Quality Revolver Handloads

Assembling the Best Loads Possible

feature By: Mike Venturino | June, 19

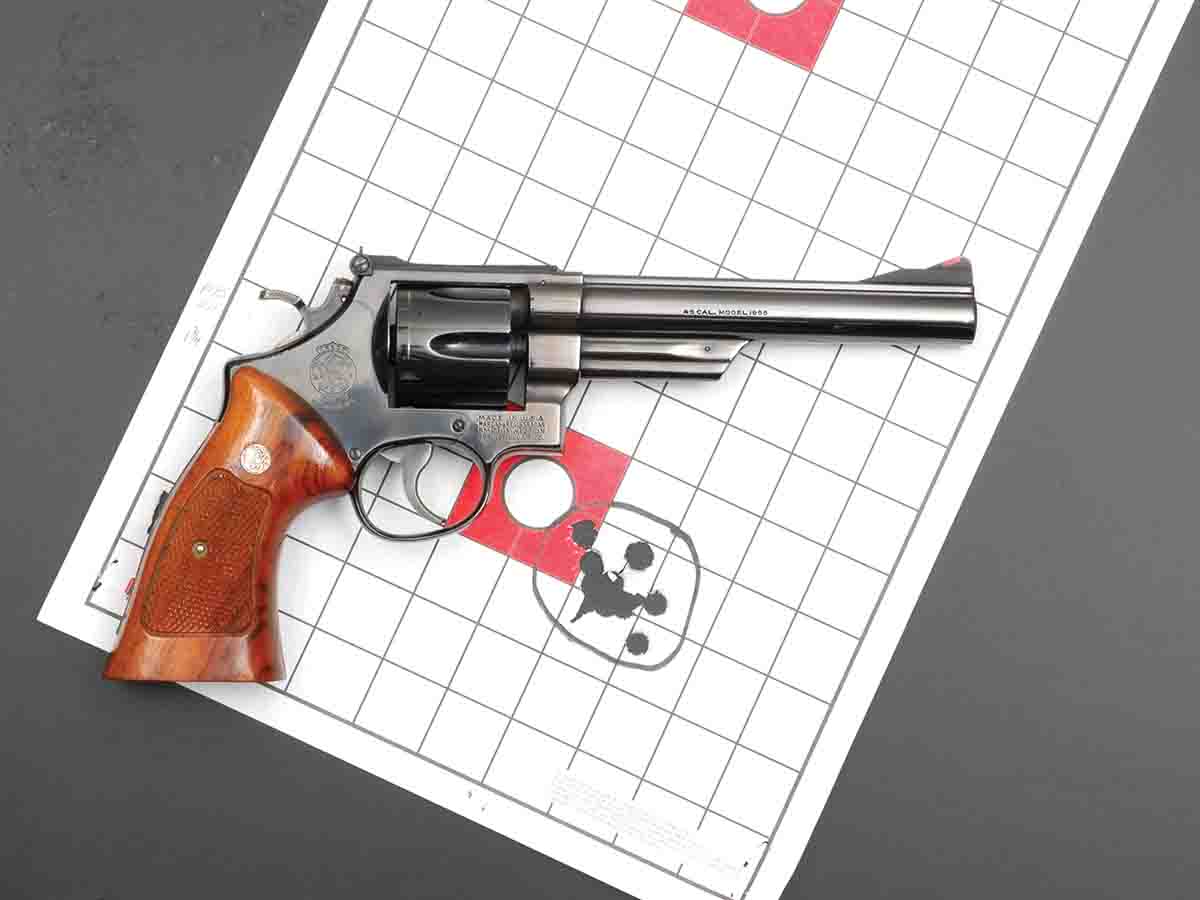

Let’s figure you have a quality revolver and you’re a confident marksman, but does that ensure those tiny clusters gun writers often show? Not at all; it’s also mandatory that good ammunition – darn good ammunition –

Computer techs say, “Garbage in, garbage out.” For handgun shooters and handloaders the matter is much more serious. Besides bad groups on paper, poorly handloaded ammunition can result in damaged revolvers and/or shooters.

There are two basic genres of revolver bullets: lead alloy and jacketed. Let’s look at the former category first. The entire rationale for a loaded cartridge is to deliver a bullet to a specific spot. As an avid bullet caster, it pains me to state the following: Cast bullets need not be perfect to shoot accurately. They may have slight wrinkles, slightly rounded driving bands or grease grooves, and they may be scratched and dented from transit and not give up a smidgen of accuracy.

Way back in my early bullet- casting years, I managed to damage a double cavity Lyman No. 358477 mould (150-grain SWC) so that its bullets were visibly out of round. Before junking it, some of its bullets were loaded in .38 Special cases. Then from a sandbag rest using a Model 19 .357 Magnum with a 6-inch

Then there is the matter of the lead-alloy bullet’s diameter. It should be no less than the actual groove diameter of the revolver barrel, up to about .003 inch over that dimension. It’s more important to match bullet size to the revolver’s chamber mouths. For instance, a Colt SAA has a .451-inch barrel groove diameter but .456-inch chamber mouths. Accordingly, I size bullets to .454 inch or use a hollowbase bullet. Hollowbase bullets can make up for variation in barrel and cylinder dimensions.

Lead-alloy bullets need lubricant unless they are the new coated type with a baked-on covering. I’ve only barely scratched the surface in learning about coated bullets, but my first shooting with them has been very satisfying. Since 1986 I’ve lubed all my homemade bullets with SPG. It is relatively soft and fills the grease grooves completely. If a handloader is buying cast bullets commercially, say packed 500 to a box like so many are, they invariably carry a hard lube. In shipping, this lubricant often will fall out of grease grooves – totally or in part. If I’m striving for the best precision available from revolvers, I don’t use partially lubed bullets.

Inevitably I’m asked what bullet shape someone should use. The answer is contingent on its purpose. There are four basic shapes of lead-alloy bullets: wadcutter (WC), semiwadcutter (SWC), roundnose (RN) and roundnose/flatpoint (RNFP). When I started handloading, it seemed like many writers genuflected when SWCs were mentioned. The older gents who helped me get started in 1966 swore by WCs. Everybody who was anybody who wrote gun magazine articles despised RNs. After more than 50 years of trying about every shape and style of lead-alloy bullet, my favorite is the RNFP. That’s because some of my handloads find their way into tubular magazine leverguns. For this same reason I don’t use any revolver bullets without crimping grooves.

Jacketed bullets were just coming into popularity for revolver handloaders when I started in the mid-1960s. I think of jacketed bullets as mostly a specialized item for most revolver handloading. If a desired revolver handload will provide less than 1,000 fps muzzle velocity, I see no reason to use jacketed bullets. To me they fit best in the magnum revolver scene because their expansion at lower speeds is questionable. Again, purpose should be the determining factor as to whether jacketed hollowpoint (JHP) or jacketed softpoints (JSP) should be used. Stated very simply, hollowpoints are for quick expansion; soft points are for deeper penetration.

Once good quality bullets suited to the task from plinking to hunting are settled upon, the next step is getting them into cartridge cases without ruining them. Accomplishing that requires some attention to detail in case preparation. Case preparation is one of the most boring and seemingly unproductive steps in handloading. Hour upon hour can be spent in case preparation without getting a single finished cartridge. Of course, that is in regard to fellows using standard presses. Handloaders using a progressive press get a finished round with nearly every pull of the press handle. We’ll return to progressives shortly.

At this point let’s assume that the handloader is diligent and has cleaned his brass well and junked any cracked or split cases. Just about all dies for sizing revolver cases are made to the same basic specifications. In short, they will size fired cases down so they chamber in all revolvers made for the same caliber. In my experience I’ve never encountered a revolver sizing die that failed in that respect. Of course, most die sets for straight-walled revolver rounds have inserts of carbide, titanium or some other material so that no case lubrication is necessary. Oddball guys like yours truly who dote on old “bottlenecked” revolver rounds like the .38-40 and .44-40 have no special sizing dies. For such cartridges, I like the Lee case lube. Apply it a few minutes ahead of time and it dries into a powder and doesn’t even need wiping off unless applied in excess.

One of the most important safety aspects of assembling good revolver handloads is seating primers properly. Seated too deeply, they may be damaged to the point of not firing, or firing erratically. Seating primers with too much force may cause them to ignite. Seating them so they sit high out of the primer pocket can cause them to inhibit cylinder rotation in revolvers. In rare cases, such friction can cause ignition before the cylinder has fully rotated, which does nothing positive to revolver or shooter. Well over 50 years ago, I developed the habit of running my finger over a seated primer. The fingertip should glide right over the case head without hanging on a high primer,

What about case trimming? I seldom trim handgun brass, and occasionally that missed step has caused a ruined case. Note the accompanying photo of two .38-40 handloads. The case on the left had stretched enough so the crimp did not align with the crimping groove. The thin case buckled. Normally, I buy cases in 500 to 1,000 round lots, and then they get fired and loaded approximately the same number of times, so trimming isn’t a big factor. Simple logic dictates that if the crimp misses a bullet’s crimping groove it’s time to trim it. Deburring the case mouth on new brass is important. They come from the factory square at the mouth, and unless cases are deburred, they will peel off pieces of bullets.

There is a little-known contributing factor in getting bullets properly seated. Case mouth expanding and belling dies are different in regard to use with lead alloy or jacketed bullets. Expander die plugs for jacketed bullets are a few thousandths smaller. Jacketed revolver bullets must be secured tightly in cases or the slow-burning powders meant for loading magnum revolver cartridges will not ignite consistently. Conversely, expander plugs for lead-alloy bullets are larger so relatively soft bullets are not deformed during seating.

Here are some examples: Lead bullet size for .44 Russian/.44 Special is .429/.430 inch. My RCBS “Cowboy” dies made specifically for lead bullet reloading have a .427-inch

Is this matter of different size expander plugs a safety concern? Not at all; however, matching plugs to lead-alloy or jacketed bullets is beneficial in the search for optimal revolver handloads.

At this point we have good, clean, quality brass with primers seated properly and cases expanded with their mouths belled just enough to accept the bullets’ bases. Hopefully the handloader has picked out a suitable powder and charge. Now let’s move on to powder and seating bullets.

For many years I dropped a powder charge into a case, started a bullet’s base in its mouth and immediately seated and crimped it; never did I suffer a double charge or no charge. More recently, I have taken to filling my many loading blocks with charged cases, then standing over them with a small but powerful flashlight to check powder levels. Knowing all is well I then start bullets in case mouths and seat them all at the same sitting. I have never had any problems using this method.

One problem many handloaders encounter in loading for revolvers is having the proper seating stem for their dies. Some are cut for RN bullets and some for SWCs or RNFPs. Using one stem for everything can result in bullets seated crooked, or their noses are deformed or scarred. The latter point isn’t something to be concerned about, but crooked bullets can be an issue.

Also please notice I’ve discussed seating bullets but not crimping. One of the most common mistakes newer handloaders of revolver cartridges make is not crimping or barely crimping bullets. With many propellants, a stout crimp is necessary to “lock” the bullet in place so pressures build to the point where the powder is properly ignited. And, of course, if the revolver has a bit of recoil, a stout crimp is necessary to keep bullets in place. That’s why I consider a proper crimping groove (lead-alloy bullets) or cannelure (jacketed bullets) as mandatory.

I don’t have all the answers to loading “perfect” revolver handloads, but I do know how to make very good ones. It’s simple: Pay attention to the detail.