.270 Winchester

Testing New Bullets and Powders

feature By: John Barsness | October, 19

When the .270 Winchester appeared in 1925 as one of the rounds in the company’s new Model 54 bolt-action rifle, the chambering apparently did not sell spectacularly. This was partly due to established cartridges such as the .30 WCF (.30-30), then three decades old, and the .30 Gov’t ’06 (as the Model 54 was stamped). Many hunters assumed the .270’s original factory

load, a 130-grain bullet advertised at 3,160 fps, was too fast and light for big game because they had grown up shooting the .44-40 and .45-70 and had just gotten used to .30-caliber bullets for big game.

Even half a century later many older hunters distrusted the “new” cartridge. I purchased my first .270 in 1974, whereupon my grand-father-in-law said, “I tried one of those, kid, but most stores did not carry ammunition.” Like many Western hunters of his generation, Ben was a confirmed .30-06 man, whose lone big-game rifle was a Winchester Model 70 .30 Gov’t ’06, which he traded his .270 for in 1937. Other “young” hunters also encountered .270 resistance: Friend Kirk Stovall, a year behind

me at Bozeman Senior High School, was afraid to buy a .270 Winchester until well into adulthood, because his father (another .30-06 man) hated the cartridge.

Despite such skeptics, the .270 eventually became one of the two most popular non-military big-game cartridges introduced before World War II, the other the .30-30.

Despite the appearance of many other rifle cartridges since 1925, the .270 still ranks way up there. This popularity is often attributed to a writer named John Woolf O’Connor, born in Arizona in 1902. Nicknamed Jack, he eventually became the shooting columnist for Outdoor Life, back when “outdoor life” primarily meant hunting and fishing, not mountain biking.

O’Connor used the .270 a lot, partly because of living in the American West. Shots at big game tended to be longer than “back east,” where the .30-30 was the quintessential deer cartridge. The flat trajectory of the .270 made 300- and 400- yard shots possible with iron sights, which dominated hunting until after the war, and the 130-grain bullet worked great on deer and wild sheep.

The .270 really became popular after WWII, partly because Outdoor Life was among the magazines distributed to American soldiers, though several other factors converged. More Americans moved West, scopes became more reliable and affordable and more rifles came from factories ready for scope mounts.

Plus, in 1948 John Nosler started selling his Partition bullet to handloaders. The big problem with early high-velocity big-game cartridges had always been sufficient penetration, but the Partition solved the problem. I started handloading Partitions in the .270 in 1977, when they were still turned on a lathe and had an exterior “relief-groove” around the Partition. Since then my personal .270 experience has included plenty in North America on big game up through elk and moose, and in Africa on elk-sized plains game. It has performed consistently well, which is why modern claims that the .270 is only adequate for “deer-sized” game are puzzling.

However, I doubt the original 130-grain factory load attained its advertised velocity, especially in the Model 54’s 24-inch barrel, though it probably did get around 3,000 fps. The .270 appeared a year before the U.S. Government requested that American firearms ammunition companies get together and agree on consistent chambers, ammunition and pressures. The result was the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers Institute, (SAAMI).

Before SAAMI, such standards did not exist. Maybe original Winchester .270 ammunition did get 3,160 fps in long test barrels, but the powders of the day were relatively fast-burning. IMR-4350 did not appear until 1940. At the time it was by far the slowest-burning powder then available to handloaders, which made Roy Weatherby’s magnums possible. (In fact, it was so revolutionary that in later years O’Connor referred to it as the “Wonder Powder.”) Yet in the last decade, no pressure-tested data lists .270 loads with IMR-4350 and 130-grain bullets at more than about 3,100 fps from SAAMI-standard 24-inch test barrels.

After the war, Bruce Hodgdon started selling a military-surplus cannon powder he originally called “4350 data” powder, since IMR-4350 loading data could be used, but the powder turned out to be noticeably slower-burning and eventually was rebranded as H-4831.

O’Connor started loading H-4831 in his .270s about the time he moved his family from Tucson to Lewiston, Idaho. Ray Speer found a house for them on a hill a short walk behind the Speer factory and gave Jack a key to access the factory’s indoor test range during off-hours. O’Connor reported very high velocities and fine accuracy with H-4831, and it soon became the .270 powder.

Many loading manuals of the day listed very high .270 velocities, not only for H-4831 but other powders. A major loading manual published in the early 1970s lists four powders getting 3,200 fps from a 24-inch barrel: IMR-4350, H-4831, Hodgdon 205 and (!) IMR-4320. Today Hodgdon owns the IMR brand and lists a top 130-grain velocity of 2,916 fps with IMR-4320 from a 24-inch barrel.

This occurred because many companies developed their loading data like optimistic handloaders do today – by adding powder until rifle or brass show signs of distress, then using the heaviest charge that “appears safe.” Speer, in fact, used the method for decades despite having copper-crusher test equipment, apparently because nobody at the company knew how to use it correctly. By the 1980s, more ammunition companies started following SAAMI pressure and velocity guidelines, and electronic testing resulted in more consistent data – and lower velocities.

H-4831 also changed over the years because the original military-surplus powder was pretty much used up by the mid-1970s. Hodgdon replaced it with a similar powder it also called H-4831, made in Scotland, and later replaced that powder with H-4831 made in Australia.

Today’s Aussie H-4831 is the Extreme version and comes in two variations, one similar in appearance to the mil-surp powder and a “short-cut” version with granules about two-thirds as long, which flow more consistently through powder measures. Hodgdon says both versions have the same burn rate, and my present batches of both chronograph within a few fps of each other.

They are not as “hot” as the original powder. In 2015 I still had an unopened pound of military H-4831 and compared it with Extreme H-4831 by loading the same 130-grain Hornady Spire Point bullet with the same 61.0-grain charge. The old H-4831 got almost 100 fps more velocity. (These and other results were reported in “Different Batches, ‘Same’ Powder” in Handloader No. 298 (October-November 2015) – and if somebody out there worries that 61.0 grains is excessive, Hornady’s latest manual lists a maximum charge of 62.0 grains with 130-grain bullets.)

However, velocities with the original powder varied considerably in different temperatures. In another test, the old H-4831 with 130-grain bullets lost 150 fps when chronographed at 70 and zero degrees Fahrenheit. Loads with Extreme powders normally vary no more than 25 fps at those same temperatures.

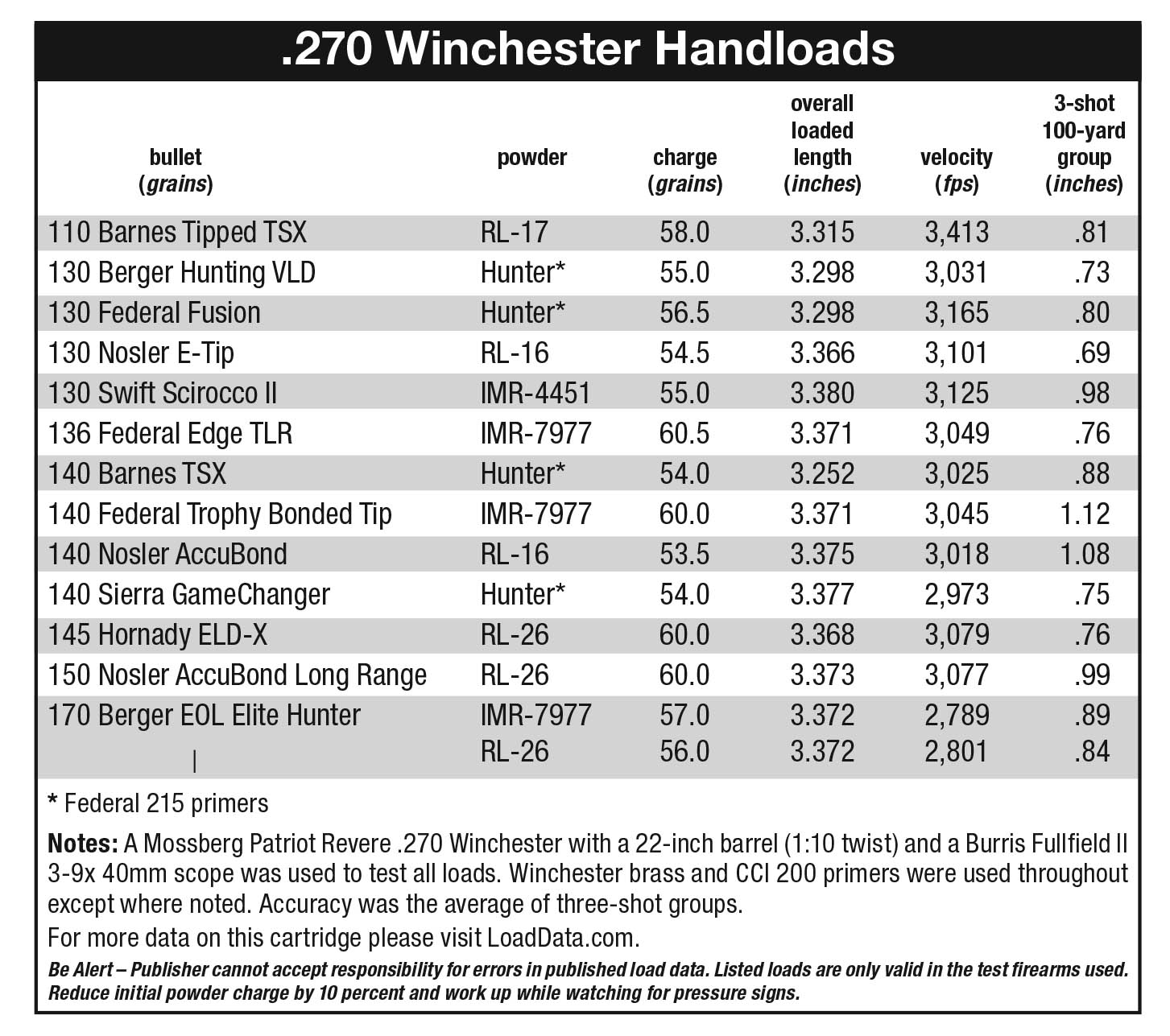

Many new .270 bullets and suitable powders have recently appeared, and even the Extreme versions of H-4831 are not always the top choice, even though many hunters still do pretty well with H-4831, often with Nosler Partitions. For this report, I decided to define “new” as powders and bullets introduced in the twenty-first century.

Powders were selected by my usual method, searching published data for the highest velocities for various bullet weights. While many handloaders claim to be more interested in accuracy, I have noticed most accuracy addicts also like velocity, partly so they can post photos of their chronograph’s readings on the Internet.

All the powders selected turned out to be double base with an added dash of nitroglycerin, absent from single-based powders, the reason they produce more velocity. Most are also advertised as temperature-resistant. However, in my tests, even the two powders not claimed as temperature resistant, Alliant RL-17 and Ramshot Hunter, proved to be far less cold-sensitive than original H-4831.

Most also included decoppering agents, another modern trend, though some .270-appropriate powders included decoppering agents as long ago as the 1920s. While this not always eliminates copper fouling, it definitely reduces it, as my Gradient Lens borescope again proved during the test shooting. The effectiveness of decoppering agents (usually bismuth) depends both on the powder charge and how much a particular bullet fouls.

One surprise occurred during the powder-data search. Alliant Reloder 26 recently became the new “Wonder Powder” with heavier bullets in the .270, due to safely pushing 150-grain bullets over 3,000 fps, even from 22-inch barrels. However, RL-26 pretty much fills the case with 150s, and I expected the two other new Reloder rifle powders, RL-16 and RL-23, to provide faster velocities with bullets under 150 grains. That proved to be true, but oddly enough, Alliant’s own data shows that faster-burning RL-16 beats RL-23 slightly with 130/140-grain bullets, so got the nod.

The test rifle was a Mossberg Patriot Revere model with a walnut stock and lots of figure. Aside from good accuracy obtained from other recent Mossberg rifles, the Patriot was picked because in previous shooting it produced more velocity than most factory .270 barrels, which normally means the chamber and bore are close to minimum SAAMI dimensions.

With scope, the rifle weighed 8 pounds, 11 ounces, about a pound more than O’Connor preferred. However, one thing I discovered when using heavier bullets with new “Wonder Powders” in other .270s is higher velocities make an O’Connor-style rifle kick more like a 7mm Remington Magnum. The extra weight of the Mossberg, and its thick, soft recoil pad made shooting a bunch of test loads more pleasant, and probably more accurate, especially toward the end.

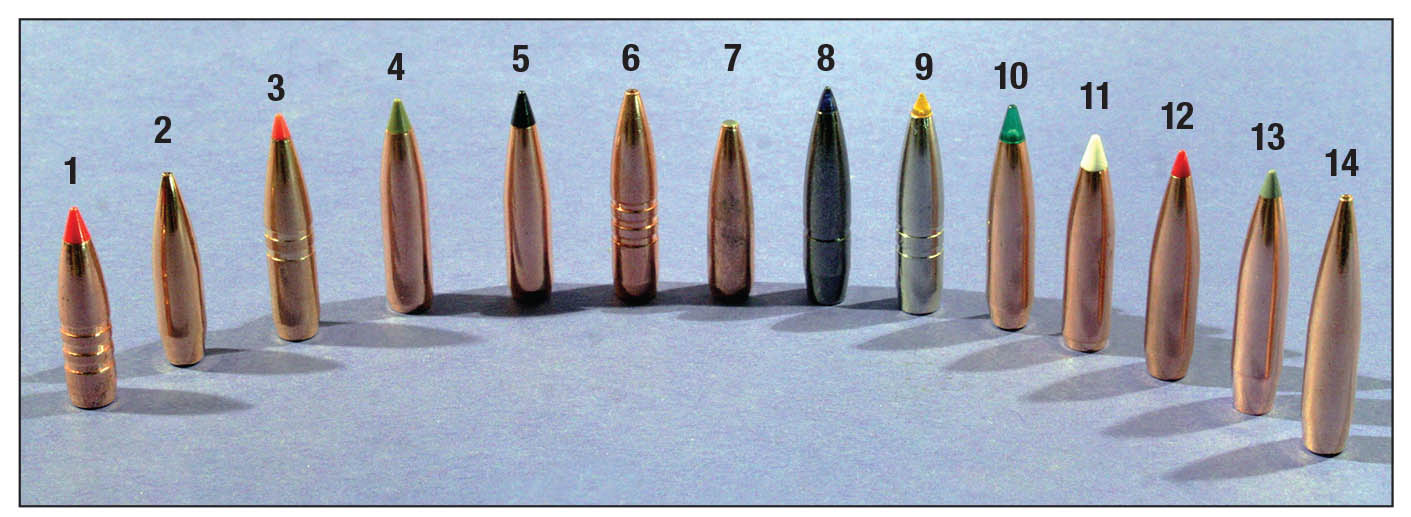

The new bullets included models from plastic-tipped cup-and-cores such as the Hornady ELD-X and Sierra GameChanger to bonded lead-core bullets and monolithics. Several have very high ballistic coefficients (BC), and due to their long ogives could not be seated anywhere near the lands and still fit inside the Patriot’s magazine.

When possible, my standard test procedure for big-game rifles is to start with lead-core bullets seated .03 inch from the lands, and monolithics .05 inch, since they normally shoot more accurately with more “jump.” However, one of the interesting aspects of the recent high (BC) trend is even the lead-core bullets often shoot very well when seated farther from the lands. This proved true during the tests with every high-BC bullet, some seated over .10 inch from the lands. (This is also aided by tighter-diameter throats in many newer factory rifles, apparently including the Patriot.)

Another overall trend was finer accuracy with loads near or at published powder-charge maximums. This commonly happens with modern powders because they burn most consistently at higher pressures. However, I did not try the maximum charge of Hunter with the Berger 130-grain VLD Hunting bullet because field experience indicates Bergers expand most consistently at a maximum of around 3,000 fps. Plus, the bullet shot very well with a slightly sub-maximum load.

The Berger 170-grain Extreme Outer Limits Elite Hunter may take first prize for the longest name of any hunting bullet. It was also the longest bullet tested, the reason Berger recommends a rifling twist of 1:8. The Mossberg’s twist in the standard .270 is 1:10, but I was sure the Berger would stabilize anyway.

First, Bryan Litz’s fine book Ballistic Performance of Rifle Bullets (2014) not only lists tested BCs for hundreds of bullets, but how well they stabilize in different twists. This is not simply a matter of landing either point-forward or sideways, because ballistic coefficient is also affected by how firmly a bullet stabilizes. Even in Litz’s “worst case” conditions (meaning sea level in colder temperatures), the 170 should stabilize in a 1:10 twist, and in the “best case” (higher elevations at warmer temperatures) it stabilizes pretty well, though ballistic coefficient will not be optimal compared to a 1:8 twist.

Berger’s website twist calculator, based on the formula developed by the late Don Miller, indicates the average G7 BC of .343 will still be .320 from a 1:10 twist in typical fall hunting conditions in my part of Montana. If a reader is not familiar with the G7 BC, .320 would be roughly equivalent to a G1 BC (listed by most bullet makers) of about .630. For comparison, a typical 150-grain .270 spitzer has a G1 BC of around .450.

Plus, I had already tried the 170-grain Berger at a local range in another 1:10 .270, where it shot well on an average summer afternoon at a little over 4,000 feet above sea level. However, like many of the other bullets it shot best when loaded warmer.

The charges of IMR-7977 and RL-26 used with the 170-grain Berger were extrapolated from data for the Nosler 160-grain Partition, since neither Hodgdon or Alliant lists data for the Berger. That said, Speer data for its discontinued 170-grain roundnose included muzzle velocities of around 2,800 fps. If anybody out there really wants to approximate the long-range ballistics of one of the smaller, trendy 6.5mm rounds with their “antiquated” 1:10 twist .270 Winchester, the Berger comes very close.

The Hornady 145-grain ELD-X and Nosler 150-grain AccuBond Long Range also have very high BCs and can be started at over 3,000 fps with RL-26. Both are excellent all-around hunting bullets, and thanks to the higher muzzle velocity, out to more than 500 yards shoot flatter and drift less in the wind than the 170-grain Berger at 2,800 fps.

For those hunters who shoot at more conventional ranges, plenty of new bullets provide everything from high-velocity zapping to super-deep penetration on larger game. The really good news involves Federal, now back in the handloading component business after a several-year vacation. Its Trophy Bonded Tip has been available since 2017, but now the company also sells the 136-grain Edge TLR, another bonded bullet with a solid shank but more lead in the nose and a hollow plastic tip for wider

expansion at longer ranges. There’s also the popular 130- grain Fusion featured in factory ammunition, a relatively inexpensive bonded bullet with a medium-weight jacket.

Included in the tests were several monolithic bullets in the 110- to 140-grain range that shoot very flat at conventional ranges, penetrate deeply while ruining relatively little meat and recoil modestly, one of the often overlooked original virtues of the .270 Winchester. Combined with improved powders, all these new bullets make the old cartridge work better than ever.