Cartridge Board

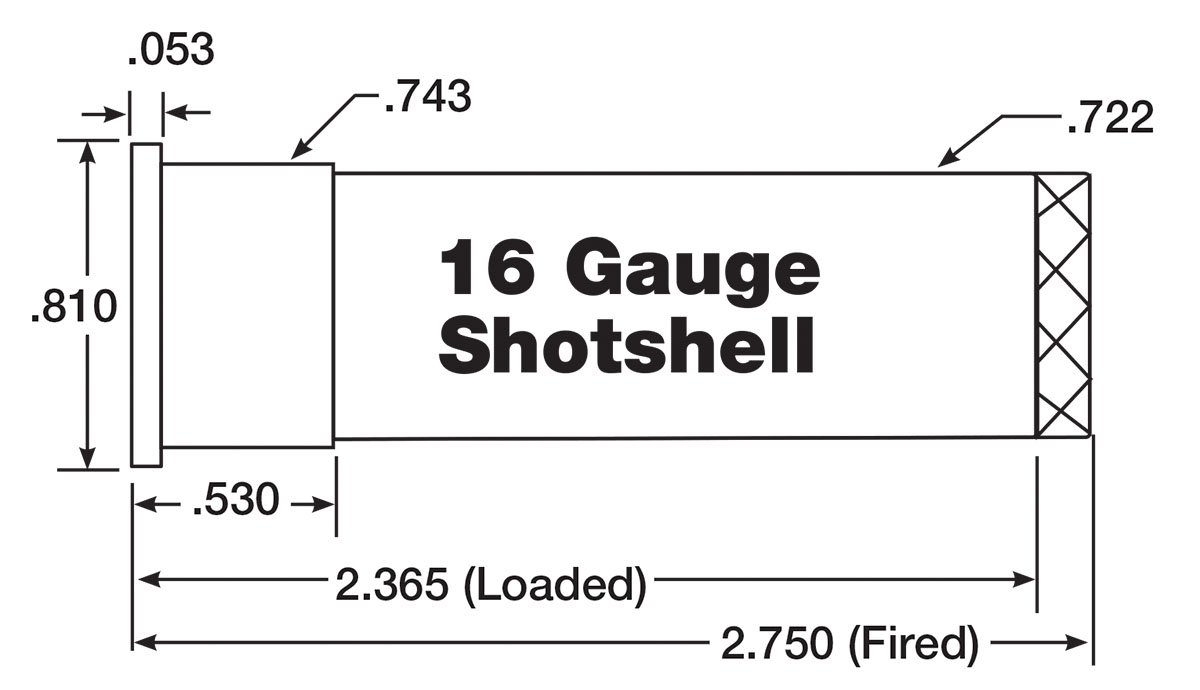

16-Gauge Shotshell

column By: Gil Sengel | February, 25

It seems strange writing the history of a shotgun cartridge. After all, shotguns have been around forever. The Spanish Arquebusier of the sixteenth century fired small square “shot” cut from sheet lead in his matchlock. Millions of folks did the same thing in the following years because, until the last half of the twentieth century, most people on the planet went to bed hungry. A dead deer to chew on was great, but small game and sitting birds were far easier to find. A large bore musket firing small bits of lead (or small stones) made obtaining a source of protein more certain.

Shotgun bore sizes are well known to be determined by how many bore-diameter lead balls weigh one pound. These were 10, 12, 16 and so forth. The diameter of these lead balls was easily calculated to a thousandth of an inch when the general population was still measuring with wooden rulers. In the U.S., these bore sizes were called gauges, probably after the phrase “made to gauge.” The meaning was that new parts were compared to patterns called gauges and rejected if larger or smaller. It made mass production possible.

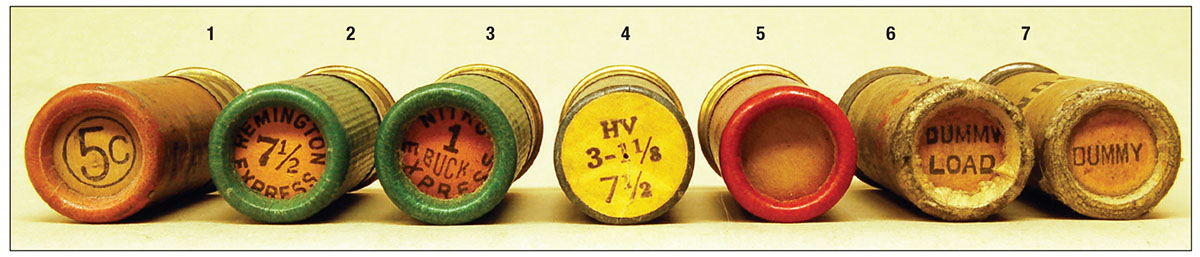

Combinations were unlimited! The large companies provided empty cases and left small outfits to spring up and make sense of the load problems.

Empty cases were available in 10, 12, 14 and 16 gauge by 1875. Atlantic Ammunition Co. of New York produced the first automatic machine loaded shotshells in 1883. Its 1886 catalog shows four 16-gauge loads containing 7⁄8 and one ounce of shot. Eley Bros., London, was selling 16-gauge shells in 1892.

All producers of loaded shotshells sold the 16-gauge. Winchester is a good example. Factory loads were first listed in 1894, though some references say a few years earlier. Gauges were 10, 12, 14, 16 and 20 in paper cases. Three black powder loads were available in the 16-gauge: 2 1⁄2 drams powder and 7⁄8 ounce of shot, 2 3⁄4 drams powder and 1 ounce of shot and 3 drams powder and 1 ounce of shot. Shot sizes were No. 4 to No. 10. The same catalog listed the first smokeless shells, but only one 16-gauge. Apparently, this was “bulk” smokeless because the load was listed as "2 1⁄2 drams powder and 1 ounce of shot.” The cost was just under twice that of black powder cartridges.

From the very beginning, the 16 had a problem: the 14 gauge. References generally don’t mention this gauge. However, given that drawn brass 11-, 14- and 15-gauge empty cases were available for a few years leads me to believe they were used in various percussion-to-breech loading conversions. Think Allin conversion of the U.S. Model 1865 percussion rifle-musket. The fact that the 14 gauge made it into paper-cased shells indicates the existence of newly made guns, which would have hurt 16-gauge sales.

The popularity of the 16 gauge had been increasing ever since smokeless loads became available in the early 1890s. By 1925 powder maker DuPont had developed a dense smokeless called DuPont Oval. It was dense enough that extra case volume was used to add 1⁄8 ounce of shot. The 16 gauge was no longer considered to be a kid’s gun like the 20 gauge but instead almost equal to the 12 gauge.

The original fired length of the 20 gauge was 2 1⁄2 inches; the 16 gauge was the same, but it quickly changed to 2 9⁄16 inches. Both eventually became 2 3⁄4 inches to allow more length for the modern fold crimp. In 1907, however, a group of wealthy duck hunters convinced Winchester to load special 3-inch, 20-gauge cases containing 7⁄8 ounce of shot at 1,300 feet per second (fps). At least Parker Bros. and A.H. Fox made heavy (8-pound) guns to fire them. A history of the 20-gauge, 3-inch magnum appears in this column in Handloader No. 307 and 308. Ego must have played a large part in this, and the ability to brag about having something no one else had.

This silly round bounced along until World War II, when it should have disappeared but didn’t. By about 1960, some 20-gauge guns had 3-inch chambers. Soon all 20s had them. The beautiful 5 1⁄2-pound, 20-gauge bird gun was a thing of the past because of recoil, even though almost no one actually shot the long shells.

How did this affect the 16 gauge? Marketing for the 3-inch, 20 gauge was so intense that 16s became almost impossible to sell by 1970. “Shoot ducks in the morning and quail in the afternoon just by changing shells,” the ads read. Apparently, they worked because I learned demand for 16-gauge ammunition fell off sharply, even though a 1 1⁄4 ounce “magnum” 16-gauge load had been available for a few years but was not popular. Recoil? One industry rep told me dropping 16-gauge ammo had been seriously considered.

Of course, next came the COVID foolishness, lockdowns and ammunition shortages. Just before the ammunition went away, Remington listed three, 16-gauge loadings: one with steel shot, one pushing 1 1⁄8 ounce of lead Nos. 4, 6 and 7 1⁄2 at 1,295 fps and another containing one ounce of Nos. 6, 7 1⁄2 and 8 at 1,200 fps. Winchester showed the same. Likewise for Federal, with the addition of a rifled slug, No. 1 buckshot, 1 1⁄8 ounce copper plated Nos. 4, 5 and 6 at 1,425 fps and 1 1⁄4 ounce copper plated Nos. 4 and 6 at 1,260 fps. The recoil of the last two would be vicious in a light 16 gauge.

The foregoing comes from the last printed ammunition catalogs. When asked about website listings today showing individual 16-gauge loads, I was told by one factory rep, “Oh, those haven’t been made for a couple years.” So much for websites.

Today the proper factory loads for light 16-gauge guns are coming from small companies using new primed Fiocchi and Cheddite hulls stuffed with imported one-piece wads. All these components are available to handloaders. As long as MEC 600 Jr. loaders are available in 16 gauge, the perfect bird gun load pushing one ounce of shot at 1,250 fps will be available forever!

.jpg)