P.O. Ackley's Big .450

Still Good After All These Years

feature By: Terry Wieland | August, 17

Needless to say, I did not take Jack Carter’s advice. Instead, I came home, surveyed my meager inventory of rifles and actions, and chose a rather poorly customized .375 H&H on an FN Supreme action as the starting point. I delivered it to a veteran German gunmaker named Siegfried Trillus with instructions to turn it into a .450 Ackley.

Siegfried removed the barrel and stock and threw them away. He replaced the FN shroud and trigger safety with a new shroud and Model 70-style wing safety, then installed a 22-inch Douglas barrel. He carved a stock out of American black walnut from a tree he had cut down, sawn into blanks and seasoned. Claw mounts were ordered from Germany and a 26mm Swarovski Habicht Nova 1.5x20 scope was installed. With a few odds and ends to come, I had my longed-for .450 Ackley. Little did I know what travails lay ahead.

The .450 Ackley Magnum (not Improved) was developed by Parker Ackley in the 1950s, during the heyday of converting Enfield P-17s to cartridges for elephant and Cape buffalo. The Ackley was not alone. There was also the .450 Watts that enjoyed brief fame, because Jack O’Connor took one on an early safari, and a couple of others. The Ackley gained exposure, however, through P.O. Ackley’s 1960 Handbook for Shooters & Reloaders, and it came to stay. Like most of its brethren, it was based on the .375 H&H case necked up and blown out, so it would also fit in the Winchester Model 70.

The introduction of the .458 Winchester in 1956 cut the ground out from under most of the wildcat .450s, but problems with the factory cartridge soon manifested themselves. This ultimately resulted in Jack Lott developing his own .458 in 1971 – merely the .458 Winchester lengthened by .3 inch, which solved the problems. Most of the serious hunters who owned an Ackley, Watts or other wildcat .450, already having loading dies, and with brass easy to make, stuck with what they had. Jack Carter was among them.

Although articles have been written arguing that one of these wildcats is better than another, in this way or that, the harsh truth is they were all very similar: belted cases for reliable headspacing and tossing a 500-grain bullet at between 2,150 and 2,400 feet per second (fps), depending on how adventurous you were or how much you liked being belted around.

Most were the full-length 2.85-inch .375 H&H case. The Ackley was a little different in that the case was blown out to give it the most miniscule of shoulders – utterly pointless as a shoulder, and any resulting increase in case capacity is imaginary. It does have the one advantage of giving the case a definite neck, and this allows for more consistent grip tension on the bullet. It also reduces wear and tear on case mouths, which is important when fashioning your own brass.

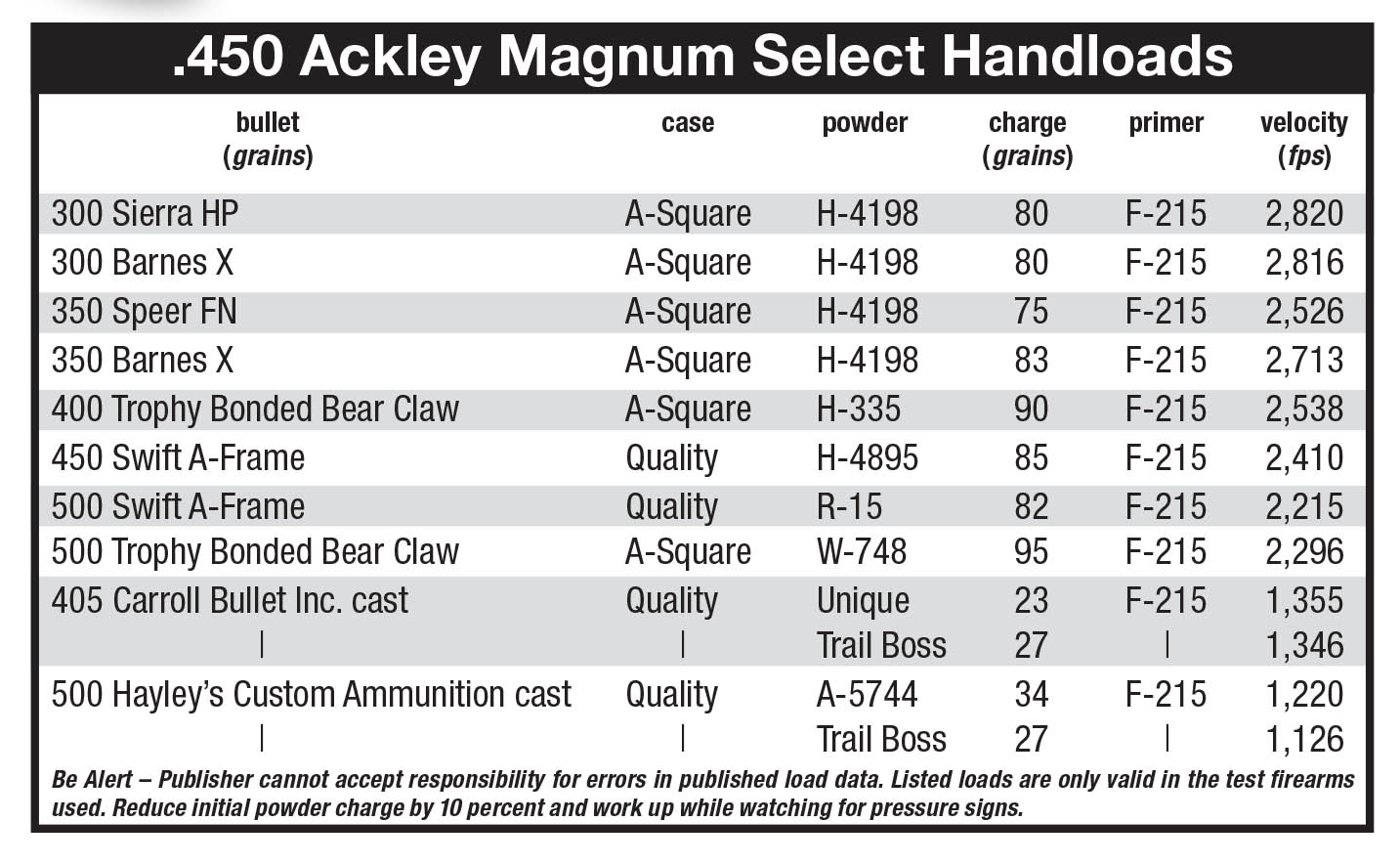

For years, it has been an article of faith that these cartridges should reach 2,400 fps with a 500-grain bullet. When starting off with this cartridge, I used Carter’s favorite load, which was a compressed charge of W-748. At the time, it was about the only powder that would deliver the goods.

It took a number of bulged cases, creeping bullets and wear and tear on my shoulder before I concluded that this is a losing game. In reality, 2,250 to 2,350 fps is just as good – whatever is most comfortable and accurate for the hunter, the rifle and for the cases themselves.

In a cartridge of this power, you need to properly crimp every bullet. This is partly due to recoil and partly the constant pressure against the base of the bullet if the powder charge is compressed. Like most things in handloading, a domino effect can be set off. If a bullet is not solidly crimped, the combination of recoil and powder compression will cause the bullet to creep, which can create feeding and seating problems in the chamber. These you most definitely do not want with a Cape buffalo bearing down. Cases of slightly different lengths – even a few hundredths of an inch – can place the crimp incorrectly or cause case bulging by crimping outside the bullet’s cannelure. Even a slight bulge, so slight you can’t see it and barely feel it with your fingertips, can prevent a cartridge seating in the chamber.

One of the problems with the .458 Winchester, early in its life, was the severe powder compression needed to even approach advertised ballistics. This caused the powder to cake and resist ignition. At one point, I decided to deactivate some loaded .450 Ackley loads, pulled the bullets, then had to use a dental pick to remove the powder that had caked like cement. Since then, I have used mainly extruded powders, and preferably docile ones such as H-4198.

This gives some idea of the problems that can be encountered (or created) by mindlessly pursuing a questionable goal, such as

Bullet weight is another consideration. The standard for a big .450 is 500 grains. It is the Hammer of Thor. Some advocate 400 grains, because of increased velocity, and truth to tell, you can easily get velocity exceeding the .416 Rigby by dropping bullet weight to 400 grains. Personally, for anything requiring a .450, I want 500-grain bullets.

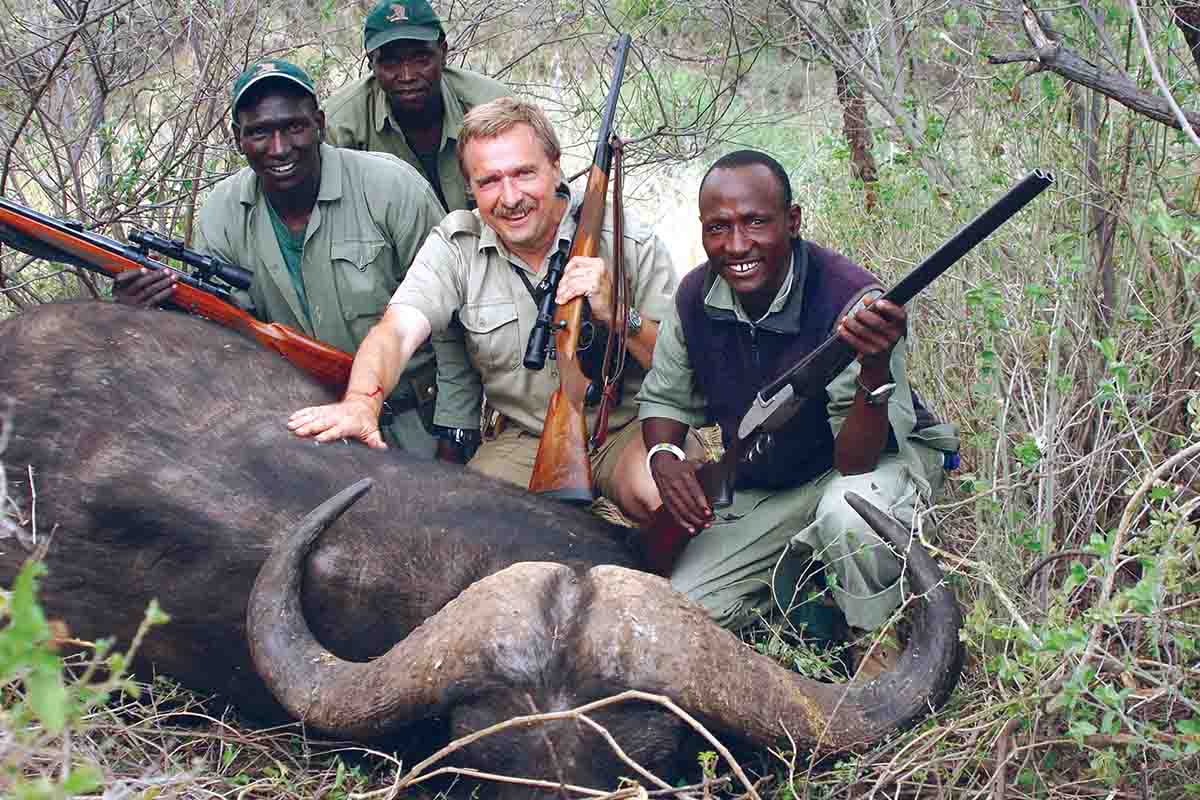

One of the great advantages of all the .450s, however, is their versatility. I have loaded and hunted with bullets ranging in weight from 300 to 500 grains. At one point, I took my .450 Ackley to Africa and left it for two years, with a supply of ammunition of different types, intending to have a rifle ready and waiting whenever I went back. During that time, I used the .450 exclusively, hunting everything from greater kudu, gemsbok and zebra to Cape buffalo, and even carried it one time while tracking a leopard. If reduced to just this one rifle for all the hunting I will do in the future, I would not feel too badly.

It should be noted that, in a pinch, .458 Winchester or .458 Lott ammunition can be used in a .450 Ackley rifle. Obviously, the reverse is not true. However, should your ammunition get separated from the rifle en route to Deepest Darkest, either of the above cartridges is available, you’re back in business. Lott ammunition works best, while .458 Winchester tends to lose velocity because of the roomy chamber, which is something most factory .458 ammunition can’t afford. Neither is ideal, but it beats being unarmed.

This year, with a possible Cape buffalo in the offing, I decided it was time to go through all my brass, use up old handloads and start fresh. I found that I had such a hodgepodge of brass, it was long overdue to relegate it to “practice only” and acquire a lifetime supply of good stuff. Quality Cartridge, in Maryland, offers excellent .450 Ackley brass. It has the right headstamp (important for border crossings), is the exact length and removes all the concerns about crimping in the wrong place, case bulging and the assorted ammunition headaches that have accompanied the Ackley since I got it.

Although the .450 Ackley is capable of some very impressive ballistics, in my experience, the best all-around load is found somewhere just below the point where velocity jumps and recoil jumps geometrically. If recoil could be charted on a graph, it would look like a reversed L, climbing gradually as velocities increase until, at a certain point, it suddenly jumps, with or without any commensurate increase in velocity. With my .450 Ackley, using 500-grain buffalo slammers, this point is just below 2,300 fps.

A final word about the overall configuration of a .450 Ackley rifle, like my FN. Because of its physical size, it does not require a magnum action, and a rifle can be made that handles with the ease of a fine bird gun. This is no small matter with dangerous game. It’s important that it handle easily, quickly and instinctively with reasonable accuracy. The .450 Ackley accomplishes these things, combined with the power to down anything on earth, under almost any conditions. It is really too bad no one ever made it a factory round.