Learn To Reload (Handloading Basics)

Choosing Bullet

feature By: John Haviland | October, 19

Everything rides on the bullet – the success of a hunt, a tight cluster in the bull’s-eye of a target or the clang of a steel plate at long distance. Before a bullet is sent on its flight to meet those expectations, a handloader must ensure it’s correct for the job and handloaded properly so it can perform its intended job.

Bullet Types

Swaged-lead bullets and cast bullets are not the same. Bullets could be cast out of plain molten lead. However, lead flows poorly and produces incompletely formed bullets, and they would have the same soft Brinell Hardness Number (BHN) of 5 as swaged-lead bullets. Correctly cast bullets made with lead alloyed with tin increase the flow of the molten lead alloy to produce fully formed bullets, and antimony is used to

Companies that describe their bullets as “hard cast” could be referring to anything cast of lead alloy. It’s better to look for the BHN of bullets. Missouri Bullet Company’s cast lead rifle and Action Series handgun bullets have a BHN of 18 while its Cowboy Series bullets have a BHN of 12.

Plain base bullets with a BHN of about 12 can be fired up to around 1,300 fps with good accuracy and little to no leading. One evening this past spring I shot a hundred .30-30 Winchester cartridges through a Winchester Model 94. The cartridges were loaded with 150-grain plainbase bullets cast of lead alloy with a BHN of 13 and a muzzle velocity of 1,250 fps. The few streaks of lead clinging here and there on the rifling lands were easily brushed out.

Cast bullets with the same BHN of 12 fired at higher velocities require the addition of a gas check (a copper cap on a bullet’s base), which strengthens the base and protects it from the eroding effects of powder gases. Using gas checks, I shoot 150-grain bullets cast of lead alloy with a BHN of 12 at a muzzle velocity of 1,927 fps from my .30-30. Three-shot groups measure a touch over an inch at 100 yards and the bore remained clean of lead.

Bullet jackets do vary. Berry’s Superior Plated bullets start with a lead core tumbled in an electrically-charged bath of copper ingots that forms a jacket through electrolysis. Berry’s, though, warns to “… stay away from magnum velocities when loading plated bullets.” Jackets are also electroplated on Speer Gold Dot and Federal Fusion bullets. However, resulting jackets are as thick as .038 inch to withstand even the highest velocities.

Gilding metal, with a composition of 95 percent copper and 5 percent zinc, is the standard bullet jacket material. It is relatively soft and ductile to form jackets and is to an extent self-lubricating and less likely to foul bores than plain copper. Cores inserted in these jackets consist of lead, or lead alloyed with a small percentage of

Single-metal bullets may be made of brass, copper or gilding metal. These bullets are relatively long for their weight. Some of these bullets, such as the Barnes Triple-Shock and Hornady GMX, feature grooves around their shank to reduce bearing surface to lower pressure on firing.

About 10 years ago, most any bullet would stabilize when fired through a rifle with a standard rifling twist – but long-range shooting has ushered in bullets as long as a newly sharpened No. 2 pencil. The common 1:12 rifling twist for a .223 Remington stabilizes bullets weighing up to about 60 grains. But longer 69- to 80-grain bullets require at least a 1:8 twist. Check a bullet’s recommended twist rate to confirm it’s compatible with your rifle.

Bullet Seating

Basic bullet seating should be a simple process. All that’s required is to seat a bullet deep enough in a case to match the cartridge length of that particular bullet as listed in a handloading manual. That length is usually shorter than the specified maximum measurement, and such a cartridge will fit in most any gun chambered for it and produce acceptable accuracy.

The chamber leades of rifles vary some because of manufacturing tolerances – and perhaps greatly due

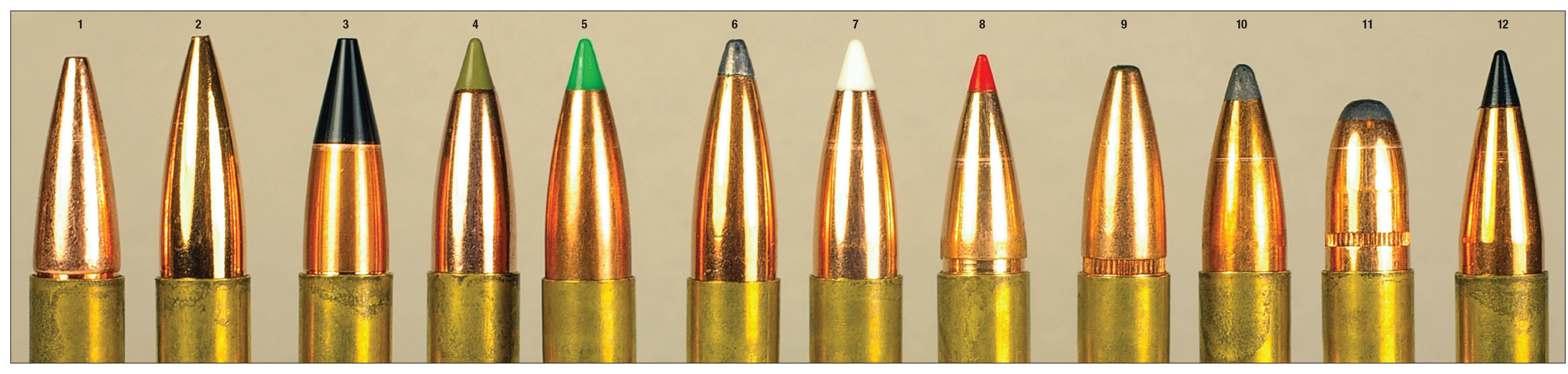

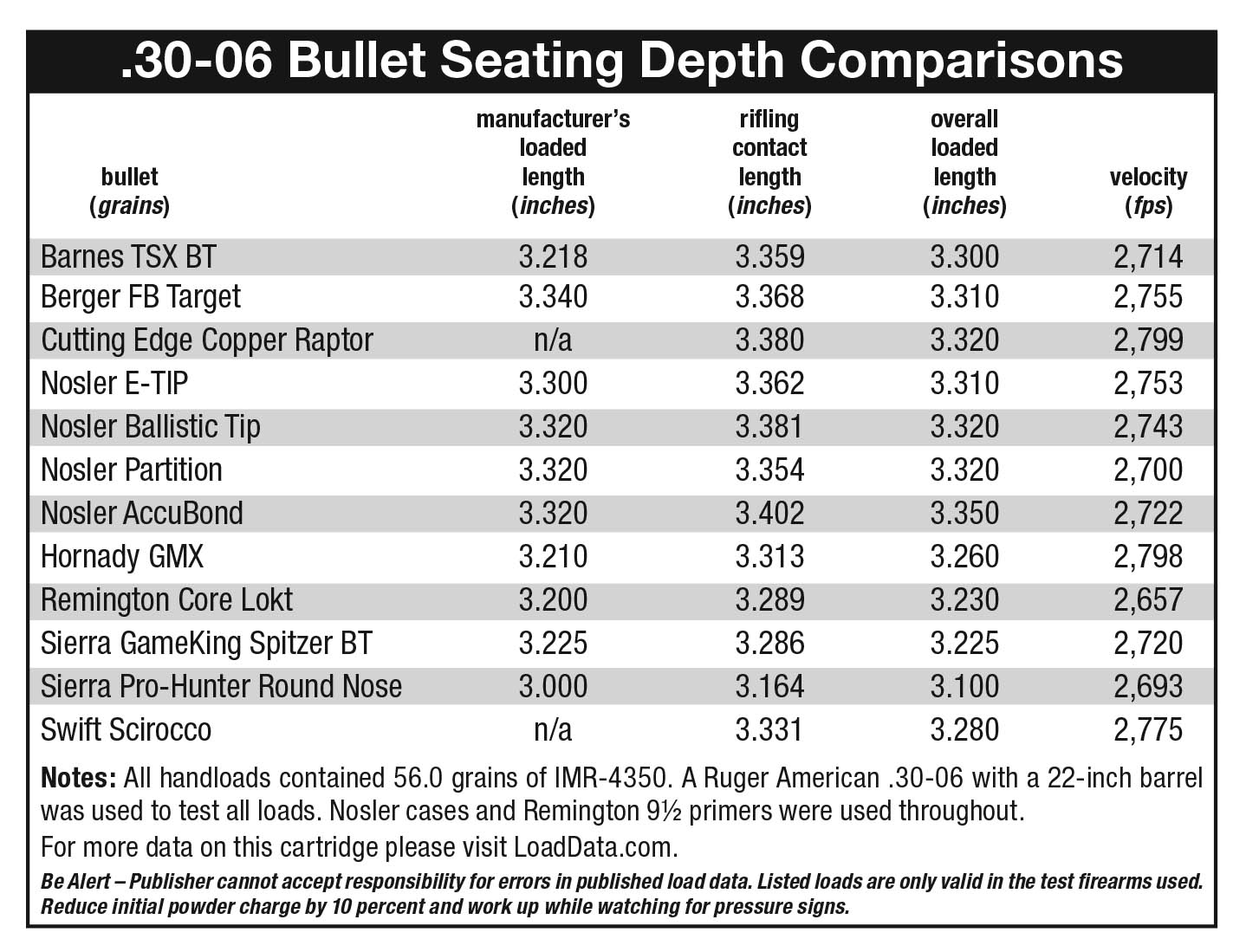

To illustrate the various seating depths of different bullets of the same caliber and weight, I set 12 assorted .30-caliber 150-grain bullets in contact with the start of the rifling of a Ruger American .30-06 and measured the cartridge lengths. The easiest way to determine where the bullet’s ogive contacts the rifling is with a Hornady Lock-N-Load O.A.L. Gauge. I screwed a modified .30-06 case onto the front of the gauge, placed a bullet in the case mouth and inserted the case snugly into the rifle’s chamber. A plunger inside the gauge handle is slid forward through the case to push the bullet into contact with the rifling. With the plunger locked in place, I removed the case from the chamber, placed the bullet back into the case and measured the cartridge length.

The accompanying table shows the cartridge lengths varied up to .238 inch between the different bullets. Cartridge length of seven of the bullets exceeded the .30-06’s established maximum cartridge length of 3.340 inches. The Ruger magazine has enough room to accept cartridges with a length up to 3.385 inches.

For trouble-free functioning, bullets are best seated short of the rifling. In a bolt action, a good place to start bullet seating depth is .030 inch short of touching the rifling. Barnes Bullets states its X-Bullets shoot most accurately when seated .050-inch short of the rifling. Bullets seated excessively deep in a case do reduce powder capacity and raise pressure.

The accompanying table also lists cartridge lengths recommended by manufacturers for their bullets, except Cutting Edge and Swift, which do not include loaded cartridge lengths for their bullets. These cartridge lengths placed the bullets well short of contacting the rifling in the Ruger. I seated the bullets in the chart about .050 to .060 inch from contacting the rifling.

Powder charges also vary between bullet companies for bullets of the same caliber and weight. Some of this is due to testing with different brands of primers and cases. Bullet length and bearing surface are also considered. For the .30-06 shooting the listed 150-grain bullets, maximum charge weights of IMR-4350 varied from 59.9 grains in the Hornady Handbook of Cartridge Reloading, 9th Edition down to 56.5 grains in Swift’s

The seating depth of five of the bullets were set to the rifle’s accuracy sweet spot. Three each of the Barnes TSX BT, Cutting Edge Copper Raptor and Nosler Ballistic Tip grouped close to .80 inch at 100 yards. Three Nosler E-Tips grouped in .25 inch and three Sierra Pro-Hunter roundnose bullets grouped into .63 inch. If bullets fired from your rifle shoot acceptably well, varying their seating depth a touch longer or shorter may well reveal that sweet spot.

Just as important, seating bullets straight in case necks aligns them with the centerline of the barrel bore. Bullets .005 inch or more off-center can cause accuracy to go downhill. A few small steps help seat bullets straight. Make sure the inside of the die and bullet seating stem are clean. When adjusting a seating die, place a case in the press shellholder and pull the handle down to fully raise the case. Screw the die down until it touches the case, then back the die off one turn. At that position, the bottom of most dies are close to the shellholder. As it so happens, a nickel placed on top of a raised shell holder firmly contacts the bottom of an RCBS .30-06 seating die raised one turn from contacting a case. The pressure from the nickel takes the play out of the die threads to ensure the die is straight in the press. Turning down the die lock ring firmly on the top of the press and tightening its setscrew maintains that alignment.

Determining if bullets are seated ruler-straight requires a tool like the Sinclair Concentricity Gage, RCBS Case Master Gauging Tool or Hornady Lock-N-Load Concentricity Tool that measure bullet run-out to thousandths of an inch. The Hornady tool allows straightening crooked bullets by turning a cartridge in the tool to where the dial indicator registers its lowest point. Turning in a thumbscrew on the tool puts pressure on the opposite side of the bullet to straighten it.

The correct amount of crimp varies. Applying too much crimp bulges a case or crumples its neck. Whether rifle or handgun, load its magazine full and fire all but the last cartridge. Measure that cartridge to check if its length has remained unchanged; apply more crimp if the bullet has moved.

Seating bullets is the final step in ammunition assembly. With knowledge and guidance about particular bullets, their seating depths and possibly crimping to lock them in place, you can rest assured all your hopes riding on the bullet with be realized.