The .38 Caliber

Loads for Classic Revolver Cartridges

feature By: Mike Venturino | August, 17

Most American .38 cartridges can be traced to Colt’s Belt Pistol, a .36-caliber percussion revolver that collectors commonly call the Model 1851 Navy. How did .36 get translated to .38? In those days, firearms manufacturers were fond of designating caliber by a barrel’s land diameter instead of its groove diameter. Nominal groove diameter for a .36 “Navy” was .375 inch.

For this system to work in .36-caliber percussion revolver barrels, a bullet’s full diameter needed to be at, or in excess of, .375 inch. According to U.S. Cartridges and Their Handguns 1795-1975 (1977) by Charles R. Suydam, original rounds of .38 Colt heel-base factory loads carried bullets from .378 inch to .381 inch in diameter. Hence the .38 moniker; to put things simply, when a .36-caliber cap-and-ball revolver was converted, it then became a .38 cartridge revolver.

So designers fell back on the 1840’s concept of Minié balls, wherein a soft lead projectile had a deep, hollow base. Upon explosion of the black powder, its thin walls were blown out, gripping rifling and spinning. In order to fit inside .38 Colt cartridge cases, bullet diameter had to be reduced to about .357 inch, give or take a thousandth or two. To modern shooters focusing on handgun precision, it might seem fantastic to expect any sort of performance from a bullet expanding .018 inch before engaging the rifling. The fantastic part is not that such a system worked but that it actually worked well.

Evidence of the .38 Colt’s popularity is that the Colt factory began chambering SAAs for it as early as 1886, and a .375-inch groove diameter was still used. It was dropped as a caliber option in 1914 then resurrected in 1922. Get this: Upon its comeback, barrel dimensions were reduced to be more compatible with Smith & Wesson’s 1899 .38 Special. In fact, Colt .38 barrels were made a bit tight. I have a Colt factory specification sheet dated 1922, and the barrel groove diameter for all its .38s was .353/.354 inch (minimum/maximum). These sizes carried on through Colt’s decades of .38 Special revolver manufacturing and into .357 Magnum Pythons, Troopers and SAAs. For example, my 1969 .357 Magnum SAA’s barrel slugs .354 inch.

During this same time frame, Smith & Wesson was not quiescent in regard to .38 handguns. The company introduced a new round in 1876, the .38 S&W. It was first chambered in a small, top-break revolver that gained the nickname “Baby Russian.” Instead of performing tricks, like having oversized barrels combined with heel-base or hollowbase bullets, the firm designed the new round to take .360-inch bullets with their full diameter extended inside cartridge cases. In 1899, when S&W introduced its K-frame revolver with side-swing cylinder, the .38 S&W was a chambering option, as was its .38 S&W Special cartridge. Bullet diameter with the new round was, for some reason, decreased by .003 inch. The .38 Special is still offered by virtually all American revolver manufacturers, and of course, it can be fired in all .357 Magnum revolvers.

So far we have been concerned with bullet diameters in the many so-called .38s, but let’s look at case lengths. The .38 Colt

Smith & Wesson’s first .38 used .76-inch cases, with the company’s second .38 lengthened considerably to 1.16 inches. Case heads for all these .38s were similar, if not identical – in a practical sense, meaning handloaders can use the same shellholders for all. If any .38-caliber centerfire handgun cartridge was ever made for use with anything other than small pistol primers, I’ve never encountered a sample. (Some .357 Magnum brass was made for large pistol primers.) Also, all can be fired in .38 Special or .357 Magnum revolvers, except for the .38 S&W, which should not chamber due to the cartridge’s large diameter and .360-inch bullets.

Not to be outdone by Smith & Wesson, around 1905 Colt got a few ammunition companies to make a round called the .38 Colt New Police. It was simply the .38 S&W in all respects, except its bullets were flatnose. At about the same time, Colt did the same thing with the .38 Special, calling it the .38 Colt Special – again the only difference in factory loads being a flatnose on the 158-grain bullet. Suydam wrote that the last catalog mention of a “.38 flat point Colt Special” load was by Remington in 1955.

Perhaps now is the best time to mention Britain’s 380/200 Revolver Mk I (aka .38/200) cartridge adopted in the 1920s for the No. 2 Enfield revolver. The revolvers are delightful little double actions, but the cartridge, as copied by the Brits, was simply the .38 S&W of the Super Police variety with a 200-grain bullet fired at a velocity of about 650 fps. Early in World War II, the Germans complained about the Brits using lead bullets, so their military loading was changed to a 172-grain FMJ at about the same velocity.

Depending on the exact load, revolver barrel length and barrel/cylinder gap, velocities of all these black-powder .38s ran from about 650 fps for the shorter ones, to a maximum of 850 fps with .38 Specials. I quote those figures with some firmness, having indulged in handloading all with black powder, except the .38 S&W.

Moving to .38 Colt handguns made in the smokeless-powder era but still with grossly oversized bore dimensions, the best handloading route with modern powders is hollowbase bullets. Sources for hollowbase bullet moulds are nearly dried up. I still have a 150-grain mould from the now defunct Rapine Mould Company, but an even easier route for .38 Long Colt reloading is hollowbase .357-inch swaged wadcutters by Speer, Hornady and perhaps other makers. The only necessary caveat is to not seat them flush with the case mouth, as is normally done with .38 Special cases. Doing so decreases case volume and raises pressures. If the look of a wadcutter bullet sticking out of a .38 Long Colt case disturbs traditionalists, Buffalo Arms is a source of cast hollowpoint roundnose bullets of alloy soft enough to expand as needed.

Let’s look at .38 S&W at this point. If any of the major bullet mould manufacturers produce a design that falls from the blocks at .360 or slightly larger, I’m not aware of it, and it’s not required. A soft alloy bullet will expand to take up a few thousandths of an inch. If the idea is to duplicate Britain’s .38/200-grain military load, Lyman’s mould 358430 is actually intended as a handloader’s equivalent to the factory Super Police 200-grain roundnose. Lyman’s catalog weight for this bullet with its harder No. 2 alloy formula is 195 grains. My 1:20 tin-to-lead blend brings them in right at 200 grains. Shooters preferring to duplicate more modern .38 S&W ballistics would be well served with RCBS “cowboy” 38-140-CM roundnose flatpoint bullets. Naturally, bullet casters have a plethora of options to choose from, along with alloy mixes.

Moving on to .38 Special, it is impossible to come up with something that hasn’t been said many times over in the past 118 years. There are scores of bullet designs available commercially and for the home caster. My favorites run from 150 to 160 grains, and when perusing custom cast bullets in my storage shed, there are shapes from wadcutters to roundnoses to roundnose/flatpoints.

For .38 handloaders, stick with the fastest-burning powders available: Bullseye, Titegroup, W-231 (HP-38), Nitro 100, etc. Except

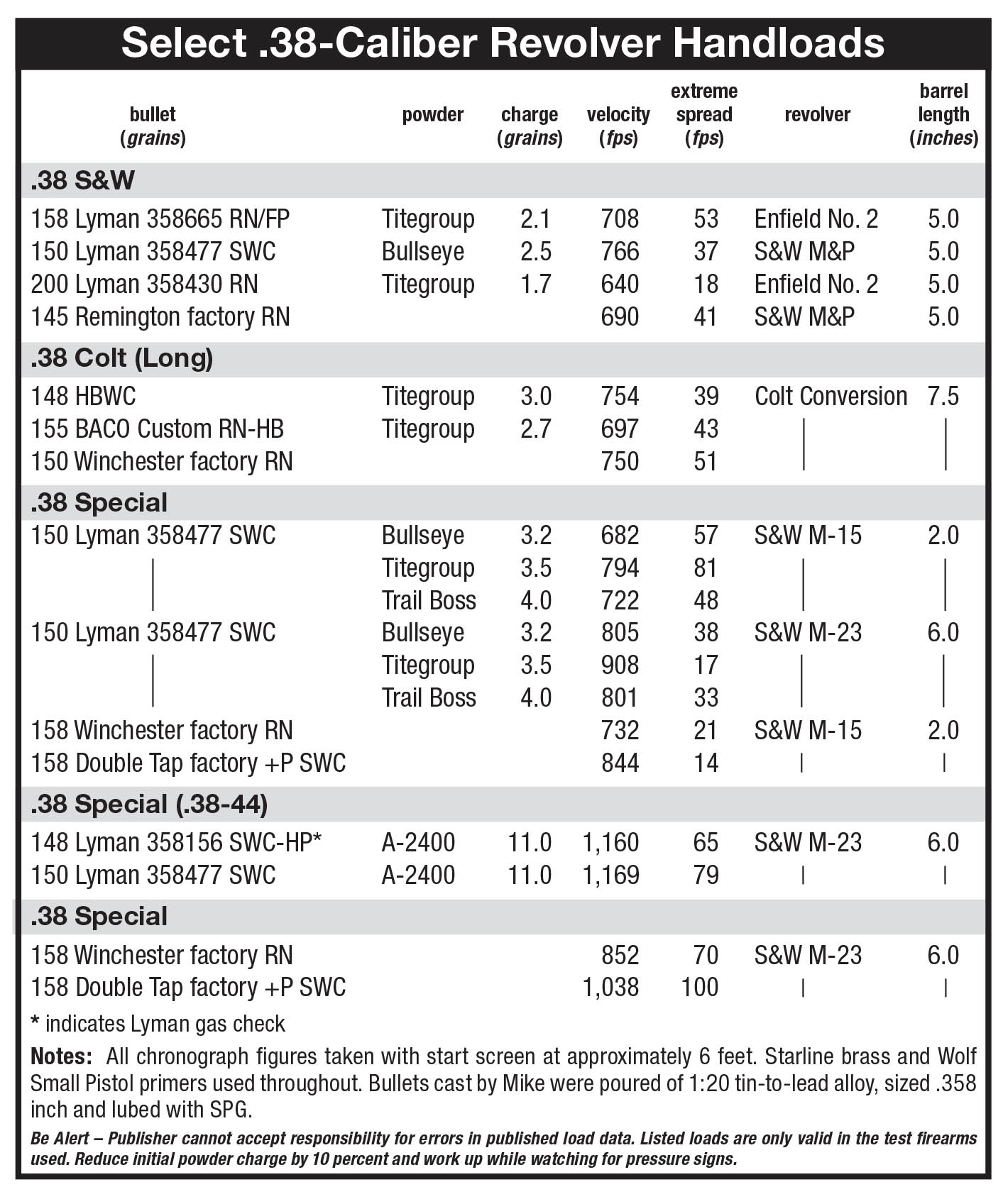

Since black powder loading for Old West handgun cartridges is covered in depth in my book, Shooting Sixguns of the Old West, the accompanying table only shows chronograph results with smokeless propellants. My efforts were to only duplicate published factory ballistics.

Finally, there is a specialized .38 Special handload also requiring special revolvers (pun intended) acceptable for .38-44 factory loads that arrived in 1930. That designation actually meant: for .38 Special revolvers based on .44 frames. Interestingly enough, none of those revolvers were caliber stamped “.38-44.” All were still just labeled “.38 Special.” These were the precursors to .357 Magnums and pushed 158-grain bullets 1,200 fps. The specific handguns meant for this use were Smith & Wesson’s Heavy Duty (later, Model 20) and Outdoorsman (later, Model 23) and Colt’s SAA and New Service. A load that duplicates .38-44s is 11.0 grains of Alliant 2400 with 150-to 158-grain SWC, RN or RNFP bullets.

Like most shooters of Old West handguns, the big .44s and .45s have captivated me most, but the .38s should not be overlooked. They have been some of the most historical American revolver cartridges.