Cartridge Board

.44 S&W Special: The Beginning

column By: Cartridge Board | October, 19

The .44 S&W Special was the result of at least 60 years of firearm evolution. It does not seem to be known exactly when the .44 caliber became associated with handguns, but its future and enduring fame were assured by 1,000 of Sam Colt’s percussion revolvers known variously as the Walker Pistol, Whitneyville Walker or Model of 1847 Army Pistol.

I will leave it to collectors and historians to debate how many .44 Colts were made earlier than this and how much influence Samuel Walker had on the design. Suffice to say, the U.S. in 1840 was similar to today in a few ways, yet in most, far, far

different. For example, we had a Congress that could make decisions. Problems were delt with substantively. The Indian wars of the 1830s-40s and the Mexican War of 1846 birthed the big .44 Colt revolver. Captain Walker wrote, “They [either the Walkers or a prototype] are as effective as a common rifle at one hundred yards and superior to a musket even at two hundred.” Targets were not paper bull’s-eyes.

The next event in the .44 caliber’s life was the French gunsmith Flobert placing a 5mm roundball in the mouth of a percussion cap in 1849. Thus was born the first almost practical self-contained metallic cartridge. American Horace Smith then began developing the idea.

Smith was also working with Daniel Wesson and Courtland Palmer in 1852 to produce a

lever- action repeating rifle called the Volcanic. It fired a conical bullet with a deep cavity in the base that was filled with fulminate priming compound. There was no powder. A copper washer with a cork disc in the center sealed the base of the bullet. Ignition was provided by the impact of a firing pin on the fulminate. This obviously didn’t work very well as there was no way to seal the breech against escaping gas.

Now we run into the most perplexing detail in the history of cartridge development. Smith and Wesson applied for a patent in May of 1853, which was granted in August 1854 (Patent No. 11,496) for an inside-primed, centerfire metallic cartridge! It was the solution to virtually all the problems of Smith, Wesson and Palmer’s repeating rifle, but the patent was not developed.

If the patent had been perfected there would have been few rimfires, no Winchester Repeating Arms Co., no Henry rifle or cartridge and perhaps no company called Smith & Wesson. The U.S.

military would have soon adopted powerful centerfire ammunition, possibly in a repeating rifle. Since all cartridge production would have occurred in the industrial Northeast, the timeframe is such that the Civil War might not have happened because the South could not manufacture the ammunition. Using muzzleloaders would have been hopeless. The South would have remained a powerful political force, gradually industrializing while forcing solutions and compromise on the real reasons for its disagreement with the North.

None of this happened of course, and a chap named Oliver Winchester acquired the assets of Smith, Wesson and Palmer’s partnership. Since the new company was producing the same rifle and ammunition as the old company, the cartridges guaranteed failure. Fortunately, Winchester had hired Benjamin Tyler Henry as his factory superintendent.

In the meantime, Smith and Wesson had succeeded in developing Flobert’s cartridge into a .22-caliber round with a pronounced rim filled with fulminate. Today it is called the .22 Short. It was fired in a small revolver that could not be sold until Colt’s patents on the revolving mechanism expired. Their revolver was introduced in 1857.

At the same time, B. Tyler Henry saw Smith & Wesson’s little .22 round as the solution to Winchester’s problems with his repeater. Henry supposedly first produced a .38-caliber cartridge, but his boss wanted something bigger. Who decided on the .44 caliber is not known. Some people have theorized it was the largest possible without redesigning the Volcanic’s repeating mechanism. At any rate, .44 it was, and in 1860 it was chambered in the soon to be famous Henry rifle.

The obvious question is why didn’t Smith & Wesson make a large caliber immediately after the success of the little .22 rimfire? Fact is, the company did, but it was only a .32 rimfire. Smith & Wesson, which also had to make cartridges for its revolvers since there was no cartridge industry yet, discovered that as calibers got larger, so did bullet weight and powder charge to produce useful velocities. This increased pressure, causing the thin copper-cased rimfire to expand back onto the breech face of the revolver. The cylinder would now either turn very hard or not turn at all. The Henry rifle, with its breech block moving straight rearward, was not affected.

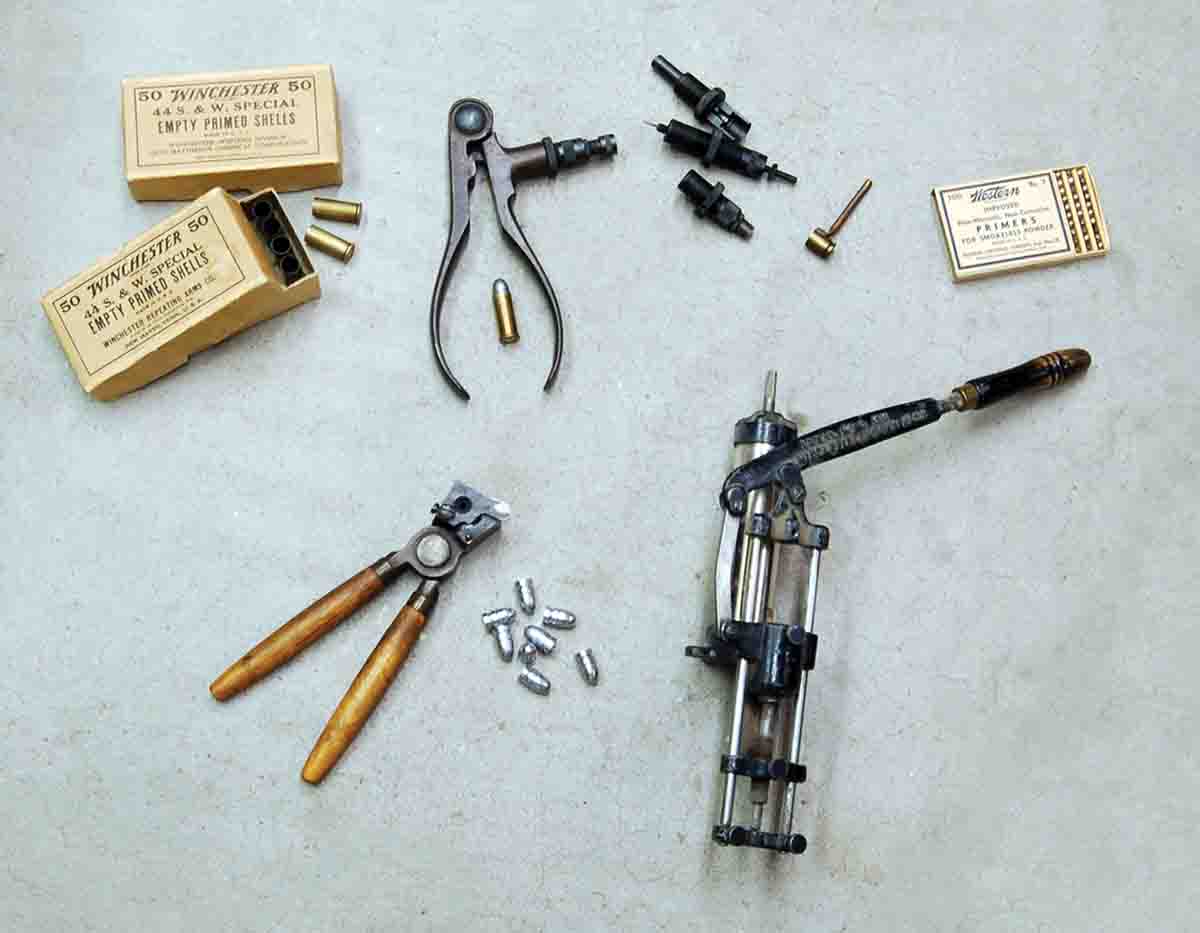

It was 1870 before Smith & Wesson offered its break-open Model No. 3 single action in .44 Henry rimfire. It is rumored that by this time .44 Henry cases were a bit stronger (drawn thicker) thus alleviating some of the swelling problem. This was not important, as a new round also became available in 1870. Called the .44 S&W; the word “American” was later added to the title to distinguish it from the .44 Russian of 1872. The .44 S&W was essentially the last version of the .44 Henry, but using a centerfire primer. It was the first outside-primed, reloadable, brass-cased revolver cartridge made in the U.S.

While the .44 S&W was not popular, Smith & Wesson didn’t really care because the Russian government had seen the Model 3 revolver and wanted about 150,000 of them! A longer .44-caliber cartridge was requested, which eventually used a groove diameter bullet seated inside the case. The .44 Henry and .44 S&W had the groove diameter of the bullet outside the case with lube smeared on the surface like a modern .22 rimfire. The new cartridge length was some .075 inch greater than the .44 S&W. The .44 Russian also became the premiere U.S. target cartridge in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

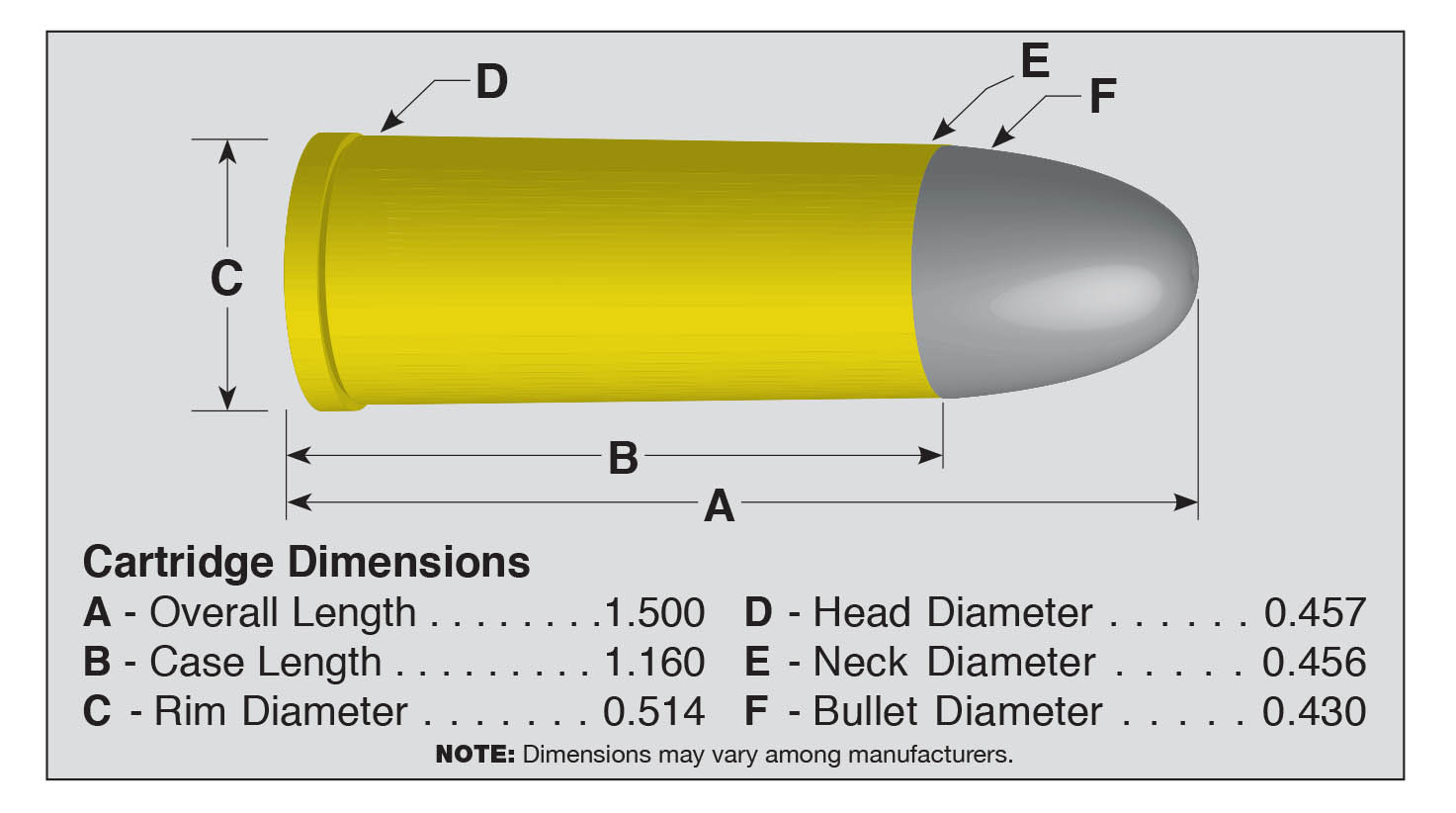

Nothing changed until 1907, when Smith & Wesson introduced a larger version of their Hand Ejector (solid frame, swing-out cylinder) revolver firing a round called .44 S&W Special. The revolver became known as the First Model Hand Ejector, New Century or triple lock.

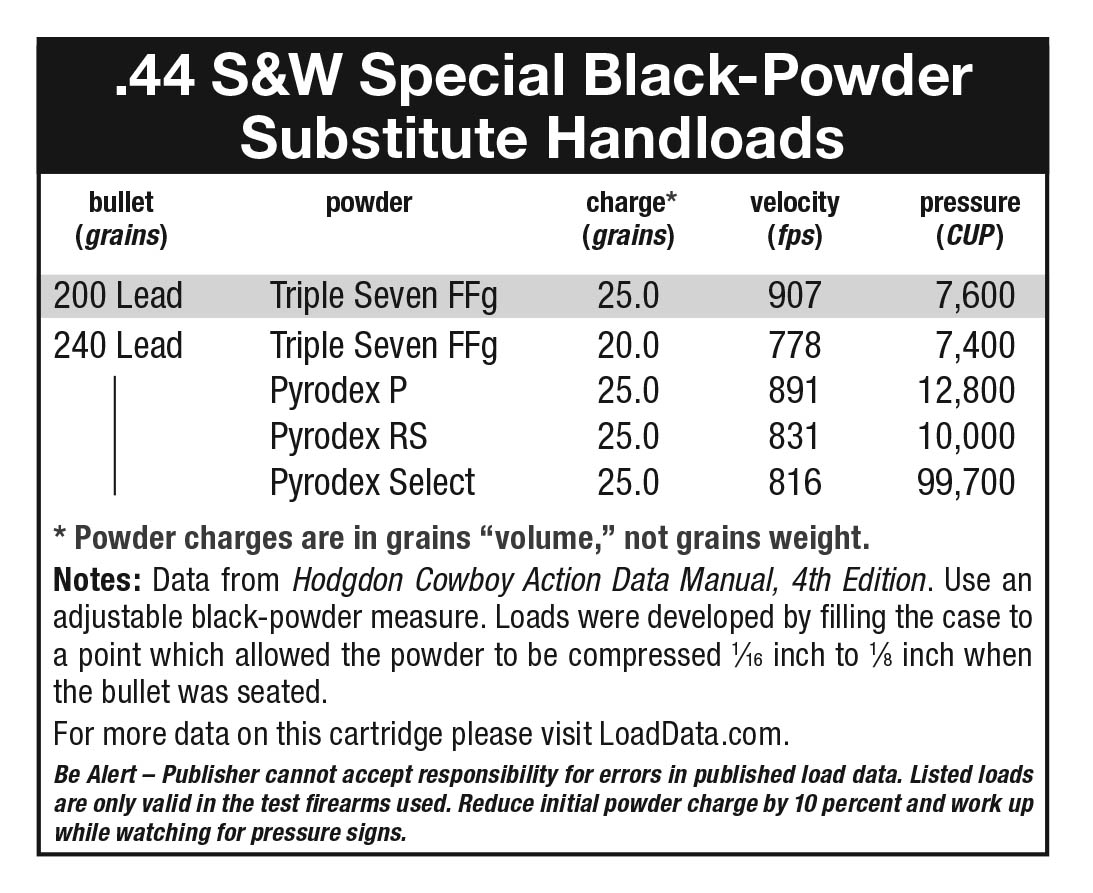

To create the .44 Special, Smith & Wesson simply lengthened the .44 Russian case about .2 inch. For comparison, the .44 Henry pushed a 200- to 210-grain bullet ahead of 22 to 25 grains of black powder. Muzzle velocities were hard to obtain at the time, but estimates indicate about 700 fps from a 6-inch barrel. The .44 American was loaded identically to the Henry. In the longer .44 Russian case bullet weight increased to 235 to 255 grains, but powder charge was 23 grains. Early authors suggested a velocity of 700 to 725 fps from a 7-inch barrel. In the still longer .44 Special, the original load used a 246-grain roundnose (as later became standard in the Russian) with the black-powder charge raised to 26 grains. Velocity was supposedly about 825 fps. Smith & Wesson now had a modern double-action revolver firing a powerful new cartridge. So why was it loaded with black powder in 1907? Also, why is this a .44 caliber (actually a .42) and not a smokeless loading of the .45 S&W Schofield of 1875? We will take this up, and much more, in the next column.