The Modern 7x57

Loads for a Versatile Cartridge

feature By: John Barsness | June, 19

What does matter is the 7x57’s origin as a military cartridge, back when new-fangled smokeless cartridges were normally loaded with heavy, roundnose bullets, like the black-powder cartridges they replaced. The 7x57’s original load was a 173-grain roundnose at around 2,300 fps, which required a rifling twist of one turn in 220 millimeters (8.66 inches). As with several early smokeless military rounds, this relatively fast twist inadvertently made the 7x57 very versatile because it could handle a wide range of bullet weights and styles, including lighter, faster and more streamlined bullets.

Quite a few, however, regarded it as more suitable for those unfortunate humans who somehow could not tolerate the recoil of a .30-06. One such evaluation came from the firearms columnist for Field & Stream, Capt. Paul Curtis, in the chapter “Big Game Rifles” in his 1934 book Guns & Gunning: “Next to the [.30-06] Springfield, the 7 m/m (.276) is probably the best. In it we have a choice of either a 175 grain bullet at 2300 feet velocity or a 139 grain bullet at 3000 feet velocity . . . With it the biggest game on the American Continent has been killed. Mrs. Curtis has used it on several expeditions with complete satisfaction. For the man who is

The 3,000 fps of the 139-grain bullet was fiction, published by more than one ammunition company back when very few shooters could even spell “chronograph.” Around 2,700 fps was more realistic, but even at 2,700 a 139-grain spitzer shot far flatter than a 175 roundnose at 2,300.

Eventually enough hunters liked the 7x57 that, as handloading became more popular, they realized other bullets could make it even more versatile. Philip B. Sharpe’s 1937 book, Complete Guide to Handloading (the first BIG loading manual published in the U.S.), lists nearly 100 loads for the 7x57.

About that time, a young gun writer Jack O’Connor was an early admirer and handloader of the round. Eventually O’Connor started handloading 160-grain spitzers, and as he grew older and apparently less recoil tolerant, started using the 7x57 more than the .270 Winchester. Among the chapters in his 1970 book, The Hunting Rifle, is one on the 7x57 titled “Big Punch in Little Case.” The opening paragraph states the 7x57 “has been used all over the world on everything from dik-dik to elephants and everything in North America from javelina to moose.”

However, O’Connor also mentions that America’s infatuation with the 7x57 “faded out in the 1930’s,” when both Remington and Winchester dropped the chambering. After World War II, when firearms factories started making hunting rifles again, the 7x57 failed to reappear. However, this changed over the next few decades, partly due to Ruger offering it as standard in both the Model 77 bolt action and No. 1 single shot.

Eventually, the 7x57 became a “special run” cartridge, only appearing occasionally in American sporting rifles, especially after the 7mm-08 Remington appeared in 1980. The 7mm-08 solved one new problem of manufacturing modern 7x57 hunting rifles, along with an old problem.

The new problem was so many hunters preferring “short” bolt actions with magazines about 2.85 inches long: The 7x57 simply would not fit, since overall cartridge length was

The old problem arose from the 7x57’s original 173-grain roundnose, which required a very long chamber throat. This worked fine with heavier bullets, but accuracy could be iffy with lighter bullets. This wasn’t a factor back when very few hunters used scopes, but by the time O’Connor published The Hunting Rifle, scopes were standard equipment, and many handloaders had become obsessed with sub-inch groups at 100 yards.

During the same period, nonhandloading hunters became obsessed with velocity, due to the magnum mania that began after the war. Factory 7x57 ammunition in America has always been “downloaded” considerably, both because of old, relatively weak-actioned rifles (including Remington Rolling Blocks), and because after the 7x57 was transformed from a military cartridge into a hunting round, throat length varied a lot.

I have owned several 7x57s, among them two pre-’98 Mausers, a Remington 700 Mountain Rifle, two Ruger No. 1As, a Ruger 77 Mark II, two factory rifles on commercial ’98 Mauser actions and four custom rifles. The longest throats were in the old Mauser military rifles and a Ruger No. 1A, a “red pad” model already well-used when I acquired it in 1992.

The Ruger’s throat was also apparently wide as well as long, because it would not shoot worth a hoot unless bullets were seated nearly touching the lands. The only lead-core spitzers long enough to reach the lands weighed at least 160 grains, and even then the case neck barely grasped the bullet’s base.

The chamber throat in my present 7x57, a custom rifle built a dozen years ago by Serengeti (now Kilimanjaro) Rifles on the “short” Montana 1999 bolt action, is probably the shortest of all my 7x57s. The 1999 action is a sort of cross between the pre-’64 Winchester Model 70 and a commercial ’98 Mauser, and the “short” version is actually what most shooters would

The throat-length difference between the Serengeti and the red-pad Ruger No. 1A was close to half an inch, and all my other 7x57s had throats somewhere in between. Both my second Ruger No. 1A and Ruger Hawkeye had SAAMI standard throats, with the rear end of the rifling starting about .08 inch in front of the case mouth and ending at about .37 inch.

These widely varying throat lengths resulted in widely varying pressures, another reason American 7x57 ammunition tends to be pretty mild. This also complicates loading data, one reason published 7x57 powder charges vary considerably from manual to manual. Some manuals only publish mild data for old rifles while others publish hotter loads, specifying “modern rifles” only.

Due to differences in throat length, both kinds of loads produce considerably different velocities in 22-inch barrels. When I started handloading for my first “modern” 7x57, a custom rifle on a VZ-24 ’98 Mauser action, IMR-4350 proved to be the best powder. In that rifle, 50.0 grains produced about 2,800 fps with the Nosler 140-grain Partition from the 21-inch Shilen barrel. My next 7x57 was the long-throated Ruger 1A, also with a 22-inch barrel, which provided 2,700 fps with the same load, and required 52.0 grains to hit 2,800.

Since then a few other 7x57s with 21- or 22-inch barrels have provided 2,800 fps with only 48.0 grains of IMR-4350 – or H-4350, which I switched to 20 years ago, and generally has a very similar burn rate. This is one reason the Serengeti will probably be my last 7x57: If somebody (including me) inadvertently fires one of my handloads in another 7x57, the pressures will probably be lower because the other rifle’s throat will almost surely be longer.

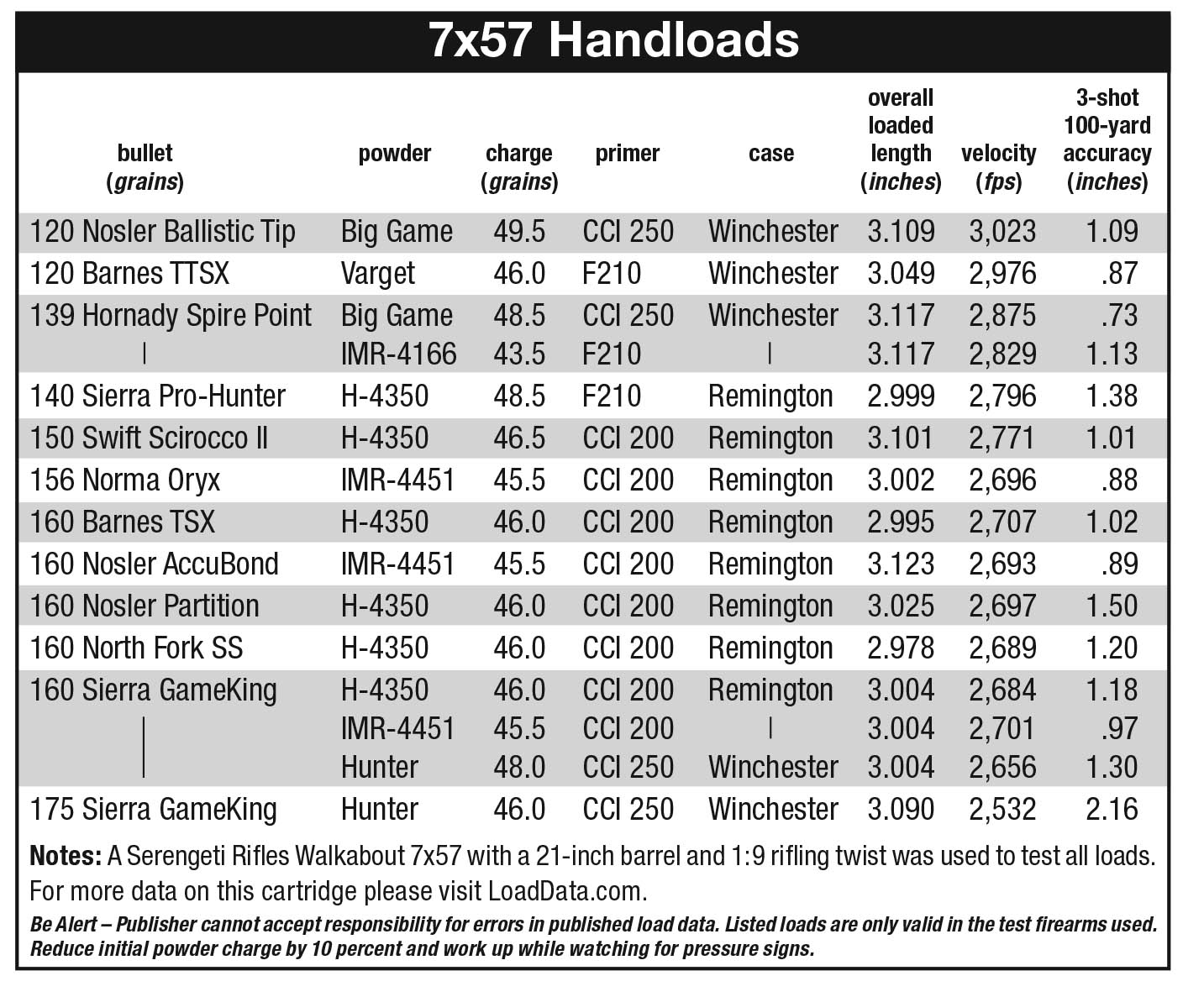

Knowing this does not solve the problem of widely varying loading data, the reason that for years I loaded 7x57s largely by muzzle velocity. With the few sources showing modern rifle-pressure data, top muzzle velocities from 22- to 24-inch barrels are around 3,050 fps for 120-grain bullets, 2,900 for 140s, 2,750 for 150s, 2,700 for 160s and 2,600 for 175s. When muzzle velocities approached those levels, I stopped adding powder, and my handloads never resulted in the slightest sign of high pressure, even in more than 90 degree Fahrenheit August temperatures, whether during southwestern pronghorn seasons or safaris in southern Africa.

However, a couple of years ago it occurred to me that the velocities of modern 7x57 data resembled 7mm-08 Remington data. The reason is simple: The 7mm-08 has almost as much powder room as the 7x57, but the SAAMI maximum average pressure is 61,000 psi, 10,000 more than the 7x57’s “old rifle” maximum. I reasoned that using 7mm-08 data as a starting point would be safe in modern 7x57s, because the slightly larger 7x57 case would result in lower pressure, even in a short-throated rifle.

This would be very handy because as the 7x57’s popularity has faded, very little new load data gets published, especially with newer powders. Western Powders’ manual, for instance, only lists two powders in its 7x57 data, Accurate 4064 and 2700, but the company’s excellent Ramshot Big Game and Hunter powders also have burn rates very suitable for the 7x57. However, their extensive 7mm-08 data includes far more powders, including Big Game and Hunter, so I tried the loads in the Serengeti with excellent results.

Newer 7mm bullets have also appeared, often with higher ballistic coefficients (BC). While many, if not most, handloaders associate high BC with high muzzle velocity, high-BC bullets tend to help considerably, even in moderate-velocity rounds. First, the impact velocity at close range is kinder to cup-and-core bullets, allowing them to expand and penetrate well, and at longer ranges the higher retained velocity helps insure expansion.

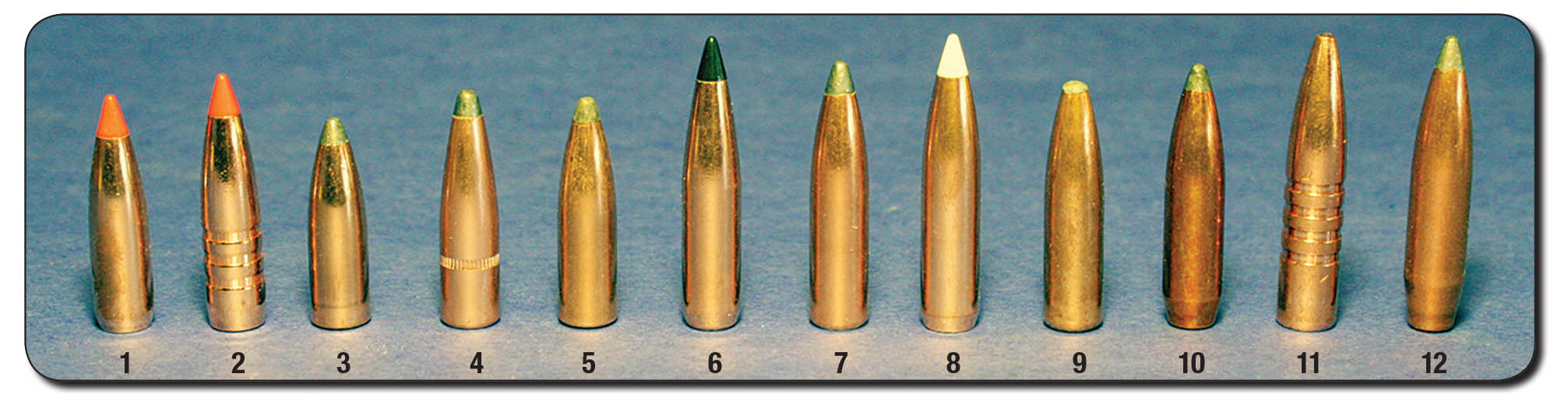

A good example is the Sierra 160-grain GameKing boat-tail softpoint hunting bullet. While the listed BC of .436 is not considered very high today, it was back when I started handloading for the 7x57, and I had a good supply on hand when the Serengeti appeared. After working up a load with H-4350 and trying some other bullets, I discovered the rifle would put any bullet around 160 grains into the same group at 100 yards – which was not the case with lighter bullets. As a result, I used 46.0 grains of H-4350 and the 160 Sierra as my basic sight-in, practice and hunting load for “deer-size” game but loaded other bullets for larger game, including some specifically for field testing.

In fact, in the two years after the rifle was completed, I went to South Africa for a total of seven weeks on cull hunts with some trophy hunting mixed in, using handloads with the 160-grain GameKing and three other bullets; the Barnes 160-grain TSX, Norma 156-grain Oryx and North Fork 160 SS. Most of the culled animals were smaller species, particularly springbok, about the size of American pronghorn with strikingly similar coloration and black horns of about the same length. The rifle was also used on warthog, impala, bushbuck, kudu and wildebeest, so all the bullets got a workout.

I used the tip of the bottom post to aim at the springbok. The Sierra landed within a couple of inches of point of aim and expanded well because the retained velocity was around 2,100 fps. It also worked great on impala and warthog, and in fact, none of the bullets were recovered at any range. They have also always exited North American “deer-size” game.

Useful information was also gathered with the other bullets. I found the Barnes 160-grain TSX at 2,700 fps did not kill nearly as quickly as the Sierra, even on larger game, so since then have generally used lighter, faster Tipped TSXs, both in the 7x57 and 7mm-08. The North Fork 160-grain SS, on the other hand, has a little lead core in the nose and killed pretty well even on springbok, and the Norma 156-grain Oryx both expands widely and penetrates well, though not as deeply as the North Fork. (I did not use either Nosler 140- or 160-grain Partitions in Africa due to already using them plenty in North America. Of course, they work well at 7x57 velocities due to their softer front cores.)

While I have never had any desire to shoot a dik-dik (an African antelope about the size of a white-tailed jackrabbit) or an elephant, I happen to have taken the “extremes” of North American big game described by Jack O’Connor with the 7x57: javelina in Sonora, Mexico, with the 139-grain Hornady Spire Point, and a bull moose in Alberta with the 160-grain North Fork. Both loads worked fine, as has the 7x57 on a total of 15 species of big game in four countries. For the handloader, the modern 7x57 is essentially a slightly down-sized .30-06, and it works just as well for general big-game hunting with about 75 percent of the recoil.