Mannlicher's Bundle of Trouble

Still, the 9x56 M-S is Too Good Not to Shoot

feature By: Terry Wieland | June, 21

The 9x56 M-S was the second of four in the early series of rimless cartridges introduced by Steyr-Mannlicher. First came the 6.5x54 (1903), then the 9x56 (1905), 8x56 (1908) and finally the 9.5x57 in 1910. They were chambered, in order, in the Models 1903, 1905, 1908 and 1910, which makes it easy to keep track of which is which. That, alas, is about the only easy thing about them.

The Mannlicher cartridges closely resemble the Mauser line that appeared during the same period. Mausers proved more popular since they were chambered by other gunmakers using Mauser actions; as a result, both brass and ammunition is more readily available today. If they were interchangeable with the Mannlicher cartridges, all would be rosy. Except, they are not supposed to be. Except, sometimes they are. Which can make life exceedingly confusing.

In the 9x56 M-S and 9x57 Mauser, the dimensional differences are so slight as to be invisible to the naked eye. The Mauser is a millimeter wider at the base and a millimeter longer in overall length, but its body is a millimeter or two shorter, which places the Mannlicher shoulder farther forward. In theory, this should mean that it cannot chamber in a 9x57 rifle (but sometimes it can) while the 9x57 should not chamber in a 9x56, except – you guessed it – sometimes it can, too.

In the 1930s, Remington produced hybrid 9x56/9x57 ammunition that was supposed to work in either. It accomplished this seeming impossibility by adopting all the minimum dimensions and keeping pressures exceedingly low. How well it actually worked is anyone’s guess, but at least it provided usable brass for handloaders.

Last year, I acquired a Mannlicher Model 1905 and set about finding ammunition for it. Fortunately, Quality Cartridge now offers brass and Redding stocks dies. Alas, Quality’s brass will not chamber in my rifle, even after being run through the full-length die. This suggests that my chamber is exceedingly tight, to the point of not meeting CIP specifications, because as far as I can tell, the Quality Cartridge brass is dimensionally perfect. To add to the merriment, Quality Cartridge 8x56 M-S brass chambers in it perfectly, but I did not have enough to neck up for this little project.

Fortunately, I have a good supply of reworked 8x56 M-S brass fashioned by Bob Hayley a decade ago for my Model 1908. It necks up easily and works just fine. I also had some 9x57 brass that I had made from new Norma 9.3x57 brass. Guess what? Both the 9x57 and unaltered 9.3x57 brass will chamber easily. The only thing the rifle stubbornly refuses to accept is brass specifically made for it.

In the 1980s, in Rifle No. 86 (March-April 1983), John Van Marter wrote a report on the 9x56 M-S. He experienced almost exactly the same anomalies with brass that I did, finding that 9x57 chambered like it was made for it.

Now bullets. Ken Waters found that his bore measured a maximum of .353 inch; mine slugs at .3525. This pretty much rules out the use of standard .358-inch bullets, but I found five others that offered potential: three from Hornady (InterLock 170-grain, .355-inch Spire Points, 165-grain, .355-inch FTX and 125-grain HAP), as well as Prvi Partizan (Graf & Sons) 180-grain .352 roundnose bullets intended for the .351 Winchester Self-Loading cartridge, and Berry’s plated 124-grain hollowpoints (.356) made for the 9mm Luger.

I also obtained some .356-inch, 200- and 250-grain spire points from Buffalo Arms and tried them in the preliminary testing. Of five identical rounds, two had flattened primers and stiff bolt lifts while the other three were quite mild, and the extreme spread in velocity was an astonishing 445 fps. The excess-pressure signs were disquieting, and I abandoned the effort.

The original 9x56 M-S factory load fired a 205-grain bullet at 2,114 feet per second (fps), which is almost identical to the .35 Remington. As Waters discovered, the 9x56 can be juiced up 100 to 200 fps from the .35 Remington level, and has the added advantage of using a spitzer bullet. This becomes a real asset when you drop down to a 170-grain bullet.

Given all of the above, could it have been chambered for the 9x57 Mauser instead of the 9x56? There is no indication the barrel has been altered in any way, and if it was opened up to accept the 9x57, then standard 9x56 should still chamber in it. All of these are questions that can never be answered since the Russians seized the Steyr records in 1945. All we are left with is conjecture, and a sweet little rifle that is a pleasure to carry and a joy to shoot, hybrid though it must be.

One of the tricky things about shooting any of the early Mannlicher-Schönauers is that the spool magazines were sculpted to fit one cartridge and bullet combination, and no other. Switch a 1903 (6.5x54 M-S) magazine with a 1908 (8x56 M-S) and it will probably work poorly at best. The 1905 was intended for a 205-grain roundnose bullet, not a 170-grain spire point. Fortunately, this turned out not to be a problem, unlike my 1903, which stubbornly insists on long, roundnose 140- to 160-grain bullets, or it won’t feed at all.

With some rifles, you search for the best combination of bullet weight, velocity and accuracy to create the optimum hunting or target load; with others, you end up desperately seeking anything – anything – that works. My 1905 is one of the latter.

Beautifully made and finished though they are, the entire series of early Mannlicher sporting rifles – in my experience and, apparently, in Ken Waters’ as well – need to be treated as individuals. Unlike buying a car, where you fill it with gas and drive away, these are more like horses. Until you saddle up and climb aboard, you are not sure how they will react or what they require. Accordingly, creating ammunition is something that must be approached cautiously, with an eye to getting a few reasonable loads that provide the performance you want.

The two Hornady bullets are almost ideal. Presumably, the 170 grain is intended for the .350 Legend, and the 165-grain Flex-Tip for the .35 Remington in a tubular magazine, but both work just fine in my Mannlicher 1905.

Another bullet that could be useful is any 147-grain, solid or hollowpoint, made for the 9mm, but they were also unobtainable. And yes, I tried both begging and bribery. Acquaintances who had any in their secret stashes were demanding an inordinate ransom in primers, which are even harder to come by. Thanks, but no.

Fortunately, I have a good supply of Hornady 125-grain hollowpoints made for 9mm pistol cartridges. Because the bullet measures .356 inch, I wanted to keep pressures down, and loaded it light. Exactly what you would use a 125-grain hollowpoint for, in a rifle like this, I really have no idea. Rampant possums? Raccoons in the corn? Clays tossed on a dirt bank? Whatever you might decide, through some quirk of fate the combination of these bullets, with IMR Trail Boss, delivered a load that is dead accurate at 50 yards, shooting right where the sights are aligned, with almost no recoil.

The .352-inch, 180-grain Graf & Sons solid proved to be so erratic that I abandoned it early on. Velocities were low and varied, and accuracy was nonexistent.

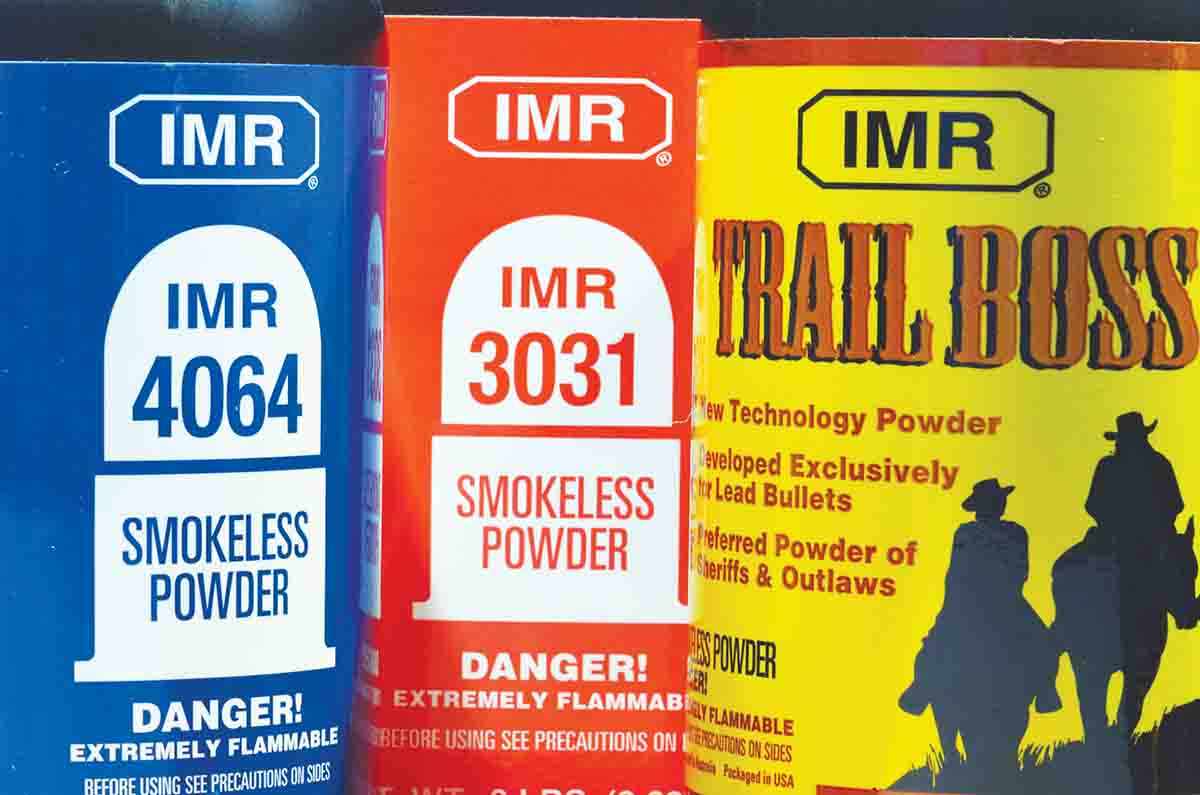

This left the Hornady 170 and 165 FTX. Some calculations with the old Powley Computer suggested IMR-3031 as the ideal powder (as I suspected it would) but recommended a load that seemed excessive. There is a digital rendering of the Powley found at kwk.us, and using the same data, it suggested a load of IMR-3031 that was six grains lighter! Accordingly, I started with it (see table).

All of this experimentation was done with the resized 9.3x57 brass, which has a capacity of 61 grains of water, while the refashioned Hayley brass holds 58.5. This makes a difference when using the Powley Computer (either original or digital). The starting loads for the 165- and 170-grain bullets, with either IMR-3031 or IMR-4064, should be fine regardless of the brass, but it wouldn’t hurt to check case capacity anyway.

I never did get to the load recommended by the original Powley slide rule before I ran out of case capacity. It would have been a seriously compressed load. This anomaly with IMR-3031 in the Powley has been noted before, which is why the digital version errs on the prudent side. Anyway, by the time I got above 2,400 fps with the 170-grain bullet, the recoil was becoming a little exuberant for my taste. In a rifle that weighs 6 pounds, 6 ounces, shooting a 170-grain bullet at near 2,500 fps, recoil is noticeable to say the least.

In order to conserve powder, bullets and primers in these uncertain times, I shot groups only with loads that looked most promising – that is, combining adequate velocity without being excessively punishing. The loads I tested with the 165- and 170-grain bullets, using both IMR-3031 and 4064, were near maximum with compressed powder. However, I included the velocities obtained with lighter and heavier loads for reference.

The bottom line of all this, is that I would get some of Hornady’s 125-grain HAP, 165-grain FTX and 170-grain SP bullets, and combine them with IMR’s Trail Boss 3031 and 4064. Out of that, a handloader should be able to get a good short-range varmint and plinking load as well as a fine deer and black bear combination.

And a final work of caution: Should you happen to have (or find) some suitable 200-grain roundnose bullets, I would consult the digital Powley Computer and start with its moderate and sensible recommendation, and only approach the loads arrived at by the original Powley slide rule with extreme caution.

.jpg)