Winchester .32-20

Still Useful After All These Years

feature By: Terry Wieland | October, 19

At the venerable age of 146 and counting, the .32-20 Winchester (.32 WCF) is the most perplexing, infuriating and frustrating

The .32 WCF was introduced with the Winchester Model 1873, and subsequently adapted to the Colt single-action revolver. This provided a useful single- round, dual-purpose combination so beloved of denizens of regions far from a general store. Since that beginning, the .32-20 has been chambered in a wide range of rifles and handguns of varying descriptions, quality of design and manufacture. Therein lies both the secret of its longevity and the difficulty in writing about loading for it.

Since it originated as a black-powder round, all the early guns were weak by today’s standards. As well, while a round loaded with black powder will do equally well (or not so well) in a revolver or a rifle, the same is most

These days, factory .32-20 ammunition is generally hard to come by, there is not much variety when you do find it, and for the reasons outlined above, it’s pretty anemic. SAAMI standards for the .32-20 are geared to the capabilities of the weakest brethren, and current loading manuals adhere to those same pressure standards. What’s more, most modern load data for the .32-20 is intended for handguns, not rifles. Where such data is found, the powders listed are usually fast-burning handgun powders, not the slower-burning stuff that can provide more serious performance in a stronger action with a longer barrel.

The .32-20 has been chambered in some good, strong rifles, including (most famously) the Winchester ’92 and the single-shot Winchester Low Wall. Marlin also chambered it in its Model 1894, including a reintroduction in 1988 called the 1894-CL. There are probably some Stevens rifles on the excellent 44½ action to be found, and Savage made a range of rifles through the first half of the 20th century that, while not elegant, are certainly strong. For his 1989 article on loading .32-20 for rifles, Ken Waters’s test rifle was a Savage Model 23-C. Winchester discontinued its last .32-20, the bolt-action Model 43, in 1957. My rifle is a Low Wall of unknown vintage (the serial number is illegible) but in excellent condition, with a 26-inch octagonal barrel.

The little cartridge has several things going for it. One, brass is readily available from a number of makers – high quality and inexpensive – which is good because if you want to do any kind of serious shooting, you will have to load your own. For these tests, I used both Starline and Hornady brass, and both performed as well as expected. The cases use small rifle primers (in my case, Federal 205M), but small pistol or small magnum pistol can be used in a pinch.

On the cast-bullet side, Rainier Ballistics made a nice 100-grain copper-plated flatnose, and virtually every other bullet caster has something in .312/.313 inch that will work. I used a 100-grain flat-nose from the Missouri Bullet Co. that is intended for a cowboy action; the company offers the same bullet with special lube for use in black-powder guns. Altogether, there is no shortage of good components for the .32-20. Which brings us to smokeless powders.

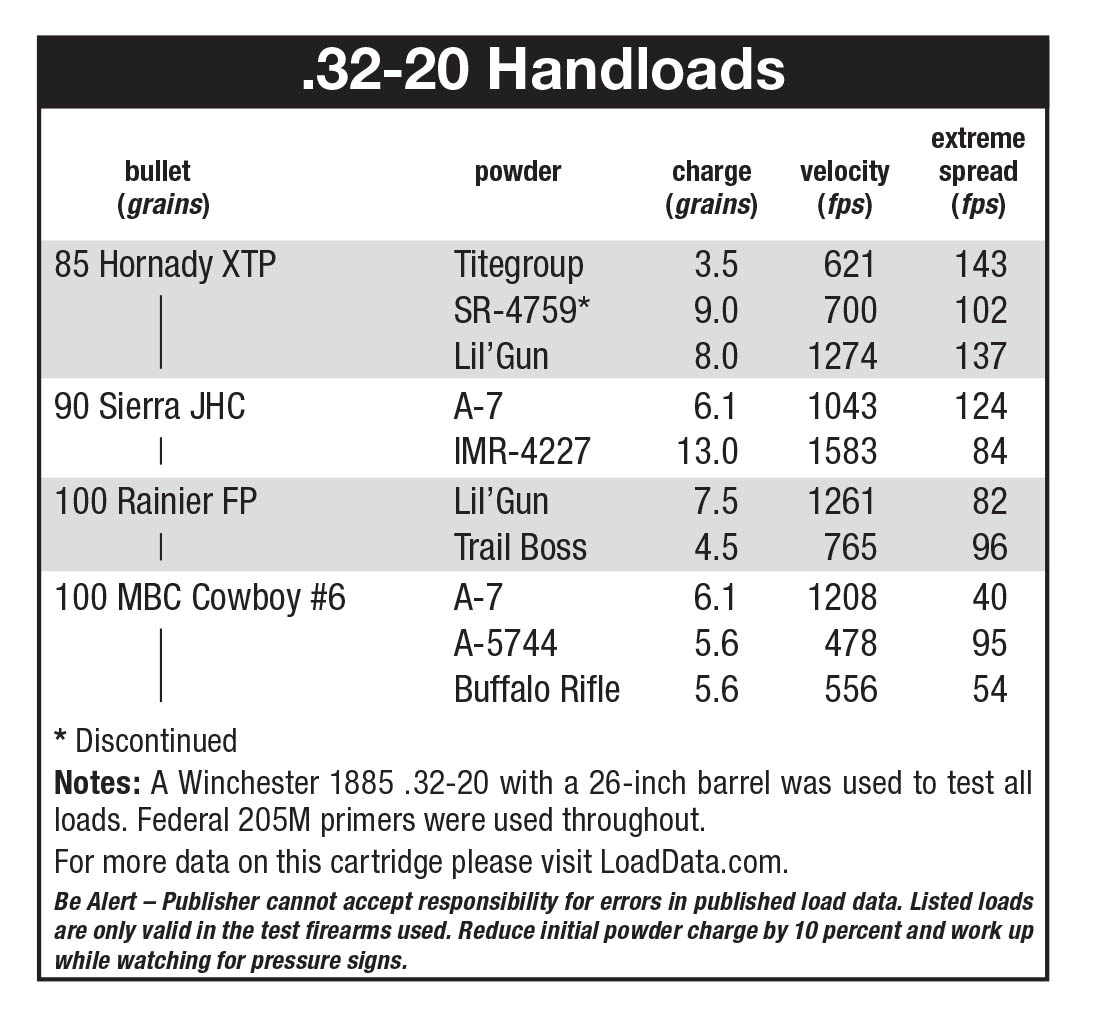

Traditionally, the powders recommended for .32-20 rifle loads are 4227 (either Hodgdon or IMR), 2400 and Unique. Old manuals rated SR-4759 as the equal of 4227, but it’s gone, and remaining stashes are too valuable for other purposes to waste on mass-produced plinking loads. IMR recommends Trail Boss to replace 4759, and I tried some. I also used both A-5744 and Shooters World’s Buffalo Rifle. Other new powders tested included Titegroup and Lil’ Gun, both from Hodgdon, and A-7.

Two immediate problems crop-ped up. First, some of the loads delivered unbelievably low velocities – so much so that I

Having fired about 30 rounds, most of them loaded either at or close to maximum charges listed in the available loading data, there was nary a pressure sign in any of the cases or primers. In fact, some were so low pressure they did not even form a gas seal, and the cases were blackened down to the base. At this stage, understandably, I was less concerned about accuracy than I was in simply finding some usable loads at decent velocities.

Western Powders’s A-5744, loaded using the old formula of 40 percent of capacity to the base of the bullet, propelled the 100-grain cast bullet at such a low velocity as to be useless. Shooters World’s Buffalo Rifle, which performs the same function as A-5744, delivered comparable velocities using the same light-load formula. It should be noted this is NOT a published Shooters World formula or load. However, neither A-5744 nor Buffalo Rifle is intended to give high velocities, so I ended the experiment right there. The .32-20 is not a cartridge for which you need to seek out light loads; quite the opposite.

A comparison load with SR-4759, just to test old formulae (in this case, a load from Lyman Reloading Handbook, 43rd Edition) proved nothing except that it was not worth pursuing. Titegroup was another experiment. It’s Hodgdon’s challenger to Bullseye, used in minute amounts in pistol cartridges. With 3.5 grains listed as a maximum load, any increase would need to be in excessively tiny increments. Since I got only 621 fps with it out of the 26-inch barrel, compared to Hodgdon’s listed velocity of 961 fps from a 5.5-inch barrel, it did not seem worth pursuing either. The thinking on that odd circumstance was that the long barrel might actually be slowing down the bullet as it neared the muzzle and pressure dropped.

Trail Boss is the powder intended by Hodgdon to replace SR-4759, mainly (as the name suggests) in cowboy action shooting. The usual prescription is to fill the case to the base of the bullet, while being careful not to compress it. With the 100-grain Rainier bullet, this came to 4.5 grains. It gave a respectable cowboy velocity of 765 fps, but there was really nowhere to go from there. That, by the way, exceeded Hodgdon’s maximum of 2.8 grains for a 115-grain bullet while falling short of the company’s published velocity (765 vs. 830 fps).

Western Powders gives a maximum load of 6.1 grains of A-7 with either a 90- or 100-grain bullet. As seen in the table, the results were not at all what I expected, with the same charge giving a higher velocity in the heavier bullet. Since the cast bullet was a tighter fit in the bore, that probably explains it.

The results that came back were enough to make one back off quickly. All four not only exceeded SAAMI maximums for .32-20 ammunition, they exceeded proof pressures for the cartridge. Ron’s explanation for the lack of adverse pressure signs in my rifle – one of the stronger actions for which the .32-20 was chambered – is that today’s brass and primers can stand considerably higher pressures than the brass and primers available when the .32-20 was hatched. That does not mean any old action will also take such extreme pressures. With the .32-20, it pays to adhere to SAAMI specs and published maximums.

On the bright side, I did get some gratifying accuracy with the Low Wall. With its original-issue open sights, shooting groups is inexact even at 50 yards, but the group shown is certainly the kind of accuracy one could write home about, and delivered by the Sierra 90-grain JHC, at that. One should remember, when using that bullet, that it was intended to perform its best at velocities delivered by the .32 H&R Magnum. Even if one could safely exceed 1,500 feet per second with it, its terminal performance might be impaired. The same is true of the Hornady 85-grain hollowpoint.

In a good rifle like the Marlin 1894-CL, Winchester ’92 or the Low Wall, combined with good bullets like these, the .32-20 fits into a very useful niche as a small-game or pest rifle. The original purpose of these tests was to provide a starting point for developing decent rifle loads with some modern powders, not to set velocity or accuracy records. With that in mind, I suggest working with 4227, Lil’Gun or A-7, trying both the Sierra 90- and Hornady 85-grain jacketed hollowpoints, or any good 100-grain cast bullet.Although it flies in the face of modern thinking, where the objective is usually to either get pin-point accuracy or sky-high velocities, one should really approach the .32-20 in a different frame of mind. Its maximum effective range of little more than 100 yards, combined with the fact that many of the old rifles chambered for it will not readily accept a scope, means that high velocity or a flat trajectory really don’t alter its overall capabilities.

At 146 years of age, the .32-20 deserves the respect and consideration we usually accord the elderly, although I will say of mine, it sure likes to be taken out for a nice walk in the woods. And what’s a walk in the woods without a gun in your hand?