Rifle Case Necks

Technical Details of "Bottlenecked" Brass

feature By: John Barsness | June, 21

The unburned portion results in white smoke blown out the muzzle and heavy black fouling inside the barrel. Bore fouling built up much quicker and thicker when large cases were necked down to smaller bores, the reason truly smallbore black-powder cartridges had relatively small cases, especially when bottlenecked. The .25-20 Winchester is a prime example.

Really bottlenecked rifle cases didn’t arrive until the development of practical smokeless powder for rifles. The first appeared in 1884, the cartridge that eventually became generally known as the 8x57 Mauser. However, one semi-exception was the .303 British.

In the late 1880s, Great Britain had started developing a smokeless rifle propellant, but what eventually became cordite needed more work. Meanwhile, other major European armies were switching to bolt-action repeaters, so Britain went ahead and introduced the bolt-action Lee-Metford rifle in 1888 – but instead of smokeless powder, it used a heavily compressed charge of black powder, supposedly getting around 1,800 feet per second (fps) with a 215-grain bullet.

The “Lee” portion of the rifle’s name referred to the action, designed by James Paris Lee, while “Metford” referred to the shallow, polygonal rifling, designed to minimize black-powder fouling. When they switched the propellant to cordite a few years later, the hotter gas quickly washed out Metford rifling. The Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield then developed a deeper, sharper rifling pattern, and in 1895 the rifle became the Lee-Enfield.

The first smokeless, bottleneck American cartridge appeared when the U.S. Army adopted the Springfield Model 1892 rifle, based on the Krag-Jorgensen bolt action developed in Norway. The new cartridge was called the .30 U.S. or .30 Army, and strongly resembled the .303 British, except for a much longer neck.

Some handloaders considered the .30-40 a particularly well designed round, partly because of the long neck. Many riflemen back then (and some even now) considered short necks a ballistic abomination because longer bullets could “protrude” into the body of a bottleneck cartridge, taking up powder space and theoretically reducing potential muzzle velocity.

The long neck also worked well with a wide range of bullet weights, from 150-grain spitzers to 220-grain roundnose bullets, important back when all expanding hunting bullets were “cup and cores,” made by swaging a harder metal jacket around a lead-alloy core. One early American handloading authority, Townsend Whelen, often mentioned the virtues of the .30-40’s long neck.

Despite those opinions, case necks soon became shorter. A good example is the 9.3x62 Mauser, designed in 1905 by Otto Bock to function in the standard 3.30-inch magazine of the K98 Mauser. The 9.3x62 provided settlers in Germany’s African colonies an affordable rifle powerful enough to handle the large “varmints” eating their cattle or crops, from lions to elephants.

To increase powder capacity, Bock increased the diameter of the 8x57 case slightly and moved the shoulder forward, shortening the neck. The original “African” load featured softnose and full metal jacket 18.5-gram (285/286 grain) bullets at around 2,150 fps, which worked so well the 9.3x62 remains popular, especially since modern powders have increased the standard factory velocity to 2,360 fps.

Shorter necks became more common after that, despite the bases of heavier bullets ending up far below the neck. Another early example was the .300 Savage, introduced in 1920 to approximate the original ballistics of the .30-06 by using improved post-World War I powders, yet fit in the Savage 99’s short rotary magazine. Despite the .300’s short-necked, stumpy case, the powder capacity almost matched the .303 British and .30-40 Krag.

Of course, many traditionalists whined about the short neck and “deep-seated” bullets, but as early Handloader columnist Bob Hagel pointed out, the bases of the bullets were surrounded by extra powder, which wouldn’t be there if the neck was longer and the case shorter.

During the post-World War II era, many short-necked cartridges continued to appear, and traditionalists continued to complain, often suggesting the new rounds should be chambered in rifles with longer magazines, so bullets could be seated out “properly” to increase powder capacity. The problem with that theory is seating relatively small-caliber bullets out further doesn’t result in enough extra powder capacity to make much difference, because the gain in powder room only results in about a quarter as much extra velocity.

However, even Hagel fell for this argument at least once, having a .284 Winchester built on a 1903 Springfield action. This did result in considerable extra velocity, though mostly because Hagel was a real hot rod handloader.

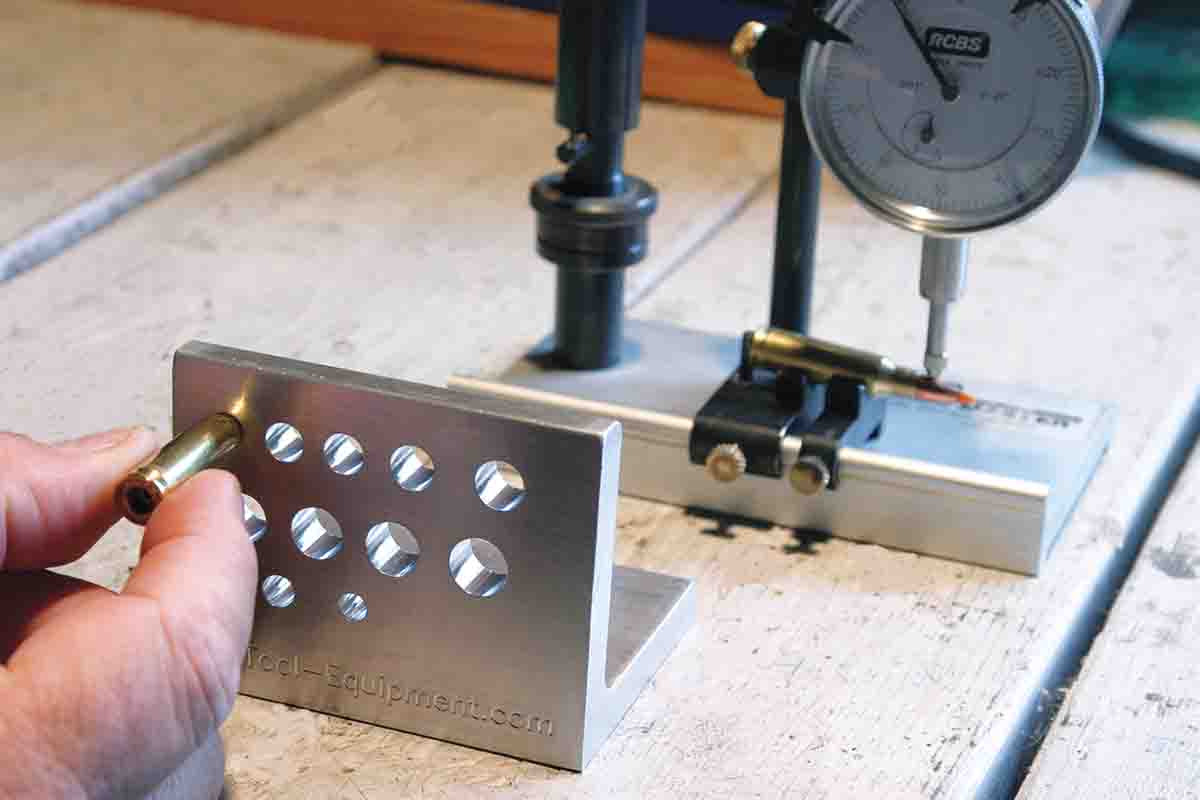

However, short necks do not “cure” one of the basic accuracy problems encountered by handloaders. Somebody once called the neck the “steering wheel” of bottlenecked cartridges: If the neck isn’t aligned with the case body, then the bullet starts down the bore a little crooked. Luckily, many of today’s sizing dies can prevent this – and even if loaded rounds are slightly misaligned, there are tools to correct the alignment.

This short-neck trend continues today, with both “beltless” magnums and smaller, more efficient cartridges, but during the same period, other case-neck factors came to light. One arose when benchrest competition became popular: For the finest accuracy, case necks should be as close to the same thickness as possible. If neck thickness varies from side to side, the bullet ends up off-center compared to the case body and chamber throat.

It took a while, however, for benchrest shooters to start lathe-turning necks to even thickness. Apparently, nobody did it much early on. The 1951 Bench Rest Shooters Association Manual, The Ultimate in Rifle Precision, was edited and partly written by Townsend Whelen. It contains chapters by various experts of the day, including Harvey Donaldson, inventor of the .219 Donaldson Wasp, and “M.H. Walker,” the Remington engineer Mike Walker who, among other accuracy improvements, designed the .222 Remington cartridge. Nobody mentions lathe-turning necks. Instead, Whelen discussed selecting accurate cases by weight-sorting and test-shooting.

Even after benchresters started neck-turning cases a few years later, another problem sometimes appeared, popularly termed the “dreaded donut,” a ring of thicker brass around the base of the neck. This appears for a couple of reasons, and I first encountered the most common in 1974 with the second rifle I handloaded for, a Remington 700 BDL in .243 Winchester purchased in 1974.

It shot very well at first, but after the Winchester cases had been reloaded a few times, “fliers” started showing up, and eventually occasional signs of high pressure. I measured the cases frequently, trimming when they approached maximum length, so that wasn’t the problem.

Instead, repeated full-length resizing and firing had pushed the upper end of the 20-degree shoulder into the bottom of the neck. This was diagnosed by a handloading trick mentioned in an old Dean Grennell article: Insert a bullet’s base into the neck of a fired case. If it won’t slide in easily, then the neck has thickened so much that chambering a round essentially crimps the brass around the bullet, resulting in erratic pressures and velocities.

I tested my fired .243 cases, and lo and behold, the bullet hung up in varying degrees at the base of the neck. An inside neck-reamer for my Forster case trimmer cured the problem.

.jpg)

I also had an abundant supply of new .270 Winchester cases, so I necked some down. This required trimming the longer necks, but accuracy immediately improved. Eventually, I decided that if I ever built another 6.5-06, it would actually be a 6.5-.270, not just to save trimming time, but to lengthen bore life. Most bore erosion occurs right in front of the case mouth, where powder gas is hottest, and longer necks protect more of this area.

After running into the “firing donut” a few more times I decided to try an alternative cure, described in a short essay appropriately titled The Dreaded Donut, from another book collection of accuracy tips by various people, The Benchrest Shooting Primer. The author was Fred Sinclair, the well-known bench shooter and loading-tool maker, who discussed two methods for dealing with donuts, reaming and outside-turning the shoulder/neck junction on cases resized in a typical expander ball die. The expander ball presses the thicker donut-brass outward, where it can be lathed off.

Sinclair claimed outside turning didn’t work as well, because the donut tended to spring back some after the passage of the expander ball. However, I was wrestling with a few donuts in a new 6.5 PRC built on a Remington 700 action with a Lilja 1:8 barrel by Kentucky Gunsmith Charlie Sisk. I expected it to shoot well, but after a few firings of the excellent Hornady brass (which has such an even neck thickness, it didn’t need to be turned) the same symptoms showed up in my .243 and were confirmed by another bullet test.

I didn’t feel like ordering a reamer, so I tried the resizing/lathe method – but first I annealed the necks, resulting in less spring back after resizing, and it worked very well. The rifle started grouping five shots (not just three) in less than half an inch. This won’t win benchrest matches, but is more than good enough for a hunting rifle weighing under 8 pounds scoped.

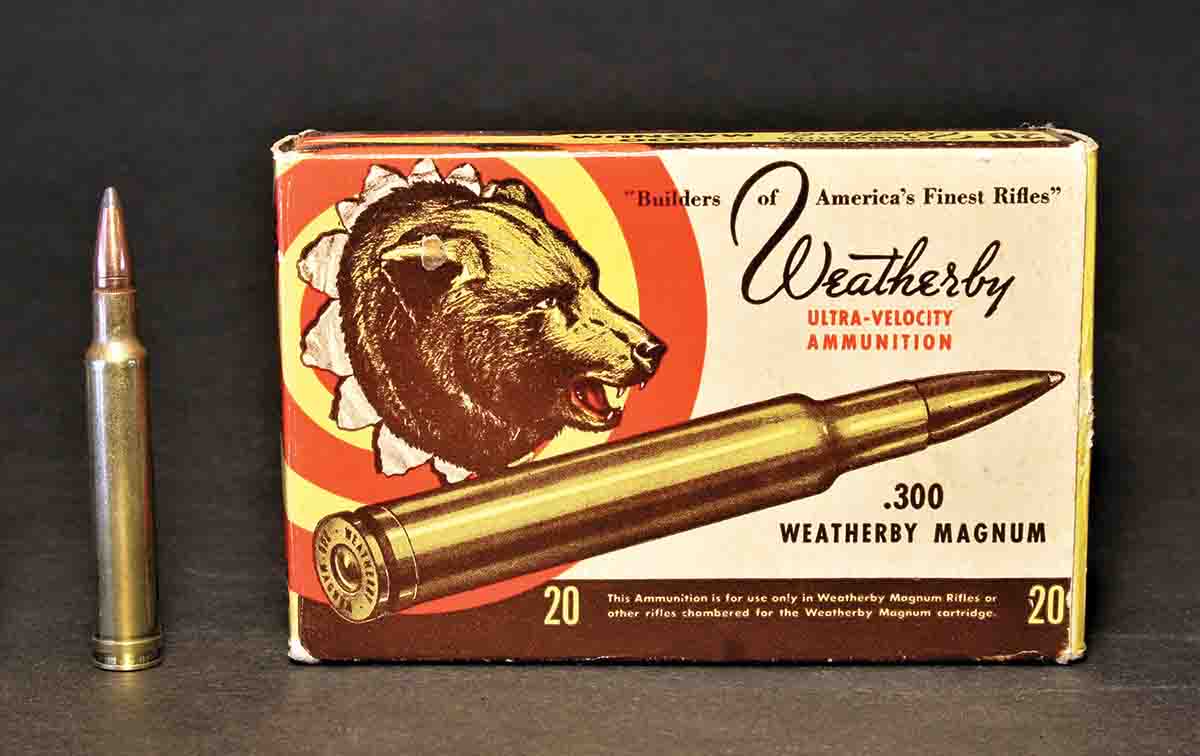

Annealing necks regularly also tends to result in finer accuracy, due to more consistent neck tension on seated bullets. In fact, many benchrest and other target shooters anneal their cases after every firing. After considerable experimentation, however, I have never found any advantage in annealing hunting brass that often, even in super-accurate custom rifles like the Sisk 6.5 PRC or my New Ultra Light Arms .257 Weatherby Magnum.

For those rifles I anneal cases after every four firings, but separate the brass into “lots,” depending on how many times they’re fired. Once-fired brass goes into a labeled Ziploc bag, twice-fired brass into another bag, etc. When loading a box of ammunition, I use cases from the same bag, and when they all end up in 4-times-fired bag, I anneal the entire batch. (This may seem obsessive-compulsive, but hey, what fun would handloading be without some OCD?)

Another trend harkens back to the semi-worship of long necks more than a century ago. Quite a few “modern” rounds with longer necks and relatively short bodies avoid the dreaded donut entirely because a seated bullet’s butt doesn’t encounter the shoulder/neck junction. Among them are the all-time most popular cartridges for short-range benchrest shooting, the .222 Remington and its successor, the 6mm PPC.

The standard Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) overall length for both cartridges is long enough for popular bullet weights in each cartridge to be seated without ever encountering a donut, though the leeway is a little greater in the 6mm PPC. As an example, the bullet I’ve started using lately in my bench rifle (due to Berger discontinuing its 65-grain Boat Tail Target) is the Berger 68-grain Flat Base Target. The base ends up about .03 inch from the shoulder/neck junction.

One other recent 6mm accuracy cartridge, David Tubb’s 6XC, was designed to avoid the donut even when using heavy target bullets in fast-twist barrels. Tubb used the .22-250 as the parent case, shoving the shoulder back to lengthen the neck, then blowing out the shoulder to the “accuracy” 30-degree angle. As a result, even long, high-ballistic coefficient (BC) boat-tails can be seated above the shoulder/neck angle.

Of course, very long boat-tails also help avoid the donut, because the full diameter bullet shank is generally .18 to .22 inch in front of the bullet’s rear end. This is why the new .300 PRC cartridge allows high-BC bullets up to around 210 grains to be seated donut-free – thanks to a combination of a fairly long neck, short body and generous overall length of 3.700 inches.

This longer-neck/shorter-body is of course what Townsend Whelen admired about the .30-40 Krag, though the Krag’s shoulder/neck junction is so gentle it would be extremely unlikely to develop donuts!