Learn To Reload (Handloading Basics)

All About Primers

feature By: John Haviland |

Handloaders handle primers by the millions each year and expect each and every one of them to reliably ignite a powder charge. Despite that expectation, many handloaders seem to have a rather carefree attitude

toward primers and consider them no more hazardous than common matches. The priming compound is a pressure-sensitive explosive, though, and primers should be treated with care.

During the last two centuries, continual improvement of primers has been just as important to handloaders as smokeless powder. Alexander John Forsyth is credited with developing fulminate of mercury as a percussion system (1805) that could be detonated by a firearm’s hammer. American Joshua Shaw is recognized as inventing the percussion cap in 1814, finally settling on a mixture of fulminate of mercury, chlorate of potash and powdered glass. This primer compound was very volatile.

The arrival of centerfire cartridges resulted in the primers recognized today. Black powder fouling left in cases absorbed most of the mercury from those first centerfire primers, but a stronger primer was required to reliably ignite smokeless powder, which arrived in the 1890s. Plus, little fouling left by smokeless powder allowed mercury to penetrate into brass cases, weakening and making them unsafe to reload.

By 1900, mercury had been removed from primers. Primers still remained corrosive to barrel steel and required immediate cleaning to prevent rust. Potassium chloride was the cause and it, too, was eventually removed from primers. In 1927, Remington introduced its Kleanbore noncorrosive primers.

Heavy metal-free (mostly lead) primers have been on the market for years. According to some experts, they have not been deemed dependable enough for all-around use.

Federal hopes to change that with its Catalyst primers. Catalyst primers do not contain any heavy metals, said Drew Goodlin, senior director of technology at Vista Outdoor, the company that owns Federal Ammunition. Making the ingredients and bringing them together into a primer mixture for

the Catalyst is not as volatile and makes them safer to manufacture. “Powder is not easy to ignite, and compressing it in a case makes it even more difficult to ignite,” Goodlin said. The Catalyst formula drives more hot metal particles into powder than other primers to reliably ignite powder.

Only time will determine the Catalyst’s success. “It will take 10 to 15 years to see if Catalyst primers work out,” he said.

Primer Types

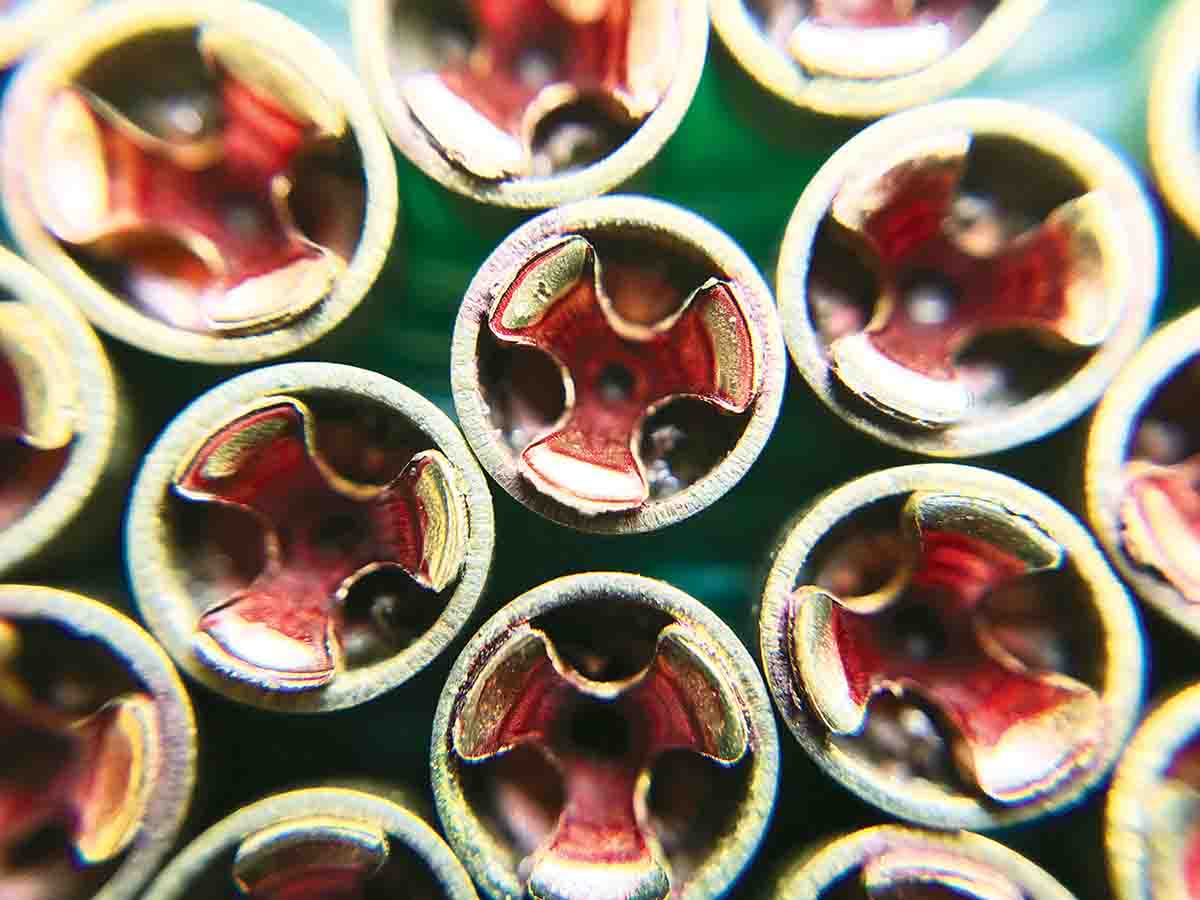

Berdan and Boxer are the two types of primers. Berdan primers fit in a case primer pocket featuring a pillar-like anvil in the center and a flash hole on each side. About the only place Berdan primers are found in the U.S. are in cartridge cases made of steel or aluminum, which are unsuitable for reloading. Boxer primers incorporate a built-in anvil and work exceptionally well with standard cases that feature a primer pocket with a central flash hole. Boxer primers are easy to remove from cases with the decapping pin in a sizing die. Most modern primers are of this type.

Boxer primers are made in three sizes: small, .175-inch diameter; large, .210-inch diameter; .315-inch diameter for the .416 Barrett and 50 BMG. Further segregated under the “small” heading are small rifle, small rifle magnum, small pistol and small pistol magnum. “Large” primers include large rifle, large rifle magnum, large pistol and large pistol magnum.

Additional differences include composition of the priming mixture, cup thickness, sensitivity and a slight variation in height.

Primer manufacturers classify their primers by a system of numbers or letters. CCI Small Rifle standard primers are numbered 400, and CCI Small Rifle Magnum primers are 450. Small pistol primers are 500 while Small

Pistol Magnum primers are 550. Winchester Large Rifle primers are WLR, and Winchester Large

Rifle Magnum primers are WLRM. To remove any confusion, cartons of all U.S.-manufactured primers are printed with the exact type of primer enclosed.

Primers of the same type vary between brands. Lyman Reloading Handbook, 50th Edition lists a pressure difference of 2,600 psi among five different types of standard large rifle primers firing the same .308 Winchester load, so it’s prudent to use the exact primer listed in reloading data.

Years ago, the advice was to use, where applicable, standard large or small rifle primers to ignite cylindrical powders in cases up to the size of the .30-06. For spherical powders, small rifle magnum primers were suggested when using 30 grains or more. Magnum large rifle primers were recommended for spherical powders and heavier amounts of cylindrical powders. Standard handgun primers were suggested for standard and magnum cartridges loaded with flake-type powders, and magnum handgun primers were suggested to reliably ignite spherical powders in magnum cartridges.

Some handloading manuals still mostly follow these suggestions, such as Speer Handloading Manual Number 15. Others list all types of powders to use with standard rifle

primers in standard cartridges and magnum large rifle primers in cartridges with “magnum” at the end of their names. Magnum handgun primers are mostly limited to magnum handgun cartridges.

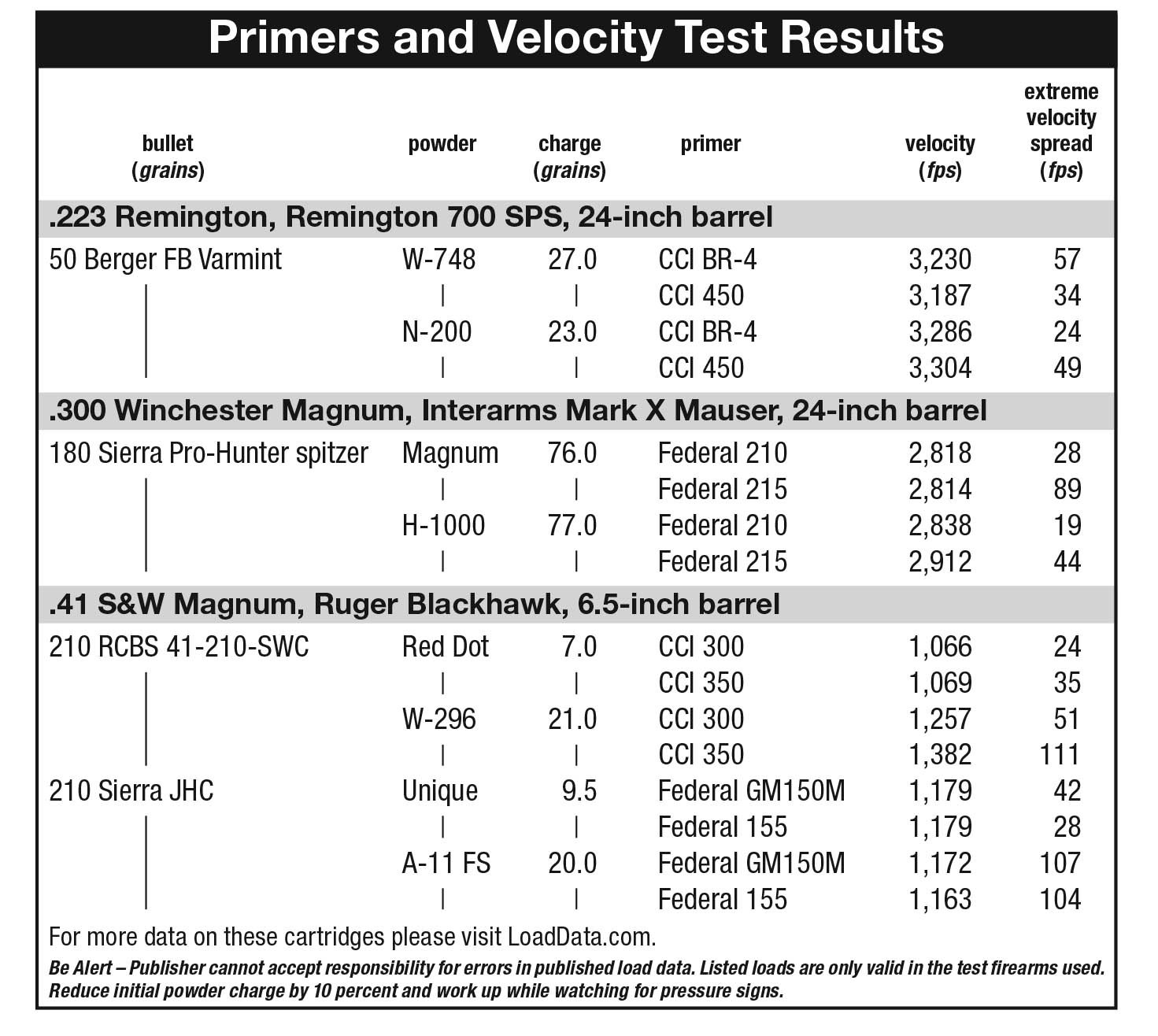

I conducted a limited experiment during a 30-degree Fahrenheit day to determine the difference between standard and magnum rifle primers firing cylindrical and spherical powders in the .223 Remington and .300 Winchester Magnum, and standard and magnum large pistol primers in the .41 S&W Magnum loaded with flake and spherical powders.

I loaded Norma 200, a cylindrical powder, and W-748, a spherical powder, in Winchester .223 Remington cases with CCI BR-4 standard and CCI 450 Small Rifle Magnum primers. The loads were topped with Berger 50-grain FB Varmint bullets.

When igniting Norma 200 powder, the magnum primer produced 18 fps higher velocity with the Berger 50-grain bullets when compared to standard primers. However, the extreme velocity spread was double at 49 fps for the magnum primers as compared to the standard.

With W-748, the BR-4 primers produced 43 fps higher velocity when compared to the loads with the 450 magnum primers. The BR-4 primers, though, produced an extreme velocity spread of 23 fps higher than the loads with the 450 magnum primers.

In .300 Winchester Magnum cases I fired spherical Ramshot Magnum and cylindrical H-1000 powders with standard Federal 210 Large Rifle and Federal 215 Large Rifle Magnum primers. Velocities for Sierra 180-grain bullets were nearly the same with Magnum powder fired by standard and magnum primers.

Extreme velocity spread was three times higher with the magnum primers as compared to standard primers. Magnum primers produced 74 fps higher velocity than standard primers firing H-1000 powder.

Except for one .41 Magnum load, there was not much difference between large pistol magnum and standard large pistol primers. Velocity and extreme velocity spread were fairly consistent with Sierra 210-grain bullets using flake-type Unique and spherical Accurate 11 FS powders with Federal GM150M Large Pistol and 155 Large Pistol Magnum primers. CCI 300 standard and 350 magnum primers delivered pretty much the same velocities and extreme velocity spreads when using a light amount of flake-type Red Dot powder. The CCI magnum primers generated an additional 125 fps with spherical W-296 powder compared to standard primers. Extreme velocity spread using the magnum primers was double that of the standard primers.

Primers certainly play a part in accuracy. In the brief test with the Remington 700 SPS .223 Remington, CCI BR-4 primers produced .45-inch groups with Berger 50-grain bullets loaded with W-748, and .48-inch groups with Norma 200 powder. In contrast, groups shot with CCI 450 magnum primers measured .92 inch with W-748 and .89 inch with Norma 200 powder.

Seating and Primers

Primers detonate by a firing-pin strike on the face of the cup, yet primers are seated in cases with a forceful push on the face of the cup. So it should go without saying, undue force must be avoided when seating primers. A primer sideways in the sleeve of a primer seating arm on a reloading press is easily crushed by the leverage of the press handle. A slow and even pressure should be used when seating a primer.

Handheld priming tools allow a handloader to feel when the primer is seated properly. Most tools include a safety block that separates the primer being seated from others in the tray. When the handle is squeezed

completely on a hand tool, primers are seated to the correct depth.

Boxer primers are manufactured with the anvil protruding slightly above the rim of the primer cup. Seating primers to the correct depth butts the anvil against the bottom of the primer pocket in the case and pushes the anvil into contact with the priming pellet to “sensitize” it for proper ignition.

The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) states primers should be seated flush to .008 inch below the face of the case head. Slightly below flush is correct. You could measure that depth with the rod end of a caliper. However, running a finger over seated primers allows a handloader to feel that primers are properly seated below flush.

Seating primers too deeply requires a lot of force that only comes from the leverage of the handle on a press. That force crushes the primer pellet, which most likely results in a misfire.

Troubleshooting

Primers may misfire for a variety of reasons, and the primer is often blamed. However, the reason can usually be traced back to improper primer seating and case sizing.

Primers that are not fully seated in their pockets (in combination with a weak firing-pin strike) are the most likely reason for misfires. A primer with its anvil not in contact with the bottom of the primer pocket requires a firing pin to use some of its force to fully seat the primer into the pocket, and not enough force remains to give the primer a solid strike.

Misfires can also occur because cases are too short at the shoulder due to excessive case sizing. As a result, a handloader may only hear the click of a falling firing pin because it did not have enough reach to give the

primer a solid hit.

In my CZ 527 Carbine, some primers failed to fire 7.62x39 cartridges. A shallow indent on the primers was the obvious cause. There was no buildup of gunk around the firing pin assembly to hinder the firing pin. It took some investigating, but I finally determined the 7.62’s low maximum average pressure of 45,000 psi did not expand cases to fill the chamber and that, together with the force of large rifle primers, caused case shoulders to be pushed back considerably.

I used a headspace gauge to measure the shoulders of factory-loaded Hornady Black 7.62x39 cartridges before and after they had been fired. The shoulders shortened .005 inch after firing. I measured the shoulders of four of the once-fired Hornady cases after they had been fired with only a Remington 9½ Large Rifle primer. The cases shortened more on the shoulder each of three times after only a primer was fired. The solution was to expand the case necks and then size down the necks until cases fit tightly in the CZ’s chamber, creating a false shoulder with a tight fit in the chamber.

Handloaders expect a lot from primers. Handle them with respect, select the proper one for your loads, seat them correctly and each and every primer will reliably ignite a powder charge.