From the Bench

A Tale of Two Kabooms

column By: Art Merrill | February, 25

These handgun catastrophic failures occurred one after the other to the same man during the same range session, just minutes apart. The gentleman who handloaded the cartridges for both revolvers is a longtime handloader and Cowboy Action shooter, and quite knowledgeable about period revolvers and quality reproductions like these.

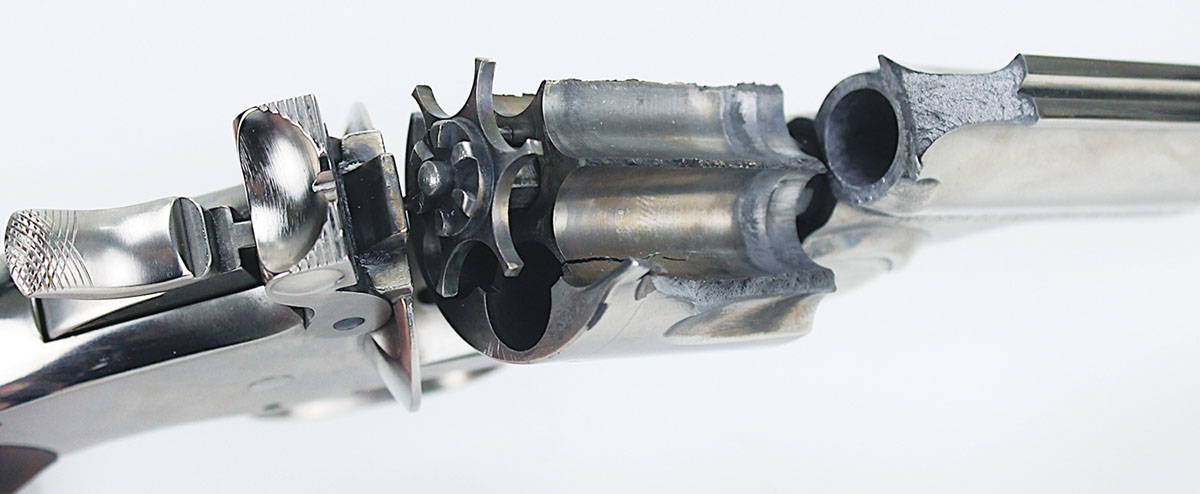

The first revolver is a Model 1872, replicating a Colt 1860 Army percussion conversion to 44 Special. What was assumably an unintentional double charge of Bullseye powder ruptured not only the brass case but also split open the outer wall of the steel cylinder. The blast rocketed upward as the thin wall of the chamber split and peeled forward nearly the entire length of the cylinder. Neither the shooter nor anyone else was injured. The only damage was to the revolver’s cylinder, which was replaced. The mangled cylinder now serves as a pen and tool caddy – and as a reminder for caution – on my reloading bench.

The gentleman is 84 years old and acknowledged he is suffering from the beginnings of dementia. “I’m done handloading,” he said when he brought in the revolvers in hopes of repair. I examined one of his 45 Colt handloads accompanying the revolvers and weighed the charge of Bullseye: 16 grains under a 230-grain lead bullet, double a maximum load by anyone’s data. I also noted he had inadvertently loaded the cartridge into a case with an already-expended primer – which, in the end, is just as well. I don’t know the overload he fired in the Model 1872, but if it was the same powder charge as in the 45 Colt demolition, it would have been a triple overload for the 44 Special.

The gentleman is unable to explain how he came to so grossly overcharge at least four cases among two disparate cartridges. Now, of course, all of his remaining handloaded cartridges are suspect and unusable.

We also must maintain alertness and focus at the range and in competition. Once, as a rangemaster walking the firing line, I happened to pass behind a shooter when I heard him fire the telltale “pop” of a squib load. He looked at his pistol, flipped it over to look at the other side, then raised it to fire again when I stopped him. “Yeah, it didn’t sound right,” he said, but he had never experienced a squib load and so would have continued shooting. I had him field strip his pistol, and I drove the stuck bullet from the bore with a cleaning rod, and he went back to shooting with an easy lesson learned.

There’s more to handloading and shooting than alertness and focus. It is sad to say that there are some folks who just don’t have the mental acuity for either pursuit, and they can unintentionally pose a hazard to others. That necessary acuity is exemplified in arming oneself with knowledge, completely understanding the information (written, verbal, visual, audible and tactile) and its ramifications and following safe practices that are practices because they were learned – and, unfortunately, continue to be re-learned – the hard way.

The two-kaboom incident documented here illustrates for us that if something “doesn’t feel right” when shooting, then something probably isn’t. That mental acuity, as well as non-distracted, focused attention, is an absolute requirement for those who pursue handloading. Handloaders of any age who fail in these responsibilities risk not only themselves but bystanders, as well. No, it won’t be a joyous decision when we finally make it, but may we all recognize when it’s time to hang up our spurs.