Reloader's Press

The 6.5 Family of Cartridges

column By: Dave Scovill | June, 19

Since the introduction of the 6.5 Creedmoor in 2008, the pages of Rifle, Handloader and a variety of other hunting/shooting publications have pretty much covered the so-called modern 6.5s. The other 32 or so that came out of Asia, Europe,

One of those was the 6.5x50 Arisaka that was likely the most numerous of the 6.5mm military cartridges, being used by Japan, Russia, U.K., China, North and South Korea, Thailand, Finland and Indonesia. It is the only one of the bunch that I was familiar with in the mid-1950s when my stepfather introduced me to handloading for the 7.7 Arisaka, a war souvenir from his U.S. Navy days in the Pacific. He added that there were two Japanese rifles, the Type 38 and 99, 6.5x50 and 7.7x58, respectively; both were listed in the Lyman-Ideal loading manual in the 1950s.

I killed my first deer with the 7.7mm, but the only 6.5mm I was aware of belonged to another World War II vet who worked for a local logging company. Both rifles were used by the Japanese throughout WW II in various battles in the Pacific Theater, which from what little I learned from U.S. history class and the Encyclopedia Britannica at school, were little more than far-off places on the map of the world.

Twelve years after I learned of the historic naval battles of World War II in history class, we prepared to set the P-3 Orion down on one of the more significant landing strips in the Pacific that was established on Wake Island by Pan American Airways in 1935.

The next morning, Master Chief Petty Officer Hickey and I hustled over to the flag raising, a habit we got into when temporarily

From what was learned from senior U.S. Navy enlisted personnel and officers, the Japanese were ferocious fighters with their 6.5 and 7.7 Arisakas, both being rough copies of the German Mauser. While largely considered “curios” by folks who appeared determined to condemn anything not of .30 caliber and/or made in the U.S., a number of Arisakas went home with returning veterans to serve as suitable hunting rifles.

My stepfather also noted that when he came home to Oregon in 1945 there was nothing to buy, certainly no new cars, and limited fuel and tires for those pre-1941 models like Mom’s 1939 Buick that were still running, and no domestic firearms and/or ammunition had been manufactured for several years. Even a somewhat battle-worn Arisaka was better than nothing, and a beat-up, old Winchester Model 94 carbine was a prize.

The Russians purchased some 600,000 Model 30 and 38 rifles prior to the revolution. Many of those

rifles were stored in Finland. When the Finns recognized a chance for independence from Russia, they grabbed the 6.5x50 rifles stored in Finland and ran the Russians out of the country. (Tour guides in Finland are fond of that story.)

It is worth noting that each time any of the above countries got into a war, 6.5x50 rifles were picked up as “spoils,” and their reputation spread around the globe.

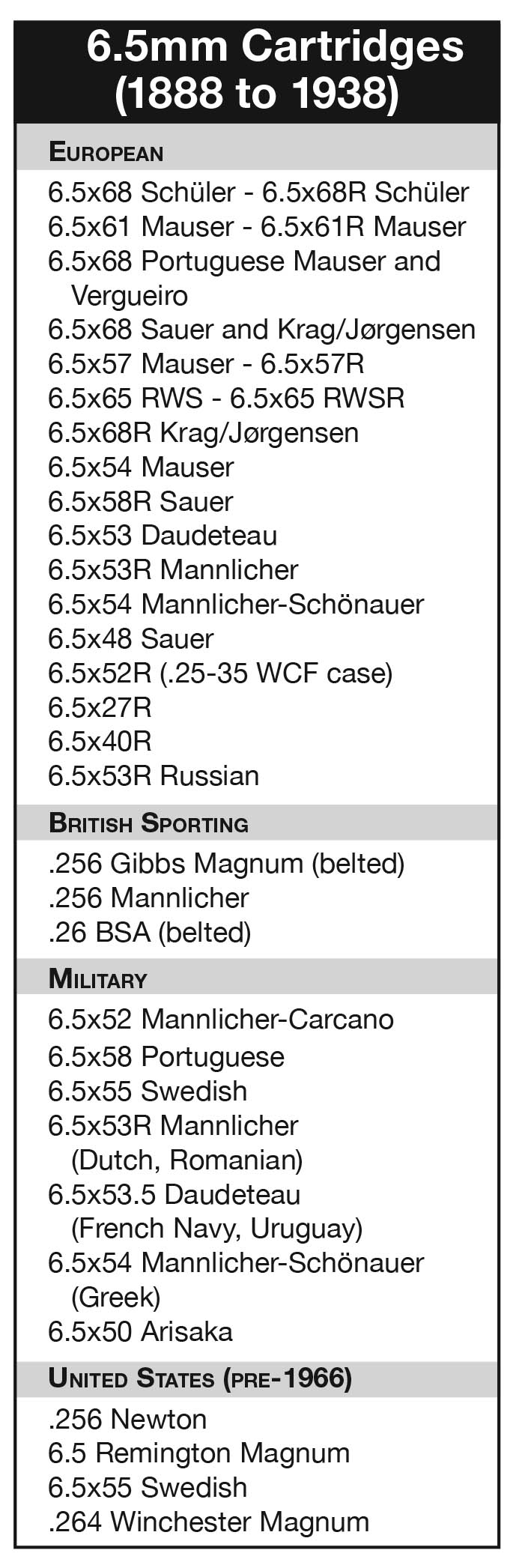

To gain some idea of the number of 6.5mm cartridges prior to WW II, see the accompanying table. Some of the designations are similar, but in most cases (no pun intended) not exactly the same. That might in itself have led some countries to come up with their own cartridge to avoid homeland confusion.

With possible exception, one or two may have been inadvertently left out. For further review, consult Cartridges of the World. It is interesting that the 6.5 Remington Magnum was listed in the 8th edition of Cartridges of the World under “obsolete.”

Currently, newer 6.5s include the .26 Nosler, 6.5-300 Weatherby Magnum, 6.5 PRC, 6.5 Creedmoor, 6.5 Grendel, 6.5-284, .260 Remington, 6.5x47 Lapua, etc., and a bunch of wildcats based on belted and nonbelted brass like the 6.5 STW and 6.5 WSM, respectively.

Many of the pre-World War II cartridges were introduced with 156- to 160-grain roundnose, lead-core bullets, but following the Hague Convention, circa 1899, that outlawed softnose bullets (aka Dum Dum) in warfare, many countries followed the German lead and switched to a lighter, full-metal-jacket spitzer design. In 6.5mm caliber, the standard weight was reduced to 139 grains (plus or minus a few grains), but most, if not all, countries stayed with the original rifling twist rate of approximately 1:8.6 established earlier for heavier roundnose bullets. Owing the current popularity of 6.5mm 140-grain bullets, it is difficult to locate 156- and/or 160-grain roundnose bullets in North America, but they are still listed by Norma and well respected in Europe.

Following World War II, a fair number of 6.5x55 Swedish Mausers and Krags, 6.5x50 Arisaka and 6.5x52 Carcano rifles were imported to the U.S. where they served as inexpensive and quite effective hunting (deer) rifles. In Scandinavia, the 6.5x55 continues to enjoy an excellent reputation as a moose cartridge. Some Arisakas were also converted to other calibers for which ammunition and/or components were available, such as the conversion from 6.5x50 to 6.5x257 Japanese.

In large part, the historical record in this country for war surplus 6.5 rifles was not kind. Most were considered weak when compared to Springfields or Model ’98 Mausers, and folks who considered the .257 Roberts or .270 Winchester ideal for hunting flatly rejected the foreign oddball 6.5mm. When Remington introduced the 6.5 Remington Magnum in 1966 to compete with the .264 Winchester Magnum launched in 1958 in apparent attempts to capitalize on the growing 6.5mm import market, both were summarily dissed in any comparison to the .270 Winchester. The press continuously complained about the particularly odd (short) barrel lengths that cut performance to that of the .256 Newton (circa 1913) on a shortened .30-06 case. Pundits also tagged the .264 as a “barrel burner,” which was pretty much the kiss of death, although the average hunter would never fire a dedicated hunting rifle enough to care.

One of the talking points regarding the 6.5 Remington and .264 Winchester Magnums in the 1950s and ’60s was their long-range capability, owing the ballistic efficiency of the 130- to 140-grain spitzers along with the superior downrange trajectory and energy of the heavier 150- to 160-grain spitzer, semispitzer and roundnose designs over extended ranges that pack more punch when they hit the intended target. Reading between the lines, all that palaver was supposed to add up to improvements over the competition, aka .270 WCF, which was generally considered, with the exception of Elmer Keith and his followers, the “ideal cartridge” for North American big-game hunting. As the saying goes, “fat chance.”

While Remington and Winchester attempted to feature downrange ballistics as the key selling point for their so-called magnum 6.5mm cartridges, the old guard pre-Vietnam) gun press, being somewhat smitten by the .270 WCF, .30-06. .300 H&H, old standbys like the 7x57 Mauser, .257 Roberts and .25-06 and a number of wildcats that delivered similar or somewhat enhanced performance, didn’t buy it. It didn’t help that the 7mm Remington Magnum showed up in 1962 and obliterated any and all of the 6.5 competition.

Some 50 years later, when the new lineup of 6.5mm cartridges was introduced, starting with the .260 Remington, which had been around since 1953 as Ken Waters’ wildcat .263 Express, the “millennial gun press,” either unwilling or too busy to double check the facts against bullets of various calibers with similar sectional density and ballistic coefficients, bought the reincarnated ballistic gobbledygook hook, line and sinker.

Not that any of the above is to suggest that a 6.5mm is better or worse than the competition, but history suggests it makes no sense to butt it up against one of the most popular hunting cartridges/calibers of all time, the .270 Winchester, which if anyone goes to the trouble of looking it up, shoots hunting-weight bullets with some of the most ho-hum BCs on the planet.