9mm Luger (Pet Loads)

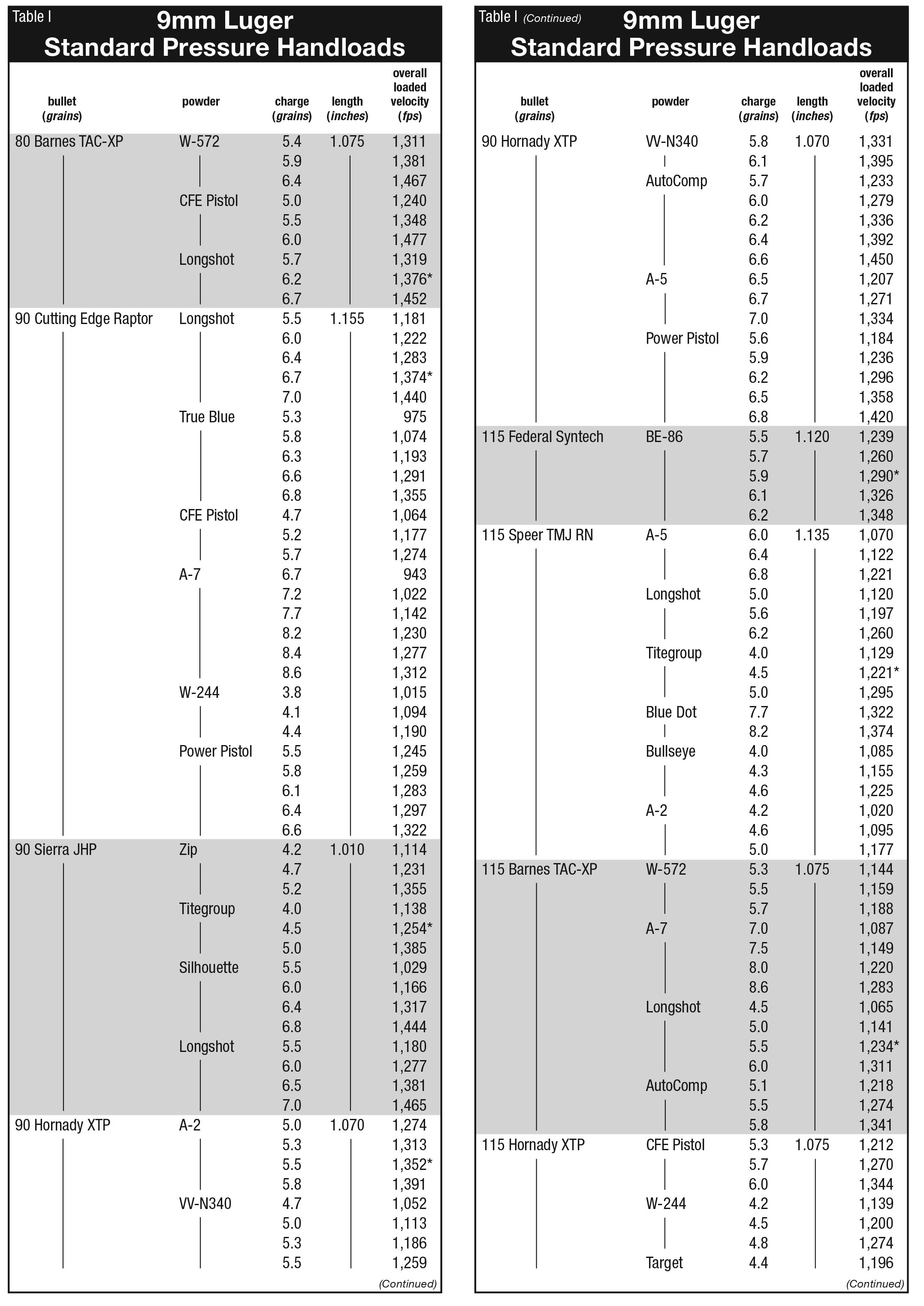

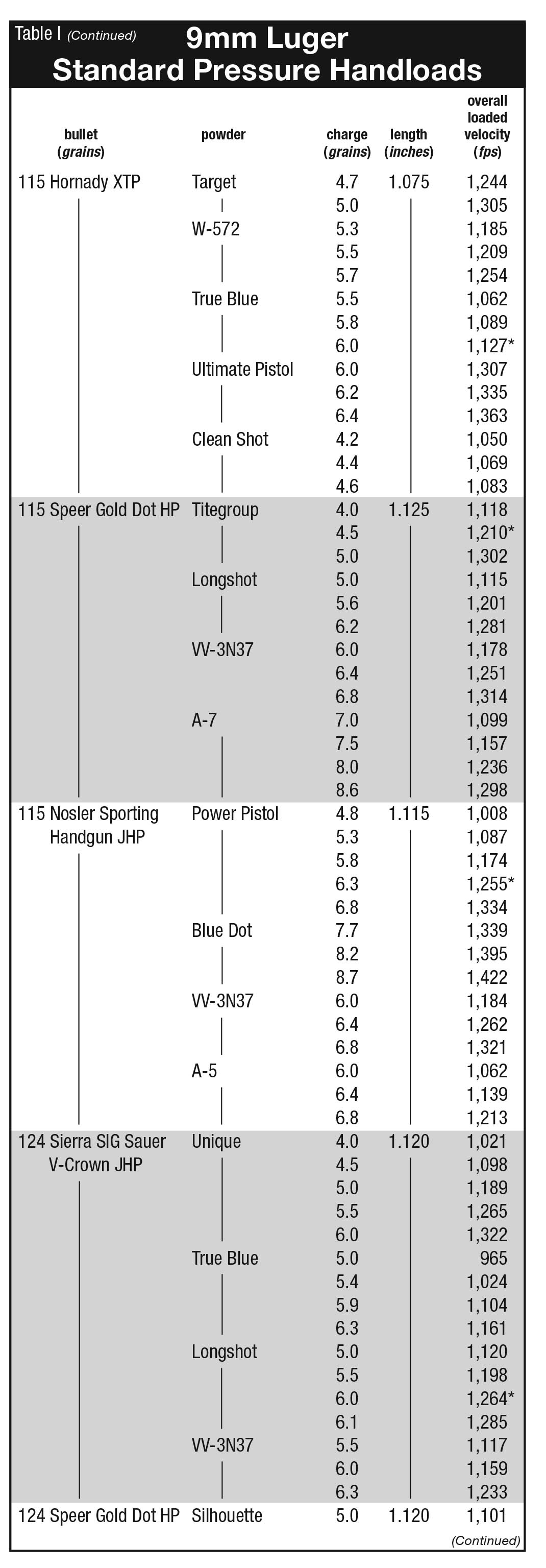

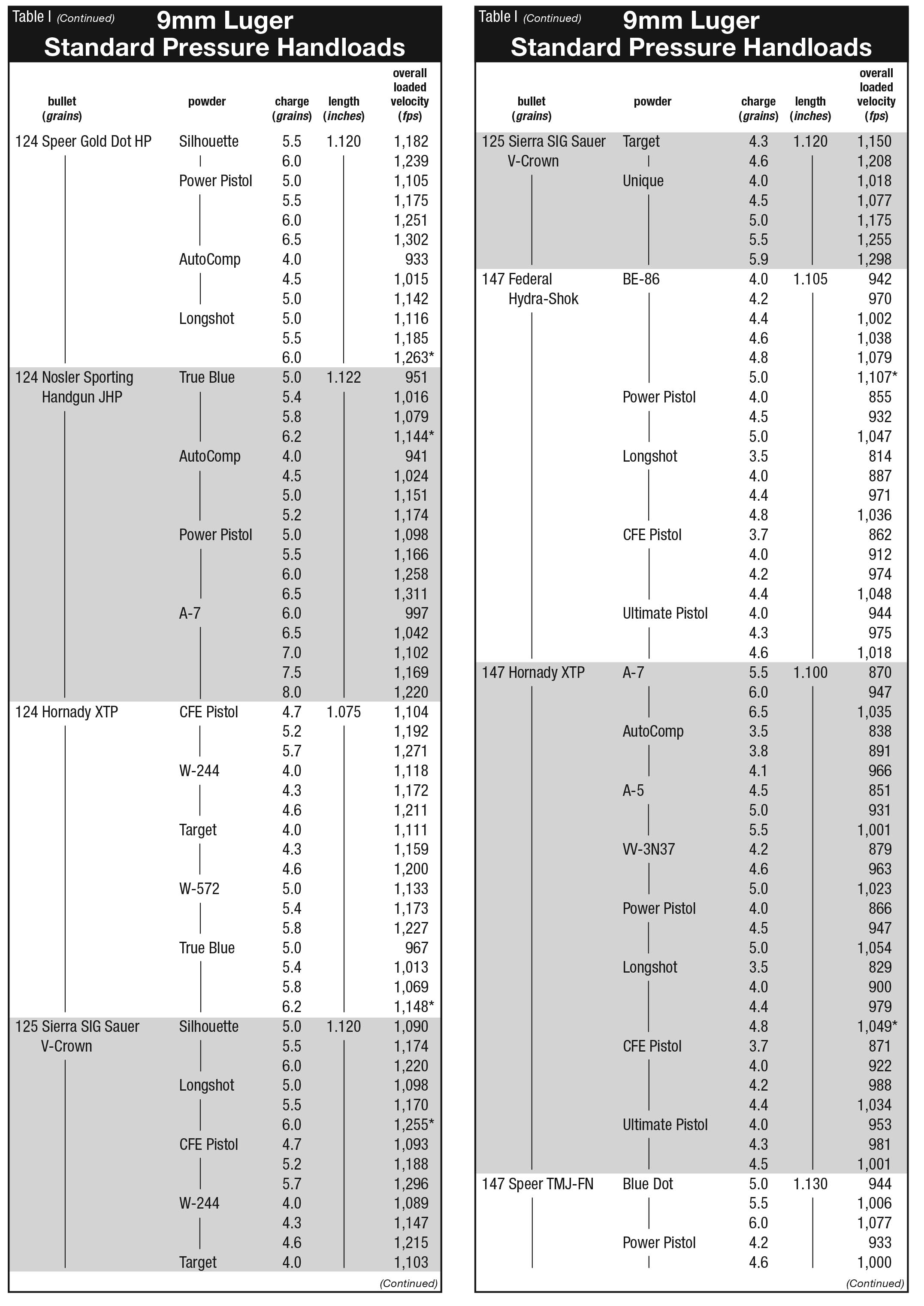

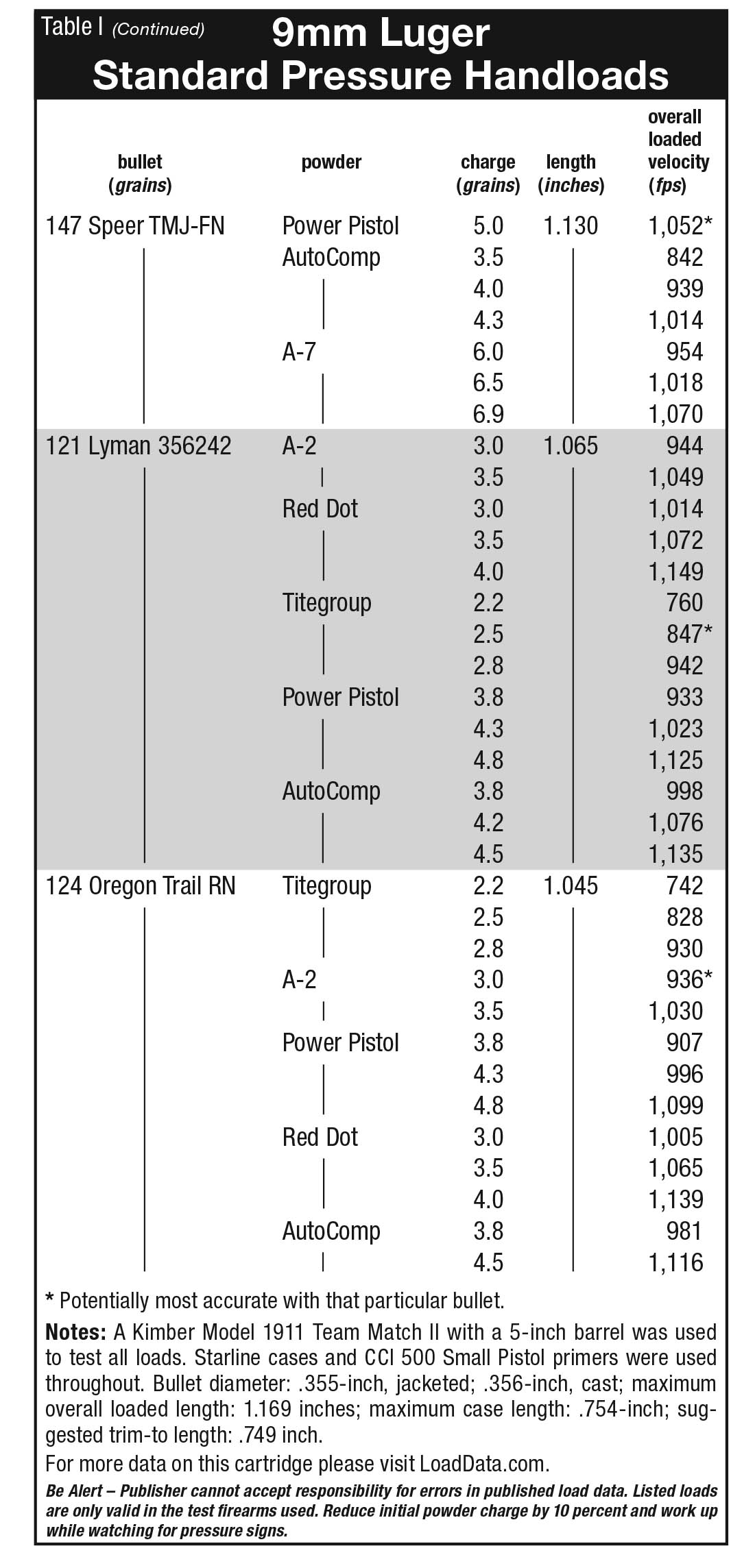

Standard Pressure Loads

feature By: Brian Pearce | October, 19

The Luger P08 “toggle-locked” pistol was developed around 1898 and first chambered in .30 Luger (7.65x21mm Parabellum); however, by 1901 the designer of the gun and cartridge, Georg Luger, modified that case to create the 9mm Parabellum that was also chambered in the Luger pistol. Incidentally, the word “Parabellum” is taken from the Latin phrase Si vis pacem, para bellum, which loosely translates into “prepare for war.”

While that gun and cartridge combination was almost immediately adopted by the German Navy and Army, it wasn’t until after World War I that its popularity really began to grow. With widespread acceptance in Europe and other parts of the world, it was only a matter of time until it gained favor in the U.S.

Following World War II, inexpensive surplus ammunition became available, but the FMJ roundnose bullets that typically weighed between 115- and 124-grains produced comparatively little shock and limited the cartridge’s effectiveness for hunting, defense or law enforcement work. Furthermore, there were very few pistols available to U.S.

During the 1960s, Super Vel Ammunition (as operated by Lee Jurras) pioneered a 90-grain JHP load at around 1,400 fps. Winchester followed in 1979 with its 115-grain Silvertip bullet at 1,255 fps. These loads helped put the 9mm on its way to becoming a viable defense and law enforcement cartridge, but that was just the beginning. Today the selection of premium defense and law enforcement factory loads (including +P options) is nearly endless and includes expanding monolithic bullets as light as 95 grains at over 1,500 fps, various 115- to 124-grain expanding bullets at velocities around 1,400 and 1,300 fps, respectively, and subsonic loads that usually contain 147-grain bullets at around 1,000 fps. Expanding bullet technology has played a huge role in making the 9mm a viable defensive round, which in addition to being offered in factory loads, are readily available as handloading components.

The three most common bullet weights are 115-, 124- and 147- grains, which are generally listed by U.S. manufacturers at around 1,190 fps, 1,150 fps and 990 fps, respectively (velocities do vary slightly from various manufacturers). It is important to understand that these loads are almost always at least six percent to 10 percent below industry maximum average pressures, which leaves a proper margin of safety. Using the correct combination of

For clarification, the 9mm NATO often utilizes a 124-grain FMJ RN “Ball” bullet at 1,250 fps, which is loaded to higher pressures than 9mm Luger commercial ammunition and is listed with a maximum average pressure of 36,500 psi (proof loads are 45,700 psi). As a result, surplus 9mm NATO ammunition is not recommended for all pistols, particularly vintage guns. Check with firearms manufacturers to determine if they recommend using these higher pressure loads in a given model.

This brings us to 9mm Luger +P loads that operate at a maximum average pressure of 38,500 psi, and again are not recommended for all pistols. Some ammunition companies list 9mm +P+ loads, which are not regulated by SAAMI and are loaded to proprietary pressure levels and velocities, so are only recommended for select guns.

With so many different case manufacturers, there is a huge difference in their construction. In examining cases from more than two dozen manufacturers, including foreign and domestic militaries, the weight and water capacity differences are significant.

While there are variances among U.S. manufactured commercial cases, the differences are not great. Nonetheless, there are differences in construction, wall thickness and taper and flash hole size, all of which can change pressures of a given load. When handloading mixed cases made in the U.S., maximum loads should generally be avoided. To achieve top accuracy, uniform pressures, etc., use cases that are of one lot from one manufacturer. If surplus military cases are used, the crimped-in-place primers will need to removed with the aid of a decapping die or rod. Next, the primer crimp will need to be removed before attempting to insert new primers. There are several good tools for this job and include versions that cut the crimp out or swage the primer pocket back to a configuration that permits a new primer to be easily seated.

Some cases exhibit significantly thick walls, which is generally not a problem when using light and standard weight (up to 124-grain) bullets; however, when seating the comparatively long 147-grain bullets, they can cause the case to bulge at the bottom of the bullet, resulting in the cartridge being out of spec – and often will not chamber.

For this article, new Starline cases were used, which are high in quality and readily available factory direct. Their dimensions permit the use of all bullet weights, including various 147-grain versions. Incidentally, Starline offers cases marked “9mm” and “9mm +P,” but their construction is identical. They are so marked only to differentiate between loads.

The 9mm case is slightly tapered; however, it works perfectly (thankfully) with carbide sizing dies, with RCBS dies used to develop the accompanying data.

In spite of its tapered case with a base diameter of .391 inch and a maximum neck diameter of .380 inch, the 9mm headspaces

In measuring the crimps of more than a half-dozen factory loads using a blade caliper, virtually all measured between .370 and .373 inch. The one exception was the Cutting Edge PHD load that measured .379 inch. Handloads were crimped between .372 to .373 inch with all conventional jacketed lead-core bullets and cast bullets; the Cutting Edge 90-grain Raptor was crimped to .379 inch. While a taper crimp can be applied as the bullet is seated, this can result in damage to bullets, shaved lead, reduced accuracy, etc. It is suggested to always seat the bullet to the correct overall cartridge length and apply the crimp as a separate step. Maximum case length is .754 inch; suggested trim-to length is .749 inch.

As indicated, the 9mm has a very small powder capacity. As a result, seating bullets deeper, or to a shorter overall cartridge length than listed, will result in greater reduction in powder capacity and a sharp increase in pressure. In one test, bullets were seated to a standard industry overall length with powder charges established for a load that was within pressure guidelines. The same bullet was then seated just .040-inch deeper with no other changes to the load, and resulted in a 6,000 psi pressure increase – an overload!

It is common for handloaders to use data developed for a given jacketed bullet, but substituted with a bullet from another manufacturer that is of the same weight. This practice will almost always result in changes in velocities and pressure. These changes may only be minor, but in extreme instances it can result in as much as 6,000- to 8,000- psi pressure changes. Some of the factors include bullet base design, shank length, or bearing surface, and jacket material.

Data for the monolithic expanding Barnes TAC-XP and Cutting Edge Raptor HP is specific to those bullets. Powder charge weights developed for other bullets of the same weight should not be interchanged.

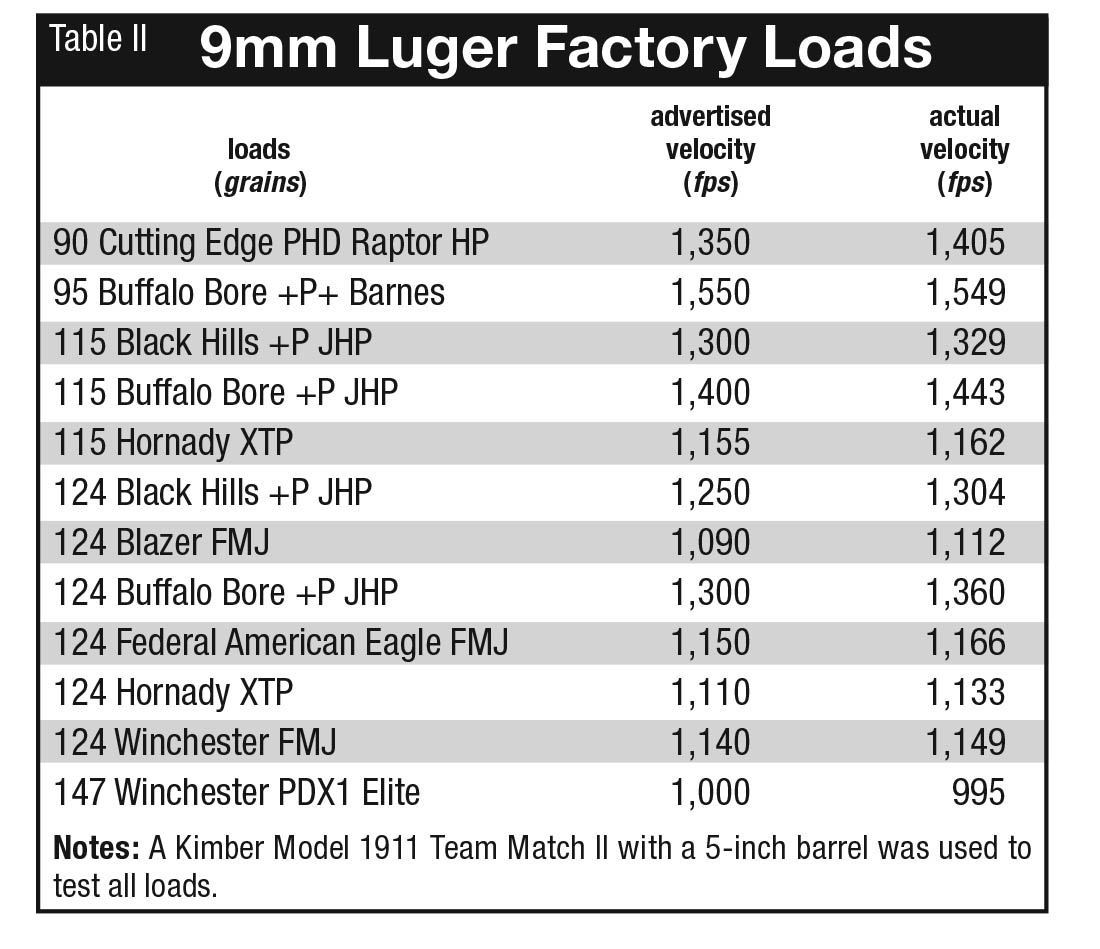

Having worked up many handloads in a Kimber 1911 Team Match II 9mm, that pistol was again selected to develop the accompanying data. This gun is accurate, features fully adjustable sights, a SAAMI chamber and is excellent for checking loads for velocity, function, etc. It should be noted that the 5-inch barrel produced greater velocities than shorter barrels so common on other 9mm pistols.

As indicated, 9mm bullets have been improved to achieve reliable expansion, making a rather marginal cartridge far, more effective. A few examples include the Nosler Sporting Handgun JHP, Speer’s bonded Gold Dot HP, Hornady’s XTP and various Sierra JHP bullets, Federal has recently begun offering its 147-grain Hydra-

Shock bullet as a component to handloaders, which has earned a reputation for reliable expansion and terminal performance. In my tests it produced excellent accuracy and is a great choice for subsonic loads. Expanding monolithic bullets include the Barnes TAC-XP constructed of 99 percent- plus copper and the Cutting Edge 90-grain Raptor HP constructed of pure (145 series) copper and features four pre-cut petals that break off soon after entry and cause severe tissue damage while the remaining “solid” shank penetrates deeply.

With the rising popularity of suppressors, many shooters are choosing subsonic loads, which generally push a 147-grain bullet to velocities between 980 fps to 1050 fps from common barrel lengths. However, these loads should not be used in guns with barrels that exceed 10-inches, due to the risk of sticking a bullet in the bore. The 9mm has a very short pressure curve, with peak pressure usually occurring as the bullet exits the case. With this fact combined with the greater bearing surface and resistance in the barrel of various 147-grain bullets, there just is not enough energy to reliably push them out of longer barrels.

When shooting valuable vintage guns such as the Luger P-08 and submodels, cast bullets are highly recommended to prevent premature or undesired barrel wear. The Oregon Trail 124-grain RN is economical while 121-grain bullets from Lyman mould No. 356242 offered an accuracy advantage. At velocities of around 1,050 to 1,150 fps, they function reliably in most guns. Not all modern gun manufacturers recommend cast bullets in their guns. The problem stems from barrels that are prone to leading or are fired with improper load combinations that cause leading. If barrels are not cleaned prior to using a full-power jacketed bullet load, pressures can spike and cases can rupture, which may cause damage to the gun.

In addition to the 9mm benefiting greatly with modern expanding bullets, improved powders have increased its accuracy and velocity, with select versions being especially clean burning. In regard to extreme velocity spreads and accuracy, the differences were often rather small. Nonetheless, top accuracy powders often included Hodgdon Titegroup, Accurate No. 2, Ramshot Zip, True Blue, Vihtavuori N340, VV-3N37, Alliant Power Pistol, BE-86 and IMR Target. For enhanced velocity loads, Winchester 572, AutoComp, Hodgdon CFE Pistol, Longshot, Alliant Power Pistol, BE-86, Unique, Ramshot True Blue and VV-N340 are good choices.

Most standard small pistol primers from CCI, Federal, Winchester and Remington feature cups designed to handle pressures up to 40,000 psi, and in some instances higher. With typical powder charges for the 9mm being rather small, magnum primers are not necessary, nor recommended, as they increase chamber pressure and extreme spreads while only bumping velocities minimally. CCI 500 primers were used to develop the accompanying loads.

While the 9mm can be loaded easily on single-stage presses, the case is small and can be difficult to manipulate in and out of shell holders, etc. Since it is generally fired in large quantity, it is suggested to develop test loads on a single-stage (or turret) press, but after testing is complete, large quantities of ammunition are best assembled on a progressive press, such as those offered by Dillon Precision, Hornady, etc. Regardless of the loading method, use a high-quality powder measure designed specifically to throw the small charge weights associated with the 9mm.

With a huge selection of powders and bullets available for the 9mm, handloaders can reach new levels of performance.