I’ll Have a 30 GIbbs!

Nipping at the Heels of the 300 H&H

feature By: Wayne van Zwoll | February, 25

Until I read that in Francis Sell’s fine 1964 treatise on deer hunting, I’d not heard of a 30 Gibbs, and it would be some years before I saw a rifle so chambered.

But I didn’t need another 30-06.

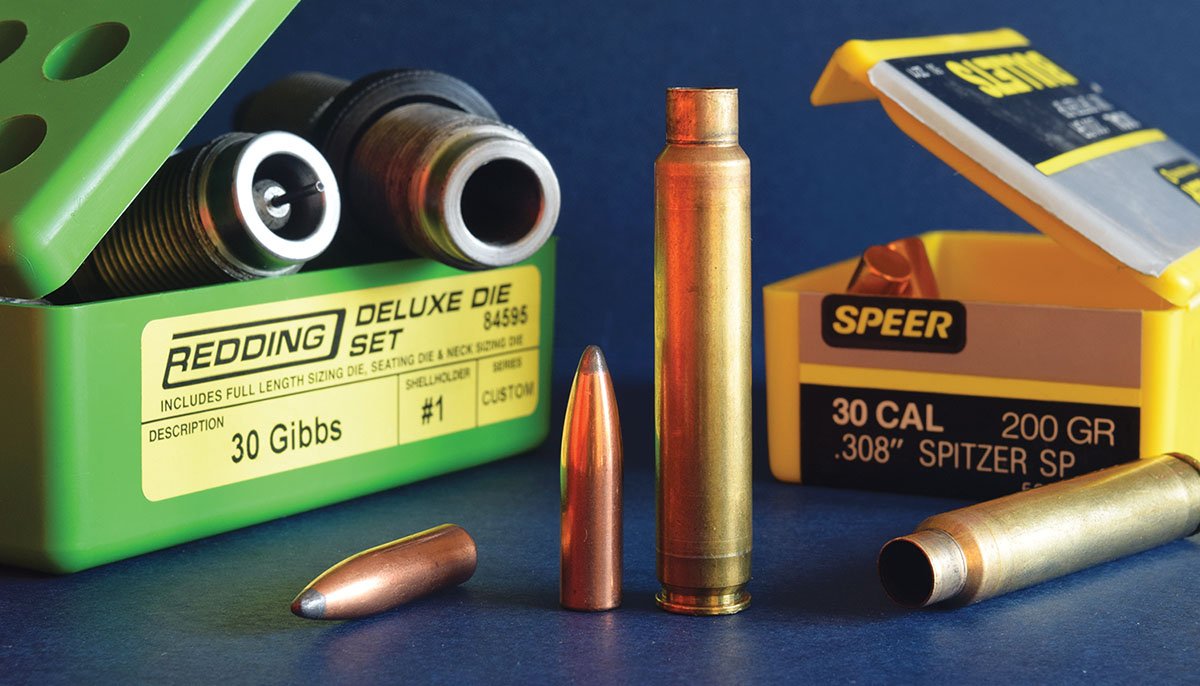

About to tuck it back, I glanced by habit where re-chambering begs a barrel mark. There it was: 30 Gibbs. The proprietor had no cartridges or dies and little to say about this wildcat. “First I’ve seen.”

Had the price been unreasonable, I’d have paid it anyway.

I read about Rocky Gibbs and his cartridges. The 30-06 was the parent case for most. To boost its case capacity, he moved the shoulder forward.

Bob Hagel, who wrote with authority borne of long experience, was not impressed with the result. In Handloader (No. 73, May-June, 1978), he wrote: “For the record, I found that when using cases of the same weight, both fired and full-length resized … there is only 5.8 grains difference in water capacity with the 180-grain Hornady flat-base bullet seated to the same depth.”

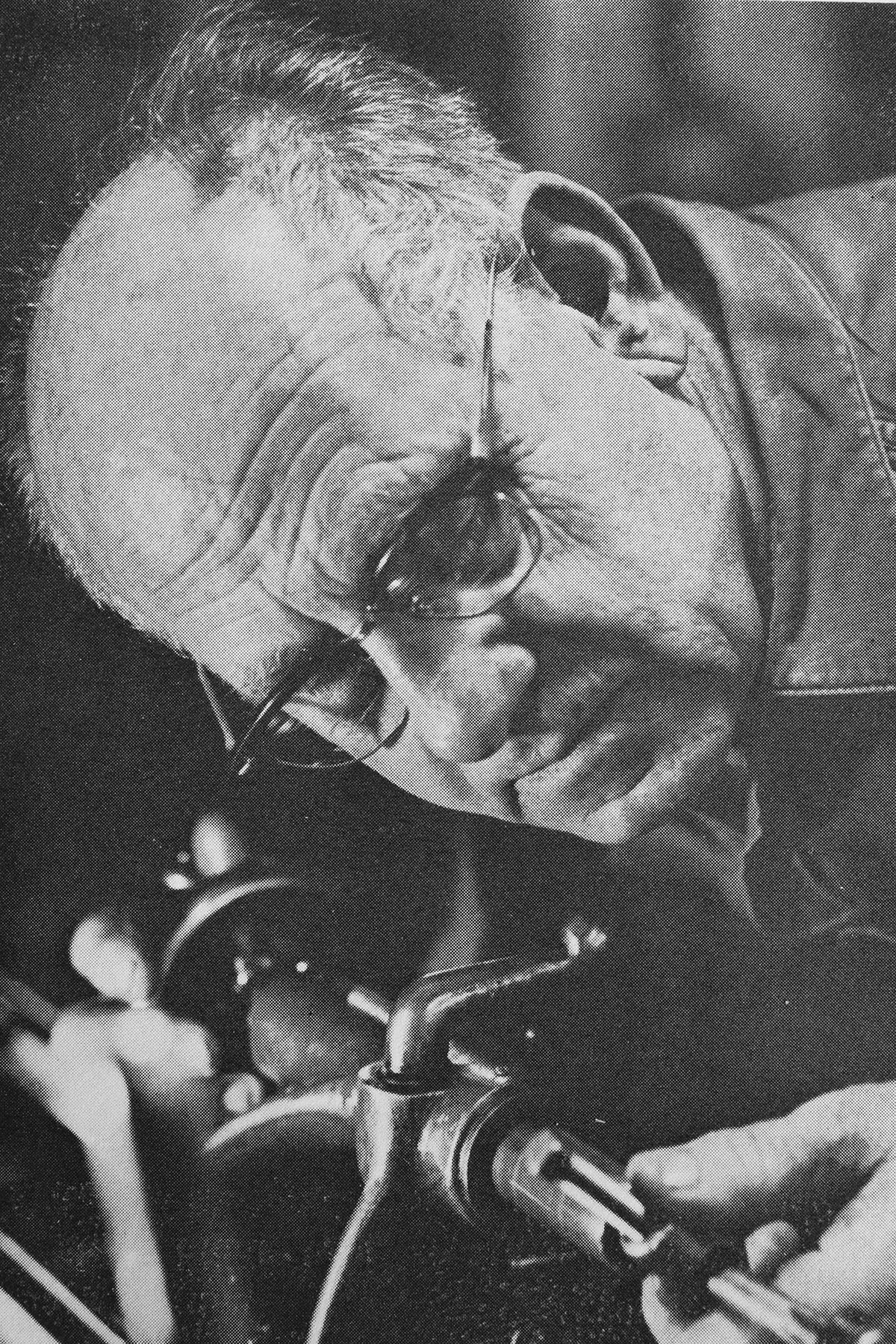

Manolis Aamoen Gibbs was born on November 12, 1915. Childhood typhoid cost him the sight in his right eye. So he learned to fire rifles from his left shoulder. After graduating high school in Gainesville, Texas, he took a train to California, the land of promise for refugees savaged by the Dust Bowl. As the rails carried him to Richmond, he marveled at the great white-capped pyramids hazy on the horizon. “Those are the Rocky Mountains,” a passenger told him. The name had a strong, enduring ring. It so appealed to Gibbs that he adopted it and changed his middle name, too.

Rocky trumpeted velocities that left seasoned riflemen scratching their noggins. His claim that 63 grains of IMR-4350 in his .270 sent 130-grain bullets at 3,430 fps put it in league with the 270 Weatherby Magnum – quite a stretch, given the greater case capacity of the Weatherby and the fact Roy Weatherby was hardly bashful puffing his hotrods! But Rocky didn’t back down, declaring his 270 Gibbs “the best all-around cartridge for a handloader.”

Rocky Gibbs tested novel handloading methods. His published booklet, Front Ignition Loading Technique, described duplex loads pioneered by Charlie O’Neil, Elmer Keith and Don Hopkins of OKH fame. Rocky cautioned handloaders to work up loads prudently and to heed signs of high pressure, which “may be as subtle as a cratered primer.” He declared snug primer pockets a sign of safe handloads. Sadly, just three years after his move to Idaho, a house fire consumed his records and his stock of booklets.

Using 30-06 cases, you can expand necks in a 338-06 sizing die, then run them through a 30 Gibbs die. The .338-06 neck is adequate for headspacing, and you won’t mangle cases or take as many neck-sizing steps as you might starting with 35 Whelen brass. Either way, starting with new, not once-fired cases makes sense. Cases emerge with two shoulders. Firing in a 30 Gibbs rifle erases the lower, original shoulder. You’ve moved the datum line forward safely. I’ve had no problems using full-power loads for case forming, though accuracy is typically best with fully formed brass, especially when the new neck isn’t concentric with the rest of the case or the bore. This happens often and is something the handloader should be aware of. Neck turning is a prudent step toward concentricity.

Gibbs cartridges put near-magnum bullet velocities in reach of anyone with an 03A3 Springfield. These were peddled by surplus houses in the ’50s and ’60s for $29.95. (Weep with me.) Rebarreled, they could accommodate any of the wildcats from Gibbs Rifle Products.

The 240 Gibbs, from re-shaped 25-06 brass, isn’t as useful as it is fast. Rocky claimed 3,600 fps with 75-grain bullets, 3,500 with 85s and 3,250 with 105-grain Speers. The only rimless wildcat that shot flatter, he assured shooters, was the 25 Gibbs. It out-performed the 25-06 (then still a wildcat), almost matching the 257 Weatherby Magnum but with less bolt thrust. Rocky was said to recommend the .25 to customers dithering over their options. Cynics questioned the data: 3,900 fps from 75-grain bullets and nearly 3,550 with 100-grain, but the .25 Gibbs ranked third in sales, behind Rocky’s .270 and .30 Gibbs.

The 1950s weren’t kind to hot 6.5mm cartridges, as Winchester found with its .264 in ’59. Rocky said his 6.5 was “a vicious big game rifle, fit for gophers and grizzlies.” A touch of hyperbole there. Still, range trials by experienced shooters turned up some stellar groups. Bullets of 100 to 140 grains clocked from 3,450 to 3,050 feet per second (fps). The 7mm Gibbs sent 139-grain missiles at 3,300 fps, 154s at over 3,100. Rocky reported 2,950 with Hornady’s 175-grain game bullet, which he liked immensely. The 7mm Gibbs might have fared better in a market bereft of the 7mm Weatherby and Warren Page’s 7mm Mashburn. When, in 1962, Remington pitched big money into ads for its fresh 7mm Magnum in the new, eye-catching Model 700 rifle, all the competition felt its shadow!

Parker “P.O.” Ackley once observed the most efficient .30-bore cartridge would hold about 65 grains of IMR-4350 to the base of the neck. Depending on the source, a standard 30-06 case holds about 60, given light taps to settle the powder, 30-06 Ackley Improved cases (Winchester-Western) hold an average of 62. Those fired in my 30 Gibbs hold 65. So Rocky bumped capacity by 5 percent over the 30-06 A. I., whose 40-degree shoulder gives it a 3 percent edge on the unaltered ’06 case. Yes, that .250 neck is short – but not much shorter than the .264 neck of the 300 Winchester Magnum – and the 300 Savage, popular since its 1920 debut, has a .220 neck!

In 1958 Rocky added the 338 Gibbs to his line. Unlike his .30 and 8mm, it required a new barrel or a reboring job, as well as a fresh chamber. High-speed .33s of that day were wildcats. The .33 Winchester had died with the 1886 lever rifle in 1936 and, at its friskiest, could kick 200-grain flat-nose bullet at only 2,400 fps. Fred Zeglin, in his excellent book on wildcat cartridges, wrote that Rocky favored 250-grain bullets for his .338. But such projectiles ate a lot of powder space. To reach 2,750 fps, a pointed bullet of that weight and diameter needed more space than available in any re-shaped 30-06 hull. Speculation as to how the .338 might have sold absent the debut that year of Winchester’s .338 Magnum is pointless. The superb Model 70 Alaskan made rifles in 8mm Gibbs all but irrelevant.

Published velocities of Gibbs cartridges are often dismissed as untenable within accepted pressure limits. While I generally avoid feeding my rifles maximum loads, I’m loath to declare what can’t be done. Initially, Winchester’s .264 Magnum was listed as hurling 140-grain bullets at 3,200 fps. That figure was later reduced to 3,030. Anyone clocking 140-grain softpoints from the .270’s much smaller case at 3,100 had to question this shift! I’ve stoked 140-grain loads in the 26-inch barrel of my Model 70 .264 to well over 3,200, so I won’t say Rocky didn’t get the velocities he claimed.

On the other hand, he had a vested interest in high numbers. He could get them by listing only the top-most of the velocities chronographed. Barrel length also mattered. Rocky, it’s been said, measured his barrels from the front of the chamber to the muzzle, not from breech to muzzle.

Fashioning brass for my 30 Gibbs, I sized 30-06 cases in 338-06 dies, then in 30 Gibbs dies to give them a headspacing stop. Mild 50-grain charges of IMR-4350 behind 165-grain bullets fire formed a new shoulder and erased the old. These loads averaged 2 minute of angle (MOA) at the range. Fully formed cases snugged groups. Using data for the 30-06 as a baseline to work up 30 Gibbs charges, I first added a percentage of the maximum for the 30-06. This boost did little for light-bullet loads. Ackley had published 3,450 fps for 150-grain bullets. My first loads fell well shy of that, not even matching his 3,150 fps for 150s from the 30-06 Improved! The Gibbs’s additional case capacity trumped my increased powder charges.

Judging from the condition of spent primers (a few extruded, none flattened) and case heads (no worrying ejector marks), also the ready extraction of all empties, I’ve plenty of room to increase charges. While a few loads brought coarse stick powders to the base of the neck, none were compressed. I seated the bullets well out because, well, I could. The rifle’s throat was generous. So, too, the magazine.

This 03A3 seemed happy drilling 11⁄4- to 11⁄2-MOA groups. So am I. That level of accuracy is more than sufficient for hunting. In a nod to the handload that took my first elk – 180-grain Speers in a 300 H&H – I chose these bullets, with a charge of IMR-4451 for my elk hunt with the 30 Gibbs.

I’ve shot elk with the 30-30 Winchester, 303 Savage, 32 Special and .250/3000 Savage. At woods ranges, those and a battalion of more capable cartridges would have toppled that six-point. Thumbing .30 Gibbs loads into the magazine, I was no better equipped to shoot elk than if the rifle had remained a 30-06, but my 03A3 and its hand-fashioned cartridges brought to mind another era – people and events that bear remembrance. Or imagining.

This Springfield is my connection to a colorful wildcatter and a time that wears well in memory. Rocky Gibbs challenged shooters to hurl bullets faster, on flatter arcs, from tired infantry rifles and range-pails of 30-06 hulls. He died of leukemia in 1973. He was 58.

.jpg)

.jpg)