.500 Smith & Wesson Magnum (Pet Loads)

Updated Loads

feature By: Brian Pearce | June, 21

Naturally, it was a modern, robust design that featured a five-shot cylinder and was capable of handling powerful, high pressure cartridges. Smith & Wesson worked with COR-BON in the development of the new .500 Smith & Wesson Magnum cartridge, which was capable of pushing a 440-grain cast bullet to 1,625 fps, a 400-grain jacketed softpoint to 1,675 fps, a 350-grain Hornady XTP at 1,725 fps or the 275-grain Barnes XPB at 1,665 fps. While shooting a few rounds is fun and exhilarating, firing full-house 440-grain loads extensively (such as when developing handload data), wherein hundreds of rounds are fired daily, the repeated pounding to the palm of the hand will cause bruising and blisters and is reported to have injured the wrist bones of some shooters.

Nonetheless, the gun received widespread press and was even reviewed in The Wall Street Journal, and sales soared. In the past 18 years the .500 S&W has taken the world’s largest game, and when the correct bullets are used, it has earned an impressive record of one-shot kills. While other handgun manufacturers have offered guns so chambered, the Smith & Wesson is by far the most popular and commonly encountered. Rifle manufacturers have also chambered guns for the .500, with Big Horn Armory offering a high-quality lever action, which is a potent, yet a very handy carbine.

Early ammunition from COR-BON, Hornady and others – as well as cases produced by Starline and Winchester – featured primer pockets for large pistol primers (with magnum versions being used). However, maximum loads often contained spherical powders, which did not ignite properly with large pistol magnum primers. They were known to hangfire, which would cause pressures to soar and is actually a very dangerous combination. In other instances, primers would rupture with leaking gases causing erosion to the firing pin, recoil plate, etc.

Eventually, cases were changed to accept large rifle primers, which better withstood the pressure and alleviated the hangfire problems. The earlier style cases are still often encountered, which should not be used with the accompanying data. Starline cases were used exclusively to develop the accompanying data. They feature an “R” on the headstamp, which indicates that their primer pockets are for rifle primers and differentiates them from cases produced for the large pistol primers.

In preparing this article, it was noted that the strength and hardness of cases varied considerably from different manufacturers. For example, a load that performed perfectly when assembled in one brand of cases would stick cases in the chambers when the identical load was assembled in a different brand of cases. Harder cases tend to stick less to the chamber walls (aka spring back) when compared to softer cases. However, harder cases are more prone to cracking or splitting sooner with multiple reloadings.

It is noteworthy that the big Smith & Wesson Model 500 revolver has been accused of “doubling,” or firing twice, when the trigger is pulled just once. This is a shooter error and not an issue with the gun. How it happens is that when the shooter fires the gun (usually with full-house heavy bullet loads), the trigger is allowed to rebound during recoil, which in part is caused by the gun moving backward authoritatively in the hand during recoil. While the gun is still in full recoil, the shooter is squeezing the revolver firmly just to hang onto it. Unfortunately, the trigger finger is likewise being squeezed, which causes the revolver to fire a second time in the double-action mode, usually with the barrel pointed upward. For shooters just wanting to try the big .500 for fun, a good solution is to just load one cartridge in the gun at a time.

When loading full-house loads that more or less duplicate factory loads, cases should not be reloaded more than two or three times, maximum. Full-house loads tend to cause primer pockets to loosen and cases lose some of their ability to hold the crimp.

Currently, factory loads are offered by Hornady, Federal, Winchester, Buffalo Bore and others. Most are full-house loads and generate pressures between 53,000 to 57,000 psi, or around five to 12 percent below industry maximum average pressure. For reference purposes, the accompanying table lists popular factory load stated velocities. Those that were available at press time were checked for velocity in the test gun; however, due to the huge ammunition backorder situation, some loads were not available for testing.

Most of the accompanying load data has been pressure tested, but not all. Nonetheless, based on experience and predictable factors, I believe that all data is within industry pressure guidelines.

RCBS carbide dies were used to develop the accompanying test data, with the carbide sizer die saving considerable time as cases do not need lube. Reloaded cases should be full-length sized to assure reliable chambering, while new cases should be sized to assure correct chambering, but this also serves to obtain proper bullet and neck tension. The RCBS expander ball measures .4945 inch; however, a second expander ball was obtained and turned down to .4925 inch in diameter, which increased bullet and case neck tension. This allowed some experimenting to determine if this minor change would lower extreme velocity spreads and help prevent bullets from “walking,” or creeping out of the case when subjected to repeated recoil of full-house loads. While my experiments were less than conclusive, they certainly indicate that the smaller expander ball offers some advantage.

As indicated, large rifle primers are specified to obtain proper powder ignition, prevent hangfires and prevent primer cups from rupturing with full pressure loads. Some sources suggest using a large rifle magnum primer; however, even the largest powder charges containing slow burning revolver powders are almost always below 50.0 grains, and usually between 35.0 to 45.0 grains. There might be some bullet and powder combinations, or circumstances (such as extreme cold weather) that benefit from the use of a magnum primer. However, in my testing, standard large rifle primers provided enough heat to obtain reliable ignition with all loads. The CCI BR-2 primer was

selected to develop the accompanying data. Federal 210, Winchester WLR and Remington 9½ primers can be substituted. While there will be some changes with pressures and velocities, indications are that the change will not alter loads to any important degree. However, if magnum primers are substituted, pressures will increase, and it may be necessary to reduce powder charges.

The .500 S&W is a natural cartridge for use with cast bullets. If the correct bullet, alloy and design are selected, they will produce equal accuracy with jacketed bullets and big-game hunters appreciate their deep penetration qualities. Furthermore, they are ideal for loads with muzzle velocities below 1,000 fps, but they can also be pushed to nearly 1,900 fps with good accuracy.

Generally, cast bullets should be sized to .501 inch, which corresponds perfectly with most revolver’s throats that measure .499 to .500 inch, while the groove diameters generally measure more or less the same. This results in a proper gas seal that serves to minimize fusion and fouling. If cast bullets are to be used in conjunction with full-house loads, they should be cast with at least a Brinell Hardness Number (BHN) of 16, which will help them to properly “hold” the rifling. It should be noted that Smith & Wesson Model 500 revolvers feature EDM rifling, which lacks the beautiful, mirror shiny finish found on pre-1998 to 2000 Smith & Wesson revolvers. As a result, many barrels are prone to leading. While performing either a barrel break-in procedure or fire lapping will help, generally the best solution is to use a cast bullet featuring a gas check and lubed with a high viscosity bullet lube.

.jpg)

Moving on to jacketed bullets and copper monolithic versions, the selection of bullets designed specifically for the .500 Smith & Wesson is good. For example, Hornady offers a 300-grain FTX, a 350-grain XTP-MAG and a 500-grain XTP-FP. Speer offers its 350-grain Deep Curl softpoint, while Sierra offers a 350-grain JHP and 400-grain JSP. Barnes offers its expanding monolithic XPB bullets in 275-, 325- and 375-grain weights. All of the above bullets feature a deep crimp groove or cannelure to accommodate a roll crimp or neckdown crimp. While bullets designed for the .50 Action Express are of correct diameter, they lack a proper crimp groove and their construction is insufficient for the pressures associated with the .500 S&W and should not be used.

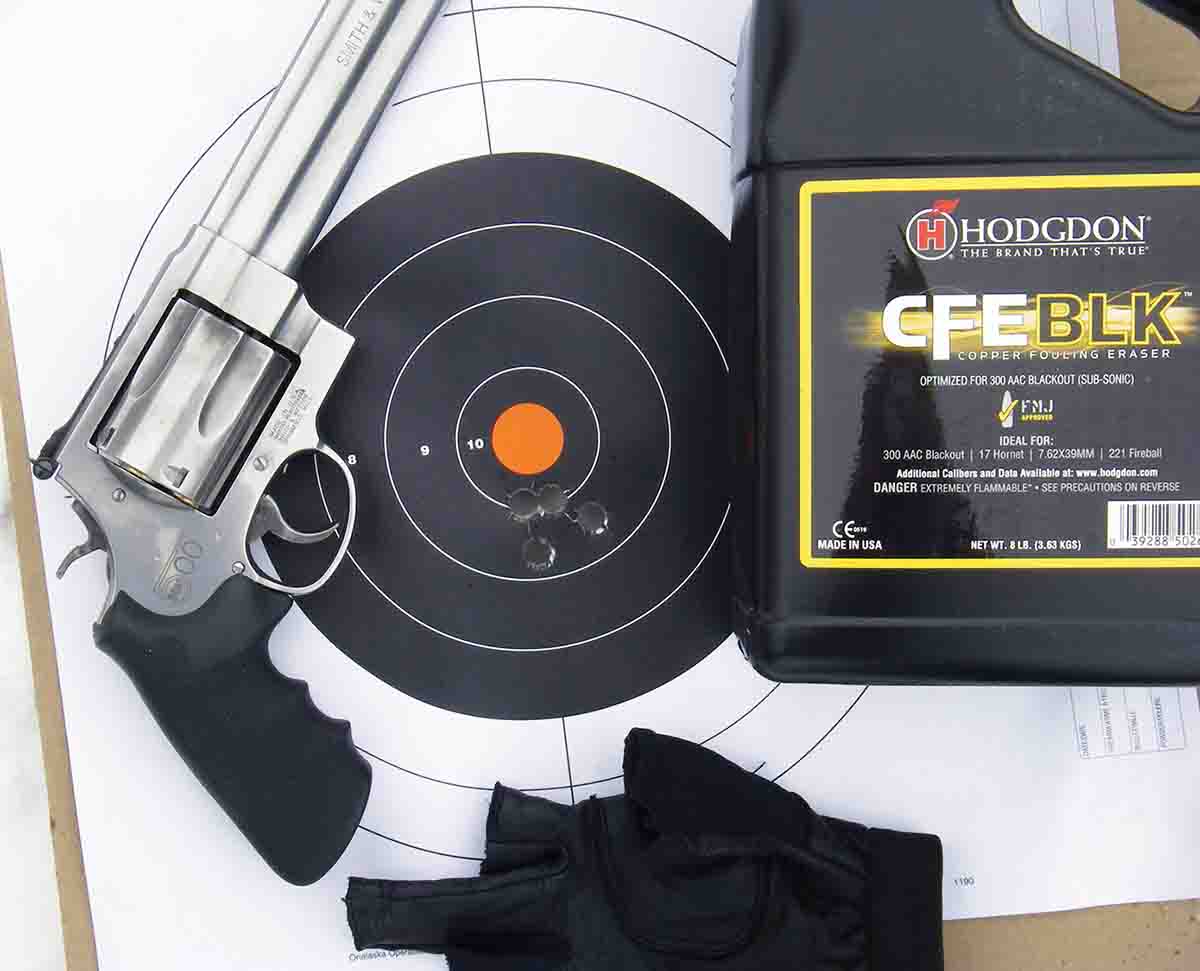

For full-house loads, top performing powders included Hodgdon H-110 (which is the same powder as Winchester W-296), CFE BLK, Lil’Gun, Accurate No. 9, No. 11FS, Alliant Power Pro 300-MP, 2400 and Ramshot Enforcer. For reduced or midrange loads, notable powders include Hodgdon Titegroup, Accurate No. 2 and IMR-4227 (primarily with starting loads). Hodgdon Trail Boss is really a top powder for light loads that are under 1,000 fps with cast bullets, as it bulks up in the case and offers very consistent velocities and pressures. It should be noted that the .500’s huge case capacity makes it difficult to develop light loads that offer respectable extreme spreads and accuracy, while not being prone to hangfires or erratic ignition. When loaded with common revolver powders that are typically used in light loads, most will only take up a small portion of the huge case capacity, which can be a very dangerous situation. This feature limits suitable load data. Incidentally, suggested start loads should not be reduced.

Considering the cost of .500 S&W factory loads and the fact that ammunition is scarce, handloading for this cartridge is more practical than ever. Furthermore, its versatility and usefulness can be hugely increased.

.jpg)

.jpg)