A Colt Quartet

.38 Long Colt, .41 Long Colt, .44 Colt and .45 Colt

feature By: Mike Venturino | June, 21

The .44 and .45 Colts were introduced, respectively, with 1.10-inch and 1.285-inch case lengths. Those never changed. However, .38 and .41 Colts were first introduced in “short” versions that segued into “long” ones. By the late 1800s, both .38 and .41 Colt cases were lengthened to 1.03 and 1.13 inches. Having owned many revolvers for both, I’ve yet to encounter one with “Long” in the caliber stamp. The reason for this lengthening of their cartridge cases will be returned to shortly.

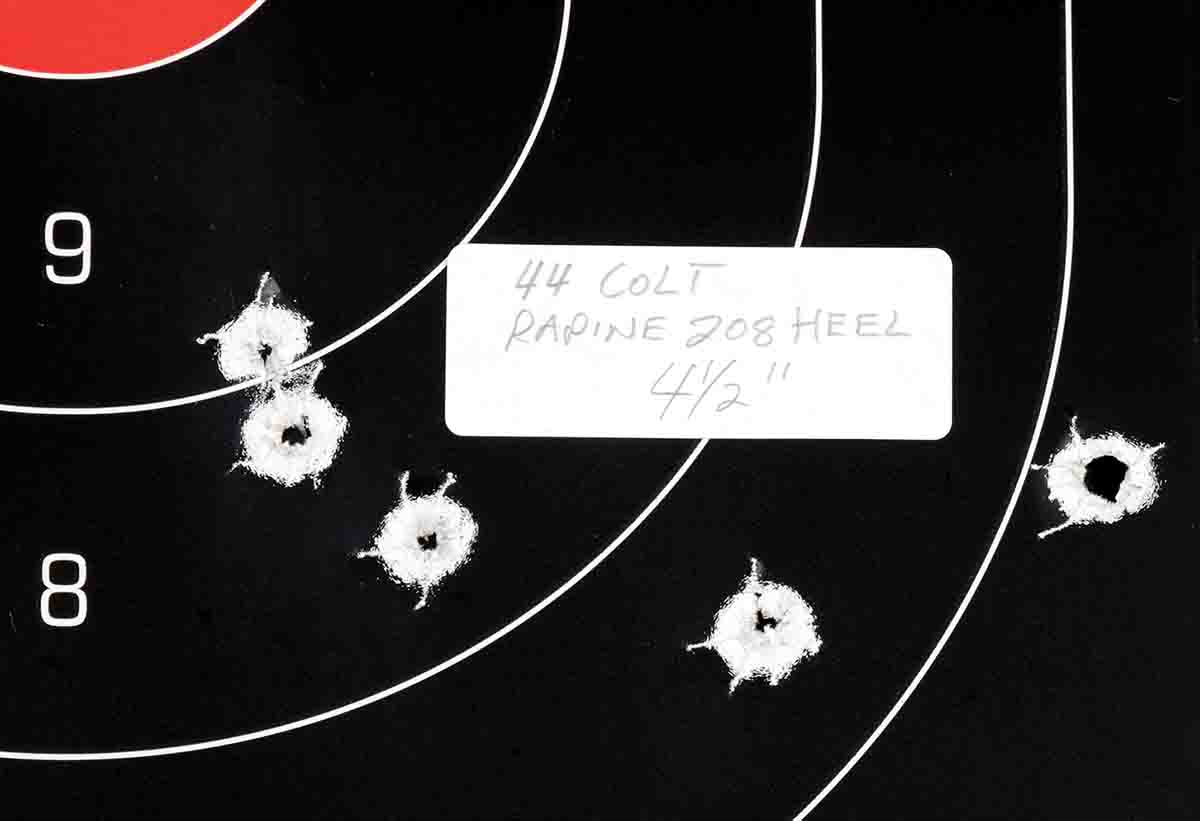

Arriving first in 1871 was the .44 Colt, with its handgun being Colt’s Richards Conversions, which were combinations of .44 Model 1860 cap-and-ball-parts, with some of new manufacture. Bullets for .44 Colt bullets were heel-type, meaning they had a reduced diameter shank that fit inside the cartridge case. Above was a larger diameter that was the same as the outside of the cartridge case and more or less the same size as the barrel groove diameters. Usually, bullet lubricant was carried in grooves on the main diameter of the bullet, where it was exposed to the environment.

Take note here that Italian made .44 Colt revolver replica barrels are not true to originals. They are made to accept modern .429/.430-inch bullets. That turns the difficult-to-handload original .44 Colt into a handloading pussycat.

In the 1990s, after acquiring a Colt Richards Conversion, I was given a box of original UMC factory loads. Strangely, they had no groove(s) for outside lube, so I pulled one apart. Beneath its bullet was a 1⁄8-inch thick beeswax wad, under which set a .030-inch thick cardboard disk and finally, a 21-grain black-powder charge. The bullet was of very soft lead, weighed 208 grains and measured .449 inch at its widest.

Colt’s next cartridge has been its all-time best, and of course, not much can be said about it that hasn’t already been said by myself and many other writers. That’s the .45 Colt, adopted in 1873 by our government along with the revolutionary new “Strap” revolver, as Colt executives first termed it in letters to government ordnance officers. Now it’s the Single Action Army. Many of today’s .45 Colt fans have been misled into thinking the original military ammunition for .45 Colt carried 40 grains of black powder and 255-grain bullets. Test loads perhaps did, but military issue loads had 30 grains under 250- grain bullets. Some commercial loads later became more powerful. For instance, Winchester cataloged a 38-grain charge in 1899 and a 1917 U.S. Cartridge Company catalog lists 37 grains with 250-grain bullets.

As said, case length for the new .45 cartridge was 1.285 inches. That was very long for the 1870s and set the stage for the twentieth-century’s .44 Remington Magnum. (Thirty Carbine, .357 and .41 Magnums are very close at 1.29 inches.) Also, new for a Colt cartridge was a bullet with its full diameter setting inside the cartridge case. That covered grease grooves, protecting them from the elements.

Colt cartridge designers must have been a stubborn lot. Even after the obvious benefit of bullets with full diameters inside cartridge cases as shown by the .44 S&W Russian, .45 S&W Schofield and Colt’s own .45, it continued to introduce new rounds with heel-base bullets in the mid-to-late 1870s. Prime among them were the .38 Colt and .41 Colt.

Towards the end of the nineteenth-century, someone involved with cartridge design wised up. Instead of having those infernal heel-base bullets with their dirt catching, exposed lube grooves, the decision was made to lengthen cases and stick bullets inside them, as with the .45 Colt. Great idea, except then bullets could only be about .35 inch (for .38s) and .38 inch (for .41s) in diameter, and they would be fired in barrels with groove diameters of .375 and .400 inch. With original .38 and .41 Colt revolvers, .357-inch and .386-inch bullets can be dropped through their barrels without touching steel. (Later in the twentieth-century, Colt did reduce barrel groove diameter for .38 Colt to .354, which remained their dimension for .38 Special/.357 Magnum barrels throughout that century.)

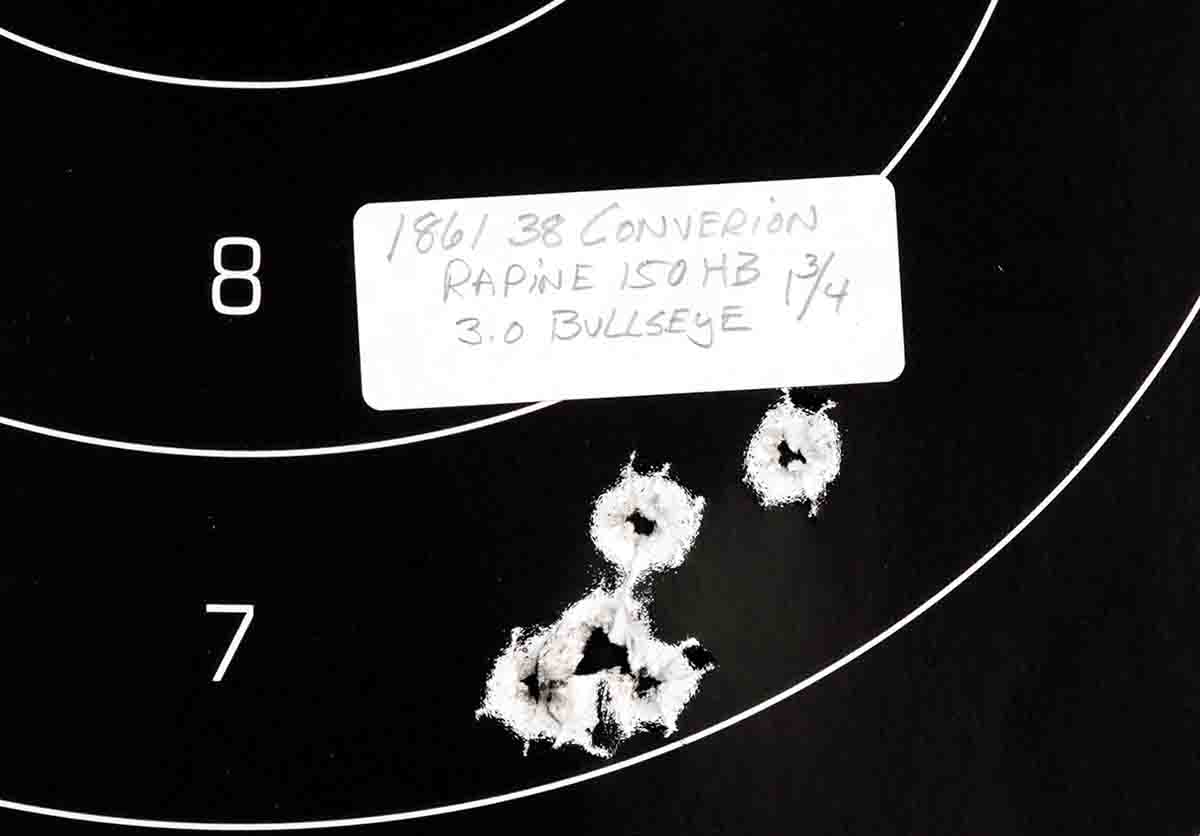

The remedy for the small bullet/big-bore problem had been around since the 1840s, courtesy of a French army captain named Minié. Those were pure lead, hollowbase Minié balls made famous in the carnage of the American Civil War of 1861-1865. The miracle isn’t that hollowbase .357-inch and .386-inch bullets solved the problem with .38 and .41 Colt factory ammunition, it’s that they work so well. Cartridge case lengths were increased to 1.03 inches for the .38 Long Colt and 1.13 inches for .41 Long Colt. Those factory rounds contained, depending on manufacturer, about 19 grains black powder with 150-grain bullets for .38 LC and 21 grains for the .41 LC with 200-grain bullets.

In my collection is a modern conversion of a 2nd Generation Colt Model 1861 made to fire .38 Long Colt. I asked the gunsmith who “converted” it to leave the traditional large bore. As said, I have little use for heel-base bullets: all my .38 LC handloads are assembled with hollowbase bullets.

Recently, I decided to get back into .41 Colt reloading because of my purchase of a fine 1902 vintage Colt SAA. However, unwisely I had sold all my .41 Colt reloading equipment a dozen years ago. Starline makes .41 Long Colt brass so that’s a no-brainer. However, Lyman’s only .41 LC bullet mould of yesteryear, No. 386178, is very rare, and as was said earlier, Rapine is out of business. A fellow .41 handloader who does have both Rapine and Lyman hollowbase moulds sent me 50 of each to try in my new SAA.

Perusing the internet in hunting for my own .41 HB mould, I found a reference to an outfit named MP Molds. A visit to its website showed the company actually had 200-grain, hollowbase .41 Colt moulds in stock. To my great surprise, when I paid for it by credit card there was an option for Euros or U.S. dollars. That’s when I discovered MP Molds is located in Slovenia! Even more amazing was that my new brass, double cavity, hollowbase .41 LC mould arrived in only five days with shipping included in the purchase price. Also included in the price was a top punch for Lyman and RCBS lube/sizing machines.

A word about bullet alloy temper is necessary. With regular “solid” bullets, my oft-used 1:20 (tin-to-lead) mix suffices. However, hollowbase bullets must be even softer. With them alloy is 1:40 (tin-to-lead) and their skirts definitely swell to engage rifling in those oversized .38 and .41 Colt barrels as shown by recovered bullets. I feared some problems with lead fouling but was pleased to find both .38 and .41 barrels free of it after firing a couple of hundred rounds each.

Except in some instances for the .45 Colt, my handloading advice for the “Quartet” is to be gentle. Of course, in original .44 Colt Conversions, if they are fired at all, do it with black powder. With smokeless powder loads in the others, if the revolvers are from the smokeless powder era, I set my goal to only approximate factory load ballistics.

Luckily, I have some original .38 LC and .41 LC factory loads to judge by, and .45 Colt information is common.

In recent years I’ve touted Hodgdon’s Trail Boss powder as my pick for reloading revolver cartridges originally meant for black powder. However, I cannot say that about loading hollowbase bullets in .38 and .41 Long Colt cases. I’ve had great difficulty in getting it to ignite properly, with velocity variations being sometimes hundreds of feet per second (fps) in a five-shot string. My theory is that the effort to swell the hollowbase bullet skirts uses up energy that would promote better ignition. As evidence of such, some shooting was done using the same .38 LC handloads with 150-grain Rapine HB bullets in two revolvers. One was the Model 1861 conversion featured here and the other was a 5½-inch Colt SAA .38 Special. Those handloads gave higher velocities from the .38 Special despite its 2-inch shorter barrel.

As I’ve grown older, it seems that my tastes in revolver cartridges have gravitated toward the older rounds. Nowadays, there is no need for magnums in my shooting, and the oldies such as “Colt’s Quartet” are far easier on hands and ears.

.jpg)