Wildcat Cartridges

.277 Wolverine

column By: Richard Mann | August, 17

Not all that long ago, there was a wildcat cartridge revolution for the bolt-action rifle. Shooters and hunters were looking for that little bit of edge they could get by slightly altering a then-current cartridge case or by designing a new one altogether. It wasn’t long until just about everything that could be done – and that made sense – had been done. The result is bolt-action rifle fans have a passel of cartridges to choose from to fit almost any application that can be dreamed up. Shooters wildcatting cartridges for the AR-15 are feeding that same desire – to have the rifle they like, in a caliber they like, that delivers a level of performance they want.

At the same time, every wildcatter secretly hopes his cartridge will one day become a SAAMI-approved, commercially loaded cartridge. On rare occasions this happens, but what is even more rare is the original wildcatter making any money from his handiwork.

Mark Kexel, president and CEO of Mad Dog Weapon Systems, wanted a cartridge that combined the attributes of the 5.56 NATO, 6.8 SPC, 7.62x39mm and .300 Blackout, but at the same time dismissed the deficiencies of all four when fired from the AR-15. After brainstorming, production of the .277 Wolverine began in 2014.

A .277 Wolverine rifle uses standard 5.56 NATO rifle parts except for the barrel. It pushes a 6.8mm (.277-caliber) projectile close to the velocities of the 6.8 SPC, and it can fire subsonic bullets almost as heavy as those used for the .300 AAC Blackout. Mark believes the Wolverine gives the best of all worlds: more energy than the 5.56 NATO with better trajectory and energy than the .300 BLK.

Mad Dog Weapon Systems provided me with a complete upper receiver fitted with a 16-inch, melonite-treated barrel with a 1:11 twist and a midlength gas system. Also supplied was an assortment of Lake City brass in various stages of preparation and a collection of handload data long enough to make your head swim.

I decided to keep the test simple and use two powders that seemed to perform well based on the data provided, but first I had to make the cases. The first step is to take .223 Remington/5.56 NATO brass and cut the cases off right at the junction of the shoulder and the neck. If making more than a handful of cases, a chop saw is the only way to go. The next step is to run the brass through the .277 Wolverine sizing die. (Hornady makes this die on a custom order basis.) Once sized and once the primer pockets are swaged – necessary with Lake City brass – all that’s left to do is load and shoot.

I remarked to Mark Kexel that this process was a pain, and I might have hurt his feelings a bit. (By the way, wildcatters are notoriously thin-skinned. I know, because I belong to that group.) When compared to something as simple as my “2Fity-Hillbilly” (aka .257 Wildcat or .257 Creedmoor) described in this column in Hand-loader No. 307, making .277 Wolverine brass is rather involved. Yet with a chop saw and an evening to waste, at least it’s not complicated, and when there are 100 shiny, new cases begging for powder, you feel like you have really accomplished something.

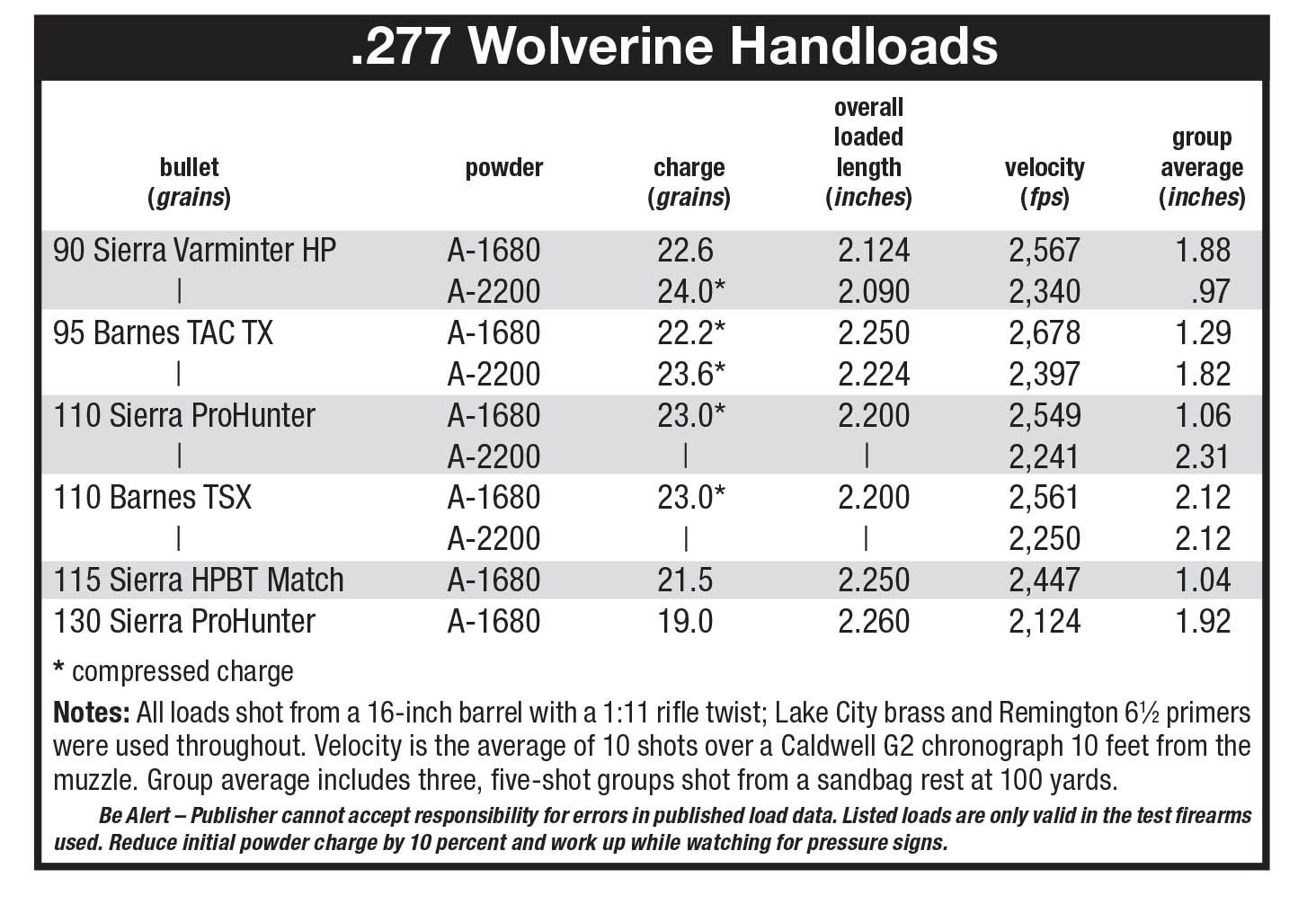

After sawing the cases and passing them through the Wolverine sizing die, I trimmed them to a length of 1.53 inches using Hornady’s Lock-N-Load Power Case Prep Center, a neat little bench-mounted tool that makes mass trimming a breeze. Next, I used the same tool to chamfer case mouths inside and out then swaged the primer pockets with an RCBS tool. Four bullets ranging from 90 to 110 grains were selected and loaded with Accurate’s A-1680 and A-2200 powders. Afterward, given how well A-1680 performed, 115- and 130-grain bullets were selected and two more loads were put together.

In total, 30, five-shot groups, consisting of 10 different loads using six different bullets were fired. The average group size for all 30 groups was 1.65 inches. This included one load that averaged less than an inch and three averaging more than 2.0 inches. I did not “work up” loads by fine-tuning powder charges or overall cartridge length; I just assembled some loads and shot some paper. This left me reasonably impressed with the cartridge’s capability for accuracy, but how does it stack up ballistically?

As with many cartridges, midweight bullets tend to be the most efficient when it comes to ballistic performance, in my experience, and it was no different with the .277 Wolverine. The Barnes 110-grain TSX had a muzzle energy of 1,601 foot-pounds (ft-lbs), and at 300 yards this energy falls to an estimated 807 ft-lbs. With a 100-yard zero and a sight height of 1.5 inches, bullet drop at 300 yards equates to about 18.5 inches. With the 6.8 SPC, you might get another 100 fps in velocity. This would push muzzle energy to about 1,729 ft-lbs, with a resulting energy at 300 yards of 882 ft-lbs. The 6.8 SPC load would also drop around 1.5 inches less at 300 yards.

That’s an advantage, but one hardly worth mentioning, especially considering that when converting an AR from .223 Remington to 6.8 SPC, you will need a new barrel, bolt and magazines. The .277 Wolverine uses the same bolt and magazines as the .223 Remington. From a hunting standpoint, this leaves the most important question as to whether a 110-grain TSX bullet at about 2,550 fps is any better than, say, a 62-grain, .224- caliber TSX bullet fired from a .223 Remington at about 3,100 fps.

The .277 Wolverine is basically a 6.8 SPC in a smaller, more AR-friendly package. I maintain that given the chop-saw step, the cases, while not a challenge, are a pain to make. On the other hand, .223 Remington brass is again plentiful, and this is the case the AR-15 and its magazines were designed to work with. I would also add that if opting for a fast 1:7 rifling twist, you can also enjoy the quietness of suppressed fire. Ammunition hobbyists and AR-15 afficionados will relish in the making, loading and shooting of the .277 Wolverine.