Cartridge Board

.300 Winchester Short Magnum

column By: Gil Sengel | August, 17

Nevertheless, many riflemen felt improvement was possible by increasing both velocity and bullet diameter. This would require a larger case diameter to accommodate larger charges of powder and allow maintaining an adequate shoulder for headspacing as bullet diameter got larger. Then something strange happened.

In 1905, English gunmaker Holland & Holland introduced a case slightly larger in diameter for a round called the .400/.375 Belted Nitro Express. Instead of headspacing on the rim or shoulder, it used a wide belt just forward of the extractor groove. It appears this idea was borrowed from artillery shells. In 1912, this belt was slightly modified to create the .375 H&H Magnum cartridge. The idea worked, but nobody else seemed interested, preferring instead to just make much larger bottleneck cases, like the .404 Jeffery and .416 Rigby.

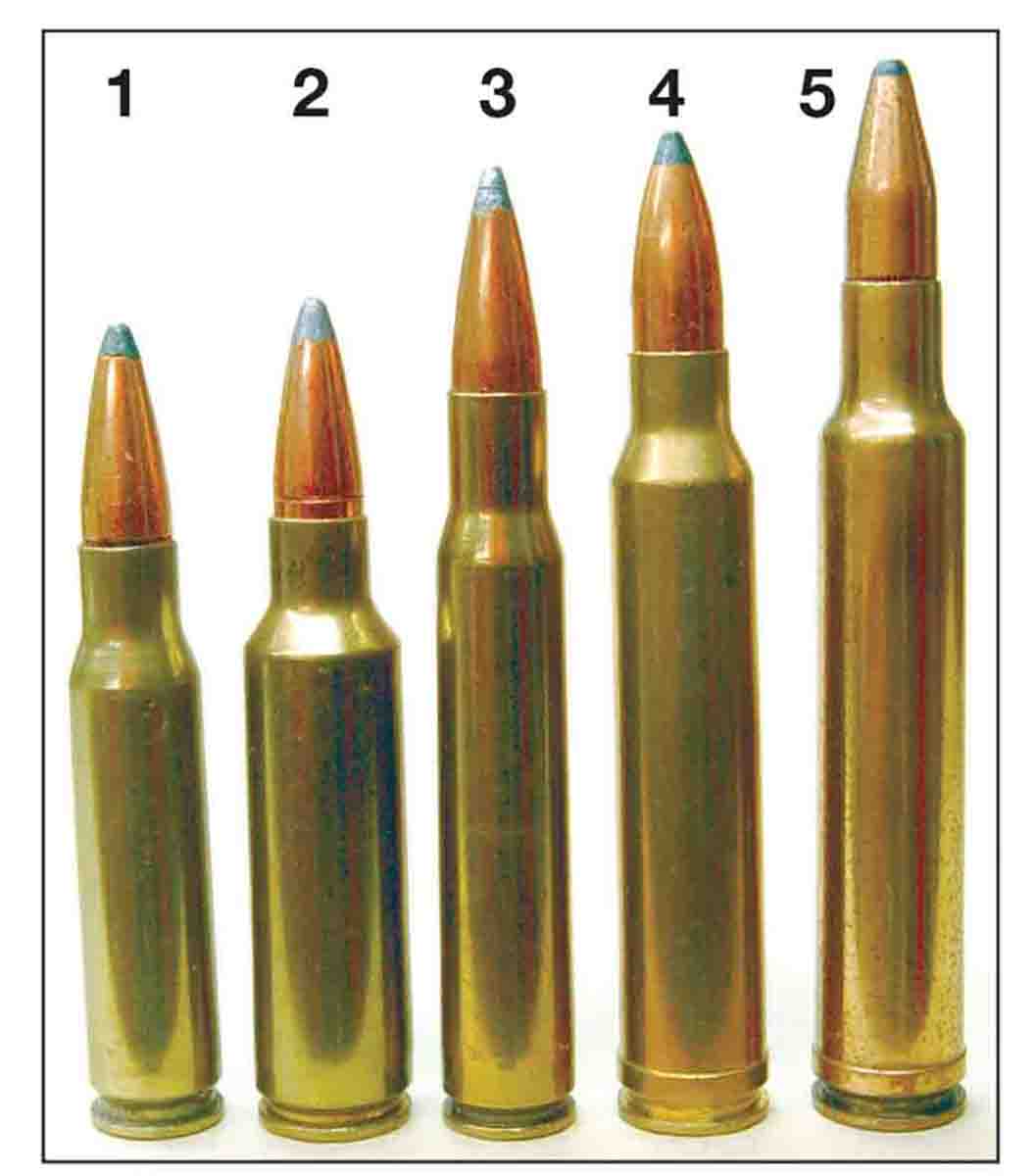

The only enthusiasts who eventually took to the belted case were American wildcatters, with Roy Weatherby leading the pack. By the 1950s, major U.S. companies were turning out new cartridges using the belted case, but they used a 2.5-inch long case, rather than the 2.850-inch H&H case. The reason was that powder development had progressed to the point where greatly increased case capacity was not thought necessary. The shorter case also allowed these rounds to fit in a “standard” .30-06 length bolt action.

Forty years later, benchrest shooters discovered that in some instances short, fat cases gave slightly more uniform shot-to-shot velocities than smaller diameter cases of equal volume. Theoretically, this should mean smaller groups. It is more important in long-range target competition, because velocity variation yields a change in vertical bullet impact.

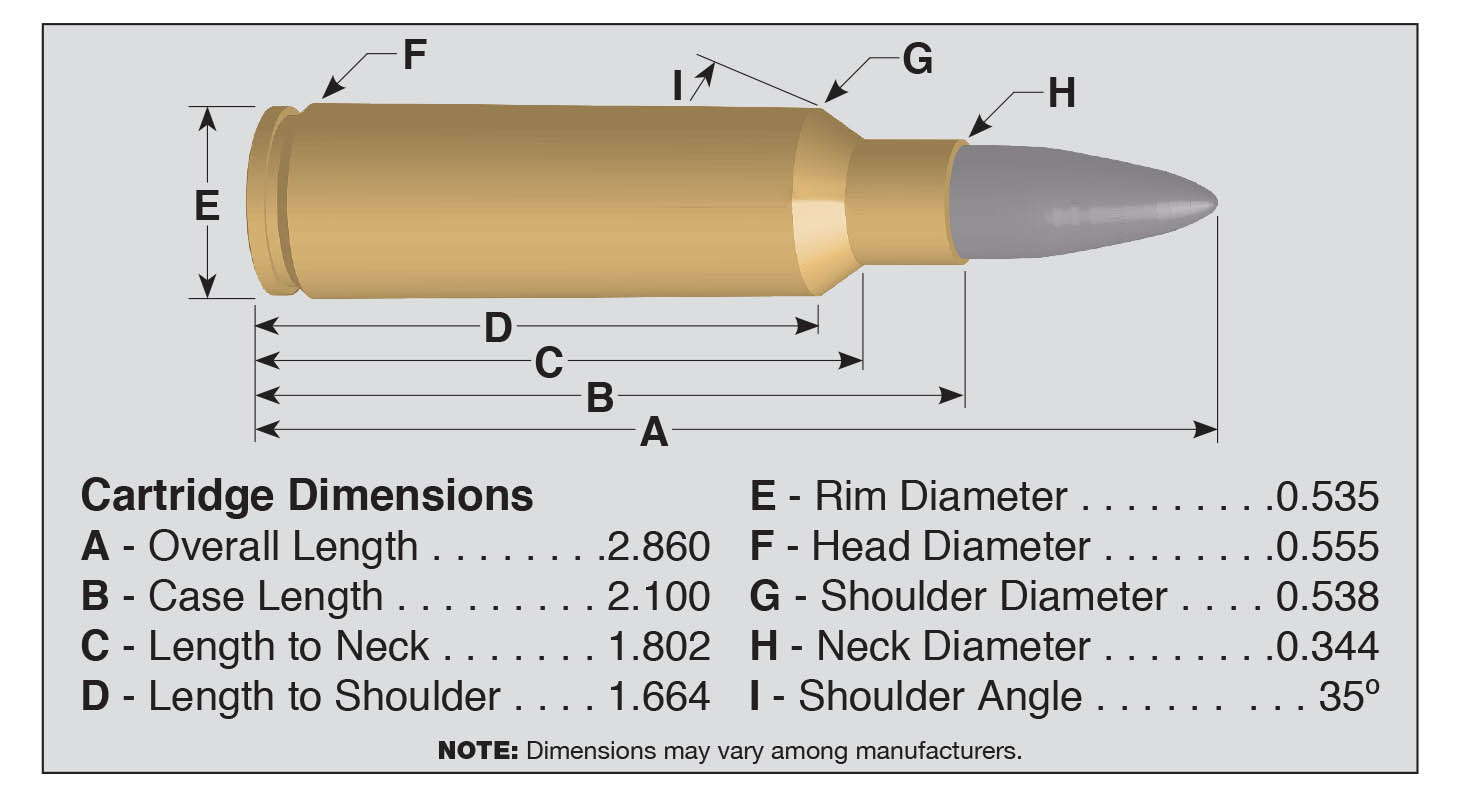

Given the foregoing facts, it was rather interesting to see the announcement of a new cartridge called the .300 Winchester Short Magnum (WSM) early in 2001. Gone was the useless belt. In its place appeared a new rebated-rim case having a base (head) diameter of .555 inch and rim of roughly .535 inch, the latter figure being roughly the rim and belt diameter of the old H&H case. The much larger body diameter was carried forward instead of stopping at a belt. Case capacity increased greatly per unit of length over the old magnum.

Case length is where we see another surprise. It is 2.1 inches, or just slightly more than the .308 Winchester. Capacity, however, is almost equal to the .300 Winchester Magnum, depending upon bullet weight and seating depth. Shoulder angle is 35 degrees. The new round looked noticeably different than anything else – even wildcats. Marketing teams were ecstatic.

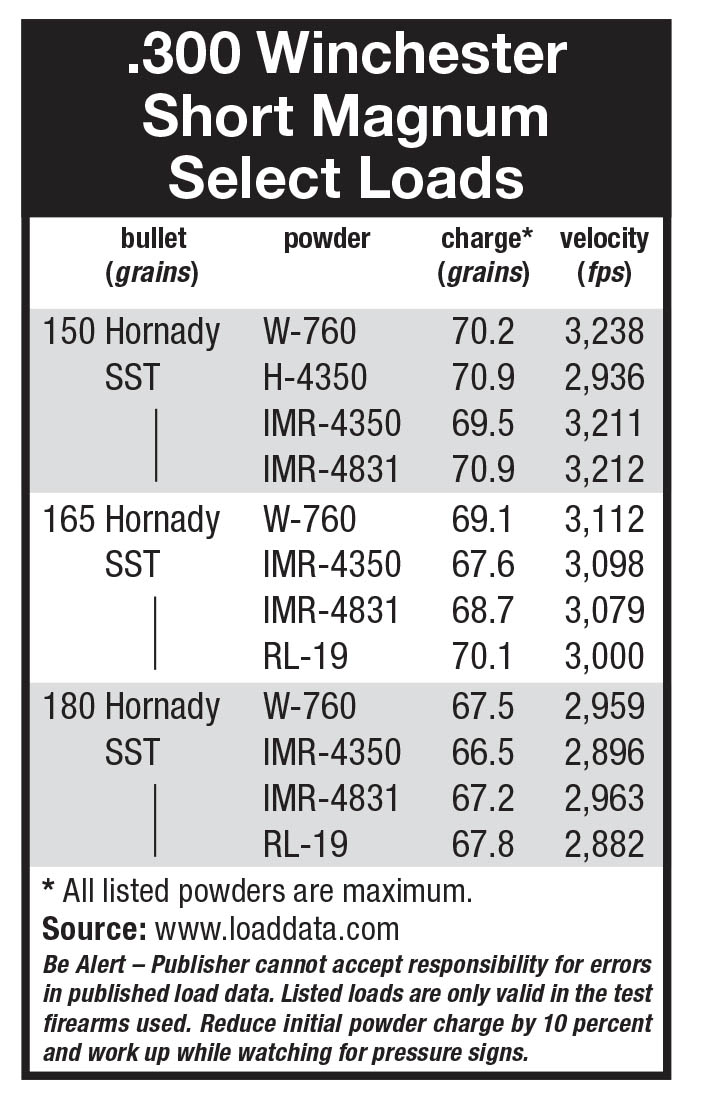

Of course, Winchester produced a shorter Model 70 action to accommodate the new cartridge. The complete rifle was listed with a 24-inch barrel and a weight of 4 to 8 ounces less than the .300 Winchester Magnum with a 26-inch tube. The first year of ammunition production showed a 150-grain Ballistic Silvertip at 3,300 fps, a 180-grain Fail Safe at 2,970 fps and a 180-grain Power Point at the same muzzle velocity. All were equal to .300 Winchester Magnum velocities. Indications are that factory ammunition achieves figures slightly less than this, but then shooters’ chronograph screens are set 10 feet or so ahead of the muzzle while the factory corrects its readings to muzzle velocity. Since the .300 Winchester Magnum’s 3,500+ foot-pounds of muzzle energy is, with proper bullets, adequate for any game in North America, the same can be said for the identical figures produced by the .300 WSM. And, yes, to be absolutely correct, the longer barrel of most .300 Winchester Magnums, combined with its very slightly greater case capacity, means careful handloaders will always see to it the .300 WSM comes in second to their round.

Nevertheless, the .300 WSM is, for all practical purposes, a short .300 Winchester Magnum. After all, once the base of the bullet

rifle firing it. In that light, if a .300 WSM weighs the same as a .300 Winchester Magnum, it will produce the same recoil. Also, given the burning rate of the powders necessary for the .300 WSM, any shortening of the barrel would only increase an already devastating muzzle blast and push velocities down toward .30-06 levels.

There are really only two probable pluses for the .300 WSM. One is more uniform velocities due to the short, fat case, though this is largely negated by years of load development lavished on the .300 Winchester Magnum by competition shooters and the military. Second is that a slightly shorter bolt action with a shorter bolt throw is used for the .300 WSM. For those who feel this is important, there is now that option.

The .300 WSM seems to be a success. Last year, Winchester listed 10 factory loads for the .300 Winchester Magnum, and 11 for the .300 WSM. All totaled there are some 37 by at least seven different makers in the .300 WSM column. On the other hand, just think what a big-game and target cartridge we could have had if the .300 Winchester Magnum had originally been designed on a 2.4-inch .300 WSM case!