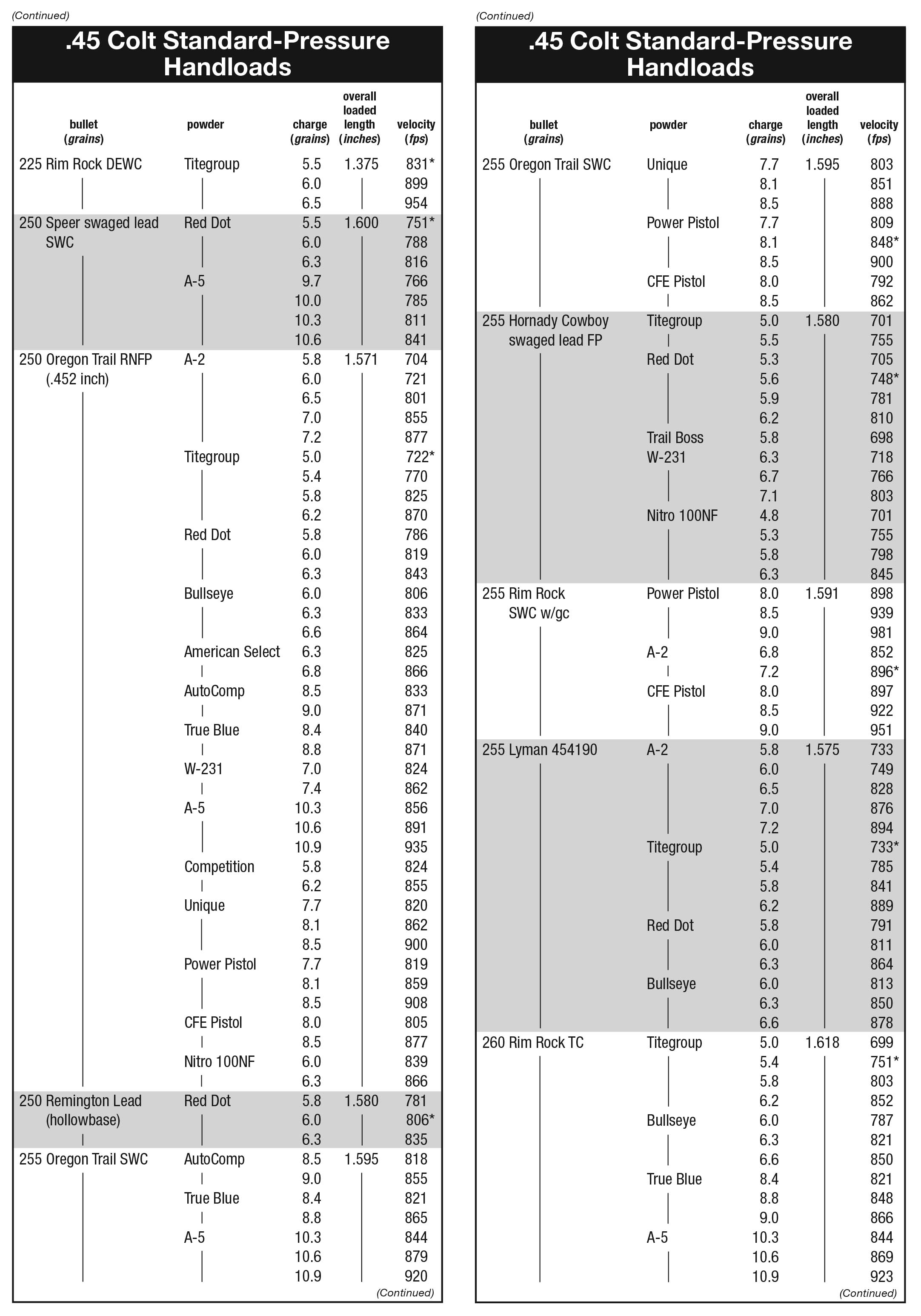

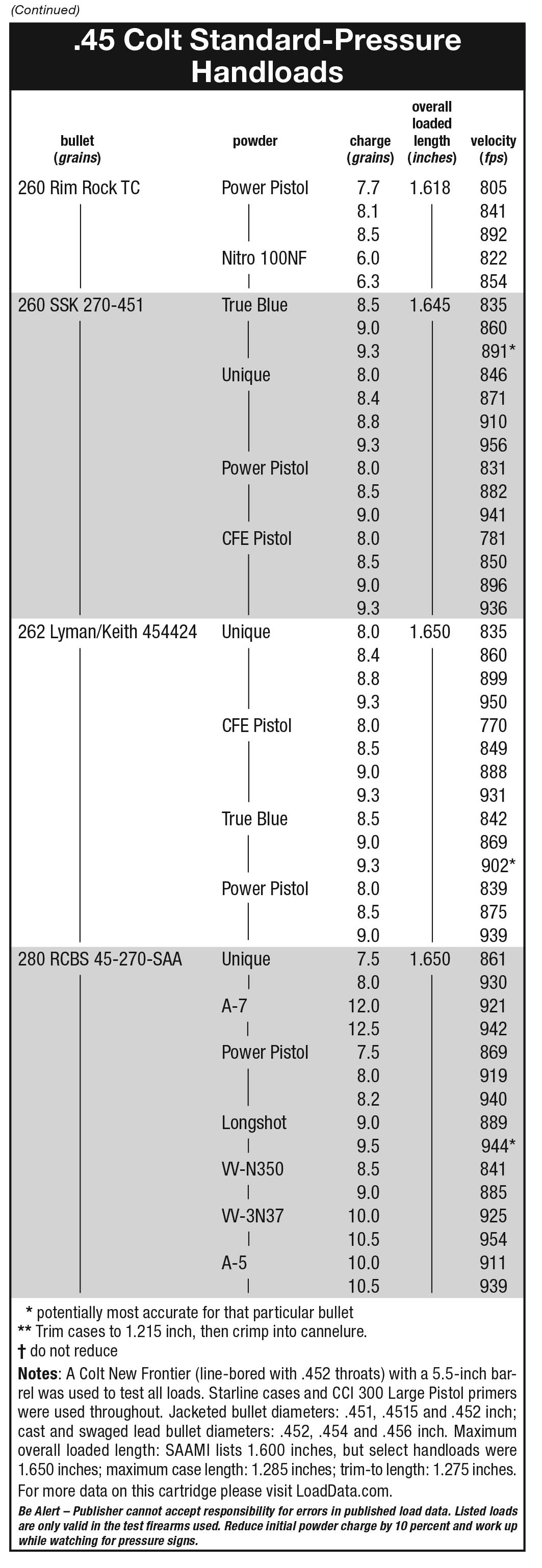

.45 Colt (Pet Loads)

Standard-Pressure Handloads

feature By: Brian Pearce | June, 19

The .45 Colt is rapidly approaching 150 years in existence, and it remains one of our finest, most useful, versatile and handloaded sixgun cartridges. It is often associated with its vital role in settling the western frontier, where it found favor with lawmen, outlaws and anyone that needed a potent sixgun. It has many additional virtues, primarily its big-bore performance and reliability.

The .45 Colt’s origins started in 1871 when Colt began designing a new sixgun specifically to house metallic cartridges. It was submitted to the U.S. Army in 1872 and would become known as the Colt Single Action Army, Model of 1873, Peacemaker, Model P, “Thumb Buster” and a host of other affectionate names. While there were multiple experiments with different cartridges, the .45 Colt was a joint development between Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company and Union Metallic Cartridge Company. The revolver and ammunition were officially adopted for service in 1873.

Contrary to what has been traditionally published, records indicate that early loads from Frankford Arsenal contained a copper case loaded with a 250-grain, roundnose flatpoint lead bullet pushed with 30 grains of black powder, with additional charge weights soon added. (In fairness, many historians maintain that original loads contained 40 grains of black powder with 255-grain bullets, including noted Colt authority John Kopec.) With multiple powder charge weights there has been considerable confusion on this subject. Nonetheless, the 30-grain charge with a 250-grain bullet reached around 850 fps from a 7.5-inch barrel. Exactly when the .45 Colt factory load containing 250-grain bullets propelled by 40 grains of black powder was first offered is unknown, but it was probably assembled at the Colt factory. However, the first known commercial listing is found in the 1880 UMC catalog. I have tested vintage loads that produced an honest 1,000 fps. It is clear why the .45 Colt had such a stellar reputation as a “man stopper” and for its effectiveness on game. Incidentally, the U.S Cartridge Company first listed a 255-grain bullet with 35 grains of black in 1882, but

that charge was increased to 38 grains by 1898.

The .45 Colt was soon loaded with smokeless powders with loads eventually standardized with 250- and 255-grain lead hollowbase bullets from Remington and Winchester, respectively, at around 870 fps, but today are listed at 860 fps. In 1898, Colt made the necessary changes to permit its guns to be used with smokeless powders; however, it wasn’t until 1900 (revolvers with serial number 192,000 or higher) that Colt began to officially warrant its guns for such. Contrary to popular belief, the Mason patented spring-loaded, cylinder-pin release catch first appeared in 1896 around serial number 164,000, which were still “black powder” guns.

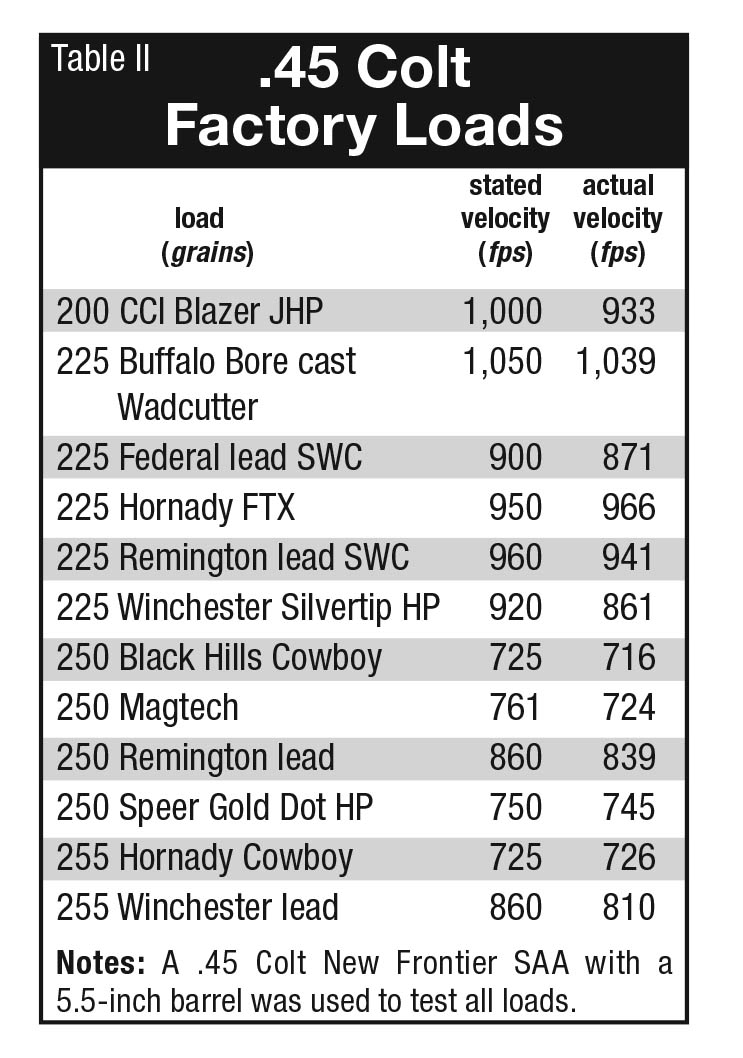

In spite of the above factory loads featuring the old Government bullet profile with a relatively small meplat, they are still effective. I have used them to take big game, including mule deer and bears. In his classic 1955 book Sixguns by Keith, Elmer Keith stated, “As one grows older and his hair starts to turn grey, his respect for this grand old load increases. If I had to shoot only one factory ammunition the rest of my life, I would

take the .45 Colt as my game and defense cartridge.” It is noteworthy that this statement was made 20 years after the development of the .357 Magnum, a cartridge Keith also tested and used in the field.

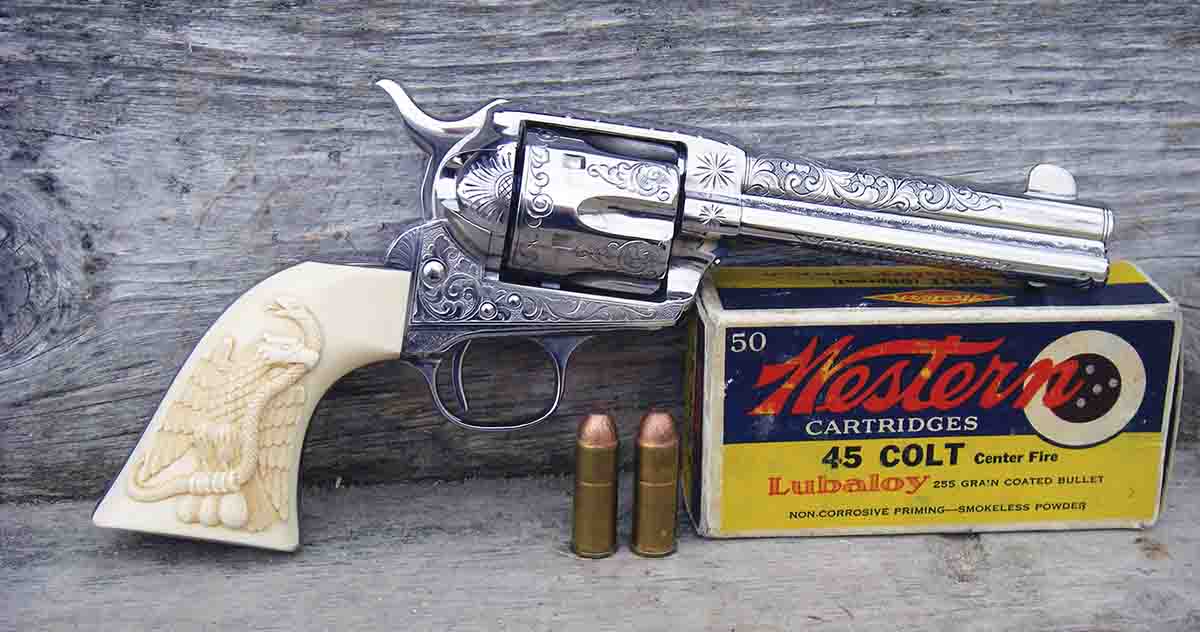

During my early teenage years I acquired a beautiful pre-World War II Colt SAA .45 that was customized by one of the masters during the 1920s. It was outfitted with adjustable sights, a 5.5-inch barrel, one-piece checkered walnut stocks and was timed precisely with an outstanding trigger pull. This revolver and cartridge proved to be a great teacher as I learned how to shoot a big-bore single-action sixgun accurately. After a long day’s work on our remote cattle ranch, I would cast bullets and handload ammunition in the evening so that I could continue shooting the next day. I soon developed an appreciation for reliable performance on game using

flatpoint Keith-style bullets. It served me well while riding the ranch on horseback, running a trap-line, hunting big game, varmints and pests, etc., and it even saved my skin a time or two.

Energy in foot-pounds (ft-lbs) is not a good method to measure a straight-walled cartridge’s effectiveness, particularly when using nonexpanding bullets. For example, the .45 Colt with a 255-grain bullet at 860 fps (Winchester) generates 419 ft-lbs, while the .44 Magnum with a 240-grain bullet at 1,180 fps (Remington) generates 741 ft-lbs. Although far from perfect, the old Taylor Knock Out (TKO) formula, which is caliber x bullet weight x velocity ÷ 7,000, is far more accurate. Again using 255-grain factory loads at 860 fps, the .45 Colt reaches a factor of 14.09, while select standard-pressure handloads containing 280-grain bullets pushed to 950 fps factor at 17.17. For comparison the above .44 Magnum factory loads (which are admittedly conservative) have a TKO factor only slightly higher at 17.35. The .44 Magnum is a great cartridge that offers a flatter trajectory and helps to make hits easier at longer distances; however, this added performance comes at the cost of greater pressures, heavier guns, increased recoil and muzzle report. The .45 Colt operates at notably less pressure, produces a slower, more

moderate recoil and substantially less muzzle report.

The accompanying standard- pressure handloads are within SAAMI guidelines of 14,000 psi, making them suitable for modern Colt SAA revolvers and all guns chambered in .45 Colt that are designed to fire smokeless powder ammunition.

The standard groove diameter for the .45 Colt is .451 inch minimum and .452 inch maximum. I have dozens of references from credible sources that state pre-World War II Colt revolvers feature a barrel groove diameter of .454 inch while postwar guns measure .451 to .452 inch. For example, the most recent Speer Reloading Manual Number 15 states, “Prior to 1945, most .45 Colt revolvers had a bore diameter of .454 inch. After that date bore diameters were reduced to .451-.452 inch, the same as the .45 Auto.” I can only assume the above statement of “bore diameter” was intended to indicate groove

diameter. A quote from Lyman Reloading Handbook, 49th Edition states, “The grooves of pre-World War II revolvers normally measure .454” in diameter. Later production revolvers and lever action rifles are built with .451” diameter grooves.”

This statement has been repeated many times but holds very little truth. More than 45 years of shooting and slugging the barrels of hundreds of Colt SAAs suggests differently. In preparation for this article, I pulled from my personal collection a Colt SAA with serial number 16xxx (1875) that slugged an average groove diameter of .450 inch. Also slugged were guns 121xxx (1887) and number 134xxx (1890) that measured .4515 inch and .451 inch, respectively. For clarification, the above three

revolvers are completely original with barrels featuring the small rounded bead-type

rifling. These figures correspond with the many other pre-World War II guns that I have slugged.

Additional evidence can be found in Colt-published specifications dated June 1924 that list the .45 Colt with a groove diameter of .451 inch minimum and .452 inch maximum (with bore diameter being .444 inch minimum and .445 maximum). In slugging the barrels of later pre-World War II guns with wider flat lands, serial numbers 347xxx (1924) and 355xxx (1936), along with two factory

replacement barrels from the 1930s, each slugged between .451 and .4515 inch.

As always there are occasional exceptions, including two guns manufactured in 1900 and 1902 that slugged .458 and .453 inch, respectively, but they seemed to be more out-of-spec than the normal. Again, a groove diameter of .451 to .452 inch remains standard by all manufacturers.

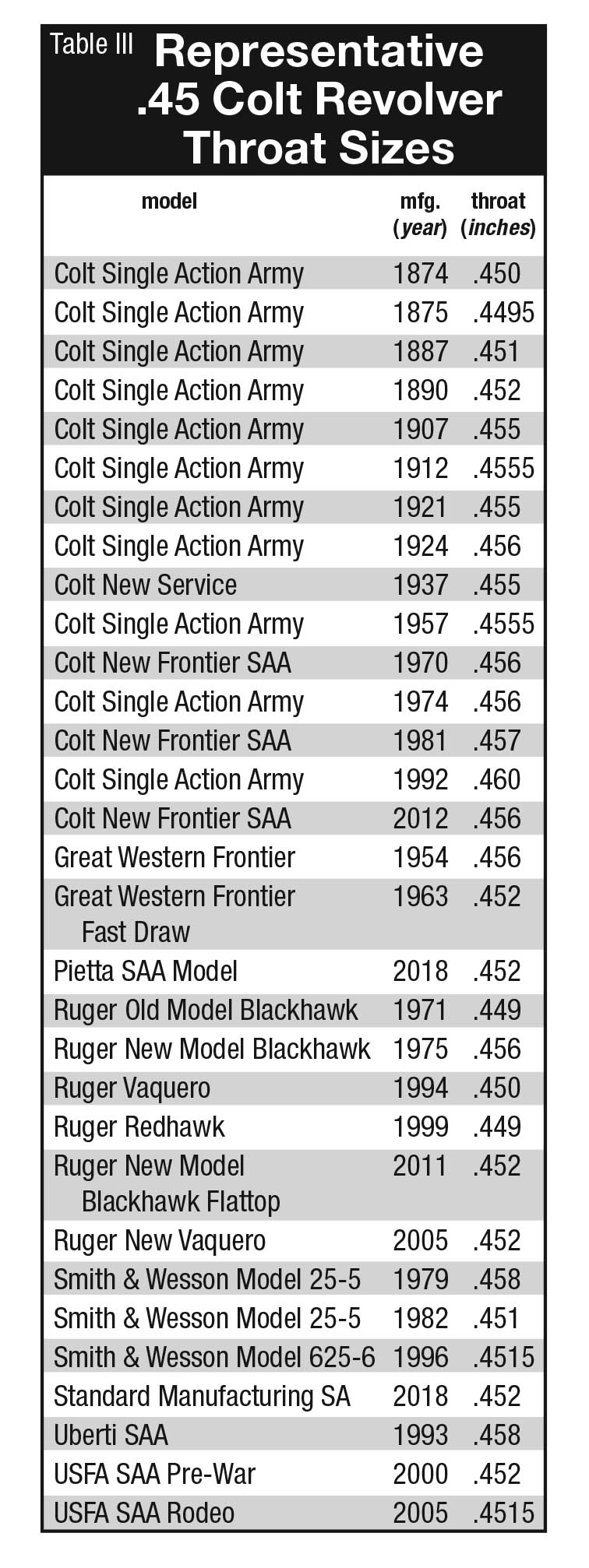

What has varied significantly is the throat diameter (“ball end,” “chamber mouth”, etc.) from virtually all manufacturers including Colt, Smith & Wesson, Ruger, Great Western, USFA and Uberti. Knowing this measurement for a given revolver is critical to select the correct components to achieve accuracy. I have measured Colt revolvers with throats that run from

.449 inch to .460 inch, and Smith & Wesson’s from .451 to .458 inch. Many early black-powder-era Colt revolvers (1873-1898) feature .449- to .452-inch throats that corresponded reasonably with .450- to .452-inch barrel groove diameters.

Soon after smokeless powder came into use, throats were increased to .4555 inch (according to Colt specifications), which worked fine with .456-inch lead hollowbase bullets contained in Remington and Winchester ammunition. This is probably when it became so common to use cast bullets sized to .454 inch with pre-World War II guns but was largely confused with groove diameter. Today the throats of most Colt revolvers measure .457 to .458 inch, which is the same dimension used by Smith & Wesson during the late 1970s, Uberti and others. The Colt factory has told me these large throats are intended to keep chamber pressures low, which is nonsense. Generally, when revolvers with such grossly oversized throats are fired with modern cast and jacketed bullets accuracy is poor. Most manufacturers have recognized the need to offer revolvers with correct throat dimensions including Smith & Wesson, Ruger, Uberti, USFA and others, but not Colt.

When using a revolver with large throats, there are solutions to improve accuracy. While only sporadically available as a component, the Remington .456-inch 250-grain lead hollowbase bullet will obturate to minimize bullet tilting. Cast bullets can be sized to .455 inch (assuming the mould casts bullets large enough), which again helps to reduce bullet tilting in the throat. If cast soft enough they can also slug up to create a gas seal, which helps reduce fusion and barrel leading. However, this approach causes some bullet deformation by being shortened, then sized down in the barrel, which still leaves accuracy potential on the table. For handloaders shooting modern Colt SAAs that feature oversized throats and want to use modern cast and jacketed bullets, the best option is to change cylinders with one that is chambered correctly. In my opinion, throats that measure .452 inch are generally ideal with a variety of bullets.

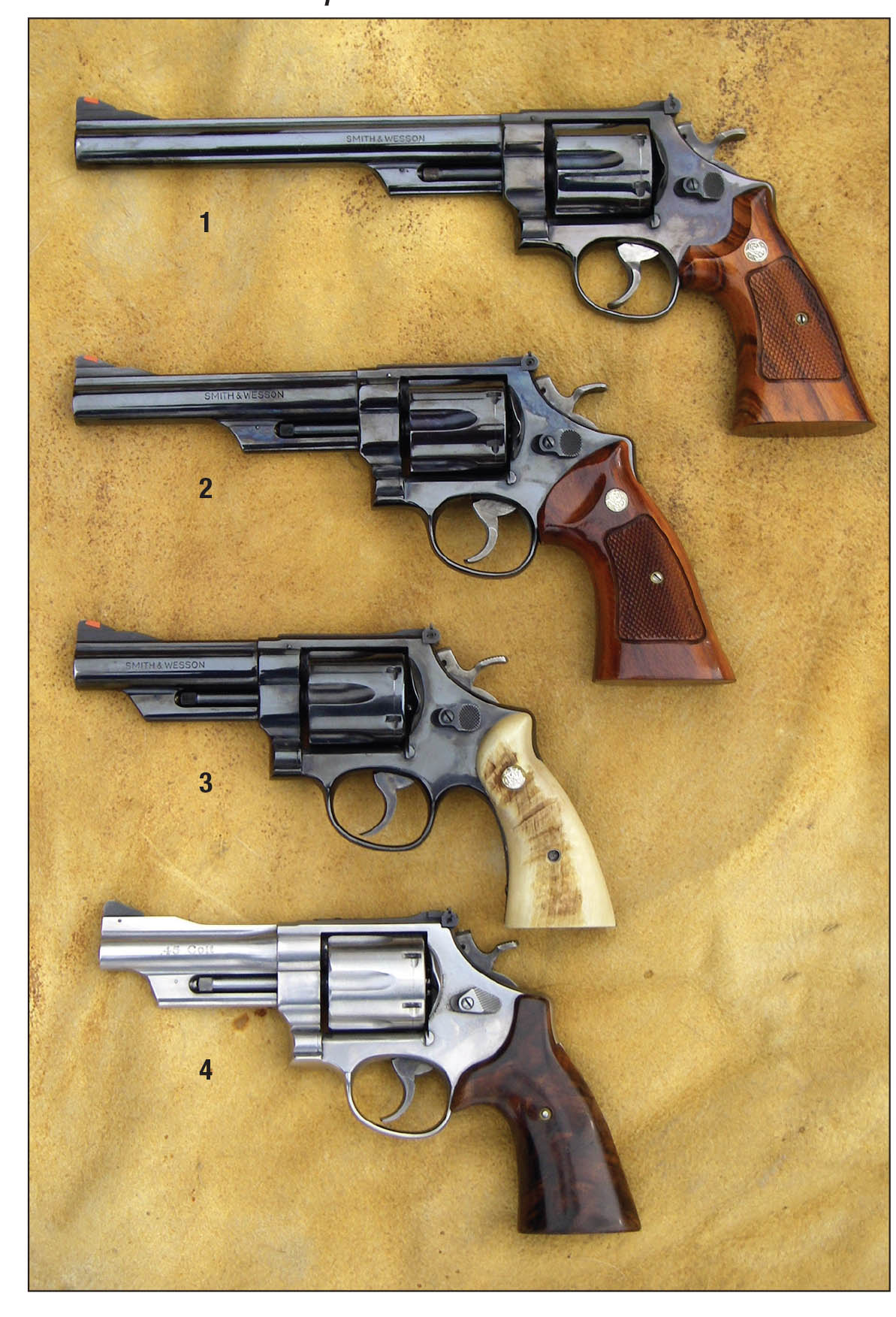

For developing the accompanying data, a 1970 vintage (second generation) Colt New Frontier SAA with 5.5-inch barrel was

selected. This revolver is fitted with a new line-bored cylinder that is tightly chambered with .452-inch throats, a .003-inch barrel/cylinder gap and the forcing cone cut to 11 degrees. This significantly improved its accuracy when compared to the original cylinder with its typical oversized throats, and resulted in increased velocity. A gun with these internal dimensions offers a much fairer assessment of the accuracy potential of all data.

Balloonhead cases were discontinued around World War II but still show up regularly on handloaders’ benches. For several reasons they should not be used. The accompanying data was developed using Starline cases that are strong, offer long life and are available factory direct.

Redding’s excellent Dual Ring Carbide sizing die was used to prep cases as it works the case less, results in longer case life, seems to improve accuracy and eliminates the “Coke bottle” shape forward of the head. It is also noteworthy that many dies manufactured prior to around 1980 fail to size cases adequately to correctly hold .451/.452-inch bullets.

I usually select an expander ball that is at least .003 to .004 inch smaller than bullet diameter, which helps prevent bullets from jumping crimp and aids in achieving consistent powder ignition. However, when using soft swaged-lead bullets, an expander ball around .002 inch smaller than bullet diameter is preferred. This prevents bullets from being “sized” down when seated into an overly tight case.

A roll crimp is generally preferred and should be applied as heavily as the bullet’s crimp groove or cannelure will permit. When using bullets designed for the .45 ACP that don’t have a crimp cannelure, a taper crimp applied after bullets are seated to the correct overall length is the best option. I use the same industry measurement as the .45 ACP – .470 inch.

Most of the accompanying handloads are within industry overall length guidelines at 1.600 inches or less; however, a few loads exceed that length (including Hornady’s FTX factory load). These will still work in the vast majority of sixguns with the exception of the old short cylinder Smith & Wesson N-frames produced prior to 1978 and a couple of others not commonly encountered.

There are many outstanding cast bullets for the .45 Colt. For example, Lyman mould No. 454190 (255 grains) shares a similar profile as the original Government bullet but is a plainbase design that is generally very accurate and can be sized to around .454 to .455 inch for guns with larger throats. It should be crimped over the ogive and seated to an overall cartridge length of around 1.575 inches, which helps reduce case capacity and results in lower extreme spreads with powders that tend to be position sensitive. In guns with .452-inch throats, the Magma designed 250-grain RNFP offered by most commercial cast bullet companies (Oregon Trail used here) can be surprisingly accurate. But in guns with large throats, don’t expect top accuracy from any bevel-base bullet.

Rim Rock’s 255-grain SWC with gas check is accurate and alleviates leading issues with revolvers (or barrels) that are prone to that. It’s also a good choice for hunting. Bullets from RCBS mould 45-270-SAA, which usually weigh around 280 to 285 grains, are designed to maximize powder capacity, are accurate and an excellent choice for hunting big game. However, due to their heavier weights and increased barrel time, many fixed-sighted sixguns may group high.

There are many good jacketed bullets for the .45 Colt. However, when using versions that weigh 250 grains, it is sometimes difficult to reach high enough velocities to achieve reliable expansion while staying within industry pressure guidelines. Jacketed bullets are also more difficult to push down the bore and therefore produce less velocity than a cast bullet of equal weight. Due to their reduced velocity combined with greater resistance in the bore, I don’t recommend loads that produce less than 750 fps because there is a significant chance of sticking a bullet in the bore. I prefer to use 250-grain jacketed bullets in conjunction with +P loads, which is a subject for another day. If reliable expansion is desired, consider 230-grain JHP bullets designed for the .45 ACP or the Hornady 225-grain FTX, which can be pushed close to 1,000 fps while staying within pressure guidelines. Incidentally, many jacketed bullet loads will produce higher velocities in revolvers with shorter barrels.

The .45 Colt is a grand cartridge that has survived because it is so good. In addition to outstanding terminal performance and accuracy in guns with correct internal dimensions, it offers low pressures, mild muzzle report and controllable recoil, all of which make it especially practical for an outdoorsman who uses a sixgun daily.