Loading the (Delightful) 28 Gauge

3/4-Ounce Magic

feature By: Terry Wieland | February, 25

Since the 28 gauge is well down the shotshell pecking order (below even the .410 but edging the 16) when shortages occur it will be among the last anyone rushes to produce. Shortages of low-demand shotshells like the 28 will be deeper and longer than high-demand 12-gauge trap loads or 3-inch 20s.

The 28 gauge has had a mixed history since its development in England in the 1800s, but for the past 30 years, the word “renaissance” has been applied more than any other. The 28 is enjoying a period of popularity never seen before; the darling of a class of hunters who proclaim it more “sporting,” as opposed to savages who insist on shooting a “meat gun” like the 12 gauge.

For about 50 years of its life – 1925 to 1975 – it was kept alive and largely confined to its own class of Skeet. Since then, it’s gradually gained fans as a hunting load, especially for quail and doves.

Two serious adherents of the 28 were Gene Hill, who wrote for Field & Stream, and Michael McIntosh, a side-by-side afiçionado who wrote for every major shotgun publication until his death in 2010 and whose work has been compiled in several books. Michael was more technically oriented than Hill, as interested in the ‘how’ and ‘why’ as the ‘where’ and ‘who.’ During his lifetime, he shot every type of gun, in every gauge and configuration, at both feathered game and clay pigeons. His opinions, far more than most, are worth regarding.

Michael McIntosh concluded that the 28-gauge load is so well balanced that it gives near-perfect patterns, is evenly distributed, and has a remarkably short shot string. It doesn’t fling as many pellets, but it flings them all into the right place at the right time.

The key is that 3⁄4 ounce of shot in a .550-inch bore is an almost perfect “square” load, only slightly taller than it is wide.

Since his death, gunmakers and ammunition companies have tried a three-inch magnum 28 with shot charges up to a full ounce. It has not become the standard chambering – yet – but I expect Michael would have reacted much as he did the three-inch 20 gauge, which he called “the worst ballistic abomination ever foisted on the shooting public.”

Heavy charges in the 28 gauge have been around for a long time; way back when, there was even a three-incher, but it never caught on. Nor did a one-ounce load in the standard 23⁄4-inch cartridge Federal tried some years ago. Whether the newer longer 28 gauge will meet the same fate, who knows?

Analyzing all of the above, Michael concluded it was nigh impossible to improve on a 3⁄4-ounce load in any meaningful way. As for velocity, it was proven more than a century ago that velocity in the range of 1,100 to 1,200 fps gives the best patterns. Since trying to increase velocity beyond 1,200 fps accomplishes nothing good, why do it?

Since the 28 gauge’s optimum range is generally acknowledged as 35 yards, a No. 8 lead pellet retains sufficient energy at that distance to handle pretty much any bird except for, perhaps, a big fleeing cock pheasant. This assumes an appropriately tight choke that concentrates enough pellets for the necessary multiple hits.

Speaking of the gun itself, the British “rule of 96” states that a 28-gauge gun can be as light as 4.5 pounds. But just because it can be, doesn’t mean it should be. To me, the ideal weight for a game gun of any gauge, including the 12 gauge, is six to six and a half pounds. A six-pound 28 gauge can have 30-inch barrels, which make it handle and swing like a dream; shooting standard loads, its recoil is so light it hardly qualifies as negligible.

At various times, I’ve shot ultra-light 28s with barrels as short as 26 inches but was never able to hit anything. This flies in the face of conventional wisdom, which glorifies wand-like 28s, but I offer it for what it’s worth. I asked Tony Galazan, proprietor of Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing Co., who knows more about building shotguns than anyone else in the country, and is an excellent shot to boot, what he considered the ideal barrel length for a 28 gauge. With no hesitation, “Thirty inches.”

Finally, choke. Modified (M) is a neglected constriction, but it shouldn’t be. Either Modified or Improved Modified (IM) in a 28 gauge will give you a nice snug pattern, and not just at one distance. It will be effective, essentially, from 20 yards out to 35 or, stretching it a bit, 40.

Now picture something. Let’s say you have a 12 gauge with a 1 1⁄4 ounce load, and on the patterning board, you see that about 60 percent of its pellets are in a good, dense killing circle. Sixty percent is 3⁄4 ounce.

Handloading the 28 gauge is not rocket science, but there are some things to keep in mind. First, pressure. The 28 gauge operates at considerably higher pressure than a standard 12 gauge – 11,000 psi versus 9,000 psi, although there is a broad range from light loads to heavy. This requires a slower burning powder, which means there are fewer suitable powders available.

Even minor changes in components can have adverse effects on pressure. For example, Ballistic Products tested exactly the same load, switching only the primers, and found a disparity of 3,000 psi between the lightest and heaviest. Similarly, a load with one formula, increasing only the powder charge, gave a velocity range from 1,150 to 1,300 fps and a pressure range from 8,200 to 12,000 psi.

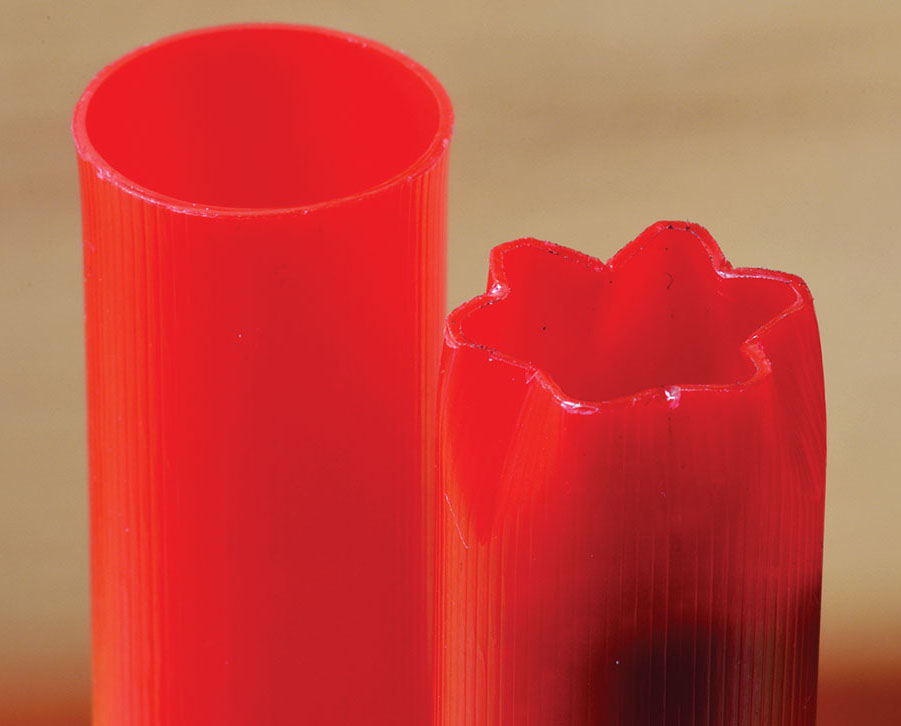

Because of its relatively low demand, you are not going to find the range of components nor, obviously, as many loading options. Shotshell load data dictates hull, primer, powder, wad and shot charge plus, occasionally, the addition of a card wad to take up space or a buffer to protect the pellets. Since all of these have to pack into the hull snugly, like a well-packed sausage, in order to function properly, you cannot substitute components willy-nilly.

Other powders recommended for 3⁄4-ounce, 28-gauge loads include Longshot (out of stock) and Alliant 20/28 (unobtainable everywhere I looked). Hodgdon has formulae for IMR Blue, 800-X, PB, SR-4756 and SR7-625, all of which are discontinued. You see the problem.

In fact, when I first scanned the load charts in Ballistic Products’ Small Bore Manual, out of more than 50 formulae, I could find all the components for exactly one of them! Others were out of stock or discontinued.

You may insist it’s more economical to buy new ammunition and then reload the hulls, but I thought it better to bite the bullet and buy 500 Fiocchi primed hulls, 3,000 Fiocchi primers and the ubiquitous Ballistic Products SG28 wad, which can be used in almost anything. With my ten pounds of W-572, I’m set well into next year.

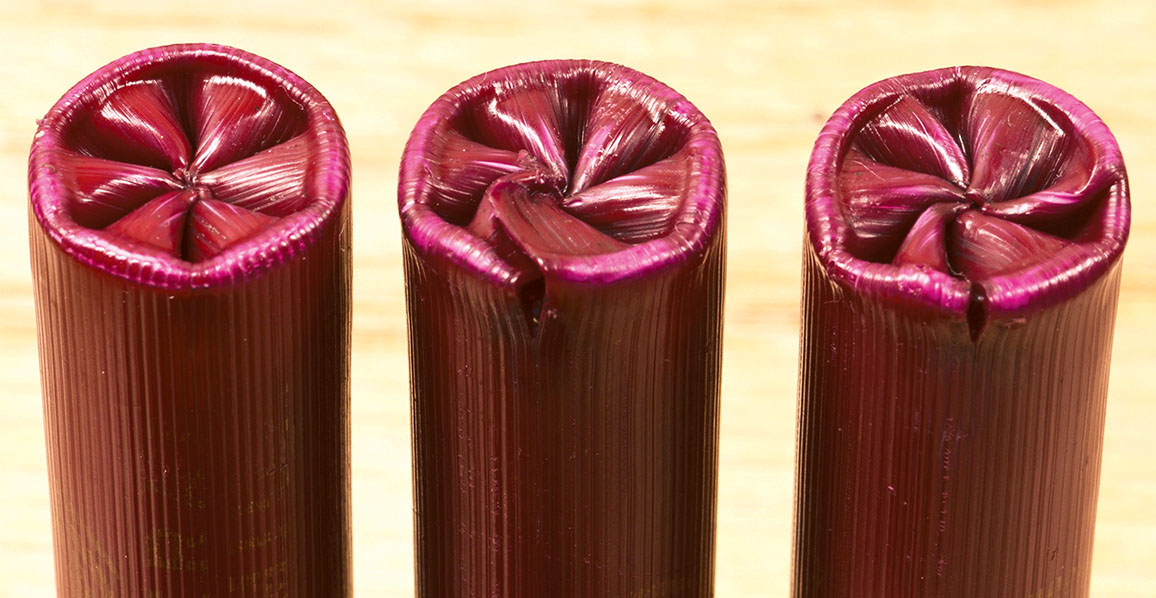

Both Hodgdon and Ballistic Products provide a variety of loads using those components, with varying amounts of powder affording a suitable range of velocities. Truth to tell, I got better crimps using Universal because it fills the case a little bit better, but you make do. Since I was loading a very light charge, I felt safe in putting a thin over-shot wad in the case to take up the extra space and provide a solid surface to support the crimp. The wads weigh only 2.1 grains (same as two No. 8 pellets), which is less than the variation from one shot charge to the next. An alternative is a thicker .410 wad placed in the bottom of the shot cup. This adds 3.5 grains, equivalent to three No. 8 pellets.

I know I have warned against substitution and deviating from published formulae, and I do NOT recommend it, but I think these two measures fall well within safe limits since 3⁄4 ounce of No. 8s can vary by half a dozen pellets and the charge bar in my MEC throws five grains less than a full 3⁄4 ounce (328 grains) anyway.

The bottom line? With shotshells, it’s always best to figure out a good standard load and then lay in a stockpile of everything related to it. Much experimenting with shotshell loads leads to a lot of wastage, with partial bags of this and a few hundred of that and not enough of anything to do anything meaningful.

In this way, I guess the 28 is the ideal gauge: Simply settle on a good 3⁄4-ounce load, lay in the wherewithal and forget about it.