Loading Oddball Rifle Cartridges

Time-Saving Tips and Techniques

feature By: John Barsness | August, 17

Over the decades, I’ve hand-loaded for a number of rifles chambered for cartridges most Americans would consider oddballs, including the .22 Savage High Power, 6.5x54 Mannlicher- Schönauer, 6.5x57R Mauser, .303 Savage, .33 WCF, 9.3x72R and .450/.400 Nitro Express 3-inch. I just checked the website of Graf & Sons (www.grafs.com), a well-known retailer of reloading supplies, and it listed all but the 6.5x57R in stock. I then checked Huntington Die Specialties, (www .huntingtons.com), another top source for oddball cases, which listed RWS 6.5x57R cases for a reasonable price.

Just a few years ago, most oddball cases were often almost impossible to find, the reason many shooters converted brass from other cartridges, but this started to change around 2000, and relatively quickly. In fact, many previously difficult-to-feed rifles suddenly had a surfeit of ammunition and components. In 1990, cases for the 9.3x62 Mauser were difficult to find in the U.S., and the only easily available bullet was the Speer 270-grain Hot-Cor. By the time I bought my first 9.3x62 in 2002, both brass and a wide variety of bullets were everywhere.

A couple of years after that, I bought a nice takedown Savage 99 .303 Savage. Winchester had been the last major manufacturer of ammunition and brass, and I managed to find two boxes of Winchester ammunition at a gun show but wanted more than 40 cases. After consulting books on case conversions, I eventually made serviceable .303 cases from .30-40 Krag brass. It took an hour to convert 2 or 3 cases, so I was relieved a few months later when Huntington started offering new .303 Savage brass from Bertram and Norma.

Some companies offer oddball brass converted from other cases for sale, but if the process involves cutting a new extractor groove, I’d be leery. Several years ago, I wrote a couple of articles on a 6mm Lee Navy Sporter, which included handloads made with Winchester .220 Swift brass. The Swift is the 6mm Lee Navy case with a slightly shorter neck and slightly wider rim, and the loads were based on some found in every edition of Cartridges of the World.

A few months later somebody contacted me, saying another handloader had used my article’s information and blown up his Lee Navy military rifle. I tracked the story down and discovered the rifle’s owner hadn’t used .220 Swift cases. Instead, he ordered cases converted from .30-40 Krag brass that has the same body diameter as the 6mm Lee Navy, but the conversion involved using a lathe to turn rimmed .30-40s into “rimless” Lee Navy brass, including cutting an extractor groove in the case heads.

T

After obtaining good cases, the second problem is dies. Oddly enough, many are easily purchased for modest prices. Graf & Sons, for instance, lists Lee Precision .303 Savage dies for under $30. Dies for most other oddballs I’ve owned are available from around $50 to $100, or they can be special ordered for somewhat more. Oddball rifles often come with dies, because selling the rifle

is a lot easier if the dies are included. There weren’t any dies included with my 6mm Lee Navy, and apparently they’re only available as special orders. Instead, I decided to try the RCBS .243 Winchester dies already on my loading room shelf. The case body of the .220 Swift/6mm Lee Navy case is smaller in diameter than the .243, though a little longer.

A few 7⁄8-inch steel washers are kept on hand to use as spacers under standard loading dies for just such instances. A washer placed under each of the .243 Winchester dies in my Redding T7 turret press turned them into neck-size and seating dies for the Swift brass. Pressures are so low, I haven’t needed to full-length size the brass even after several firings. If they ever become hard to chamber, it would be cheaper to run them into a .220 Swift full-length die, then neck them up again, rather than buy custom Lee Navy dies. (Incidentally, the common belief that the 6mm Lee Navy used bullets of an oddball diameter is not true. Some prototypes did, but the final Navy service cartridge used bullets .243 to .244 inch in diameter.)

Another oddball cartridge I load with substitute dies is the 9.3x72R – or rather the .35x72R. The rifle is a no-name German combination gun with a 16-gauge shotgun barrel under the rifle barrel found at a Montana gun show. The owner said the rifle barrel was chambered for the 9.3x72R, a long, thin, rimmed case that originated as a black-powder round, and included was a box of Sellier & Bellot ammunition, two of which he’d fired. Like many black-powder rounds, the 9.3x72R was eventually loaded with smokeless powder, and the gun had smokeless proof marks.

At home I discovered RCBS makes dies and ordered a set, along with some Norma brass. Unfortunately, none of the 9.3mm bullets commonly available in the U.S. are appropriate for the 9.3x72R, which originally used cast bullets of around 200 grains and, with smokeless powder, very thin-jacketed bullets, like the 193-grain (12.5 gram) flatnoses in the S&B ammunition.

Many German gunsmiths were wildcatters at heart. Since oddball bore diameters aren’t uncommon in older rifles, it’s always a good idea to slug the bores. You might also have such rifles checked out by a gunsmith, but in this instance, the two factory rounds functioned as proof loads: Since the rifle digested them easily, it was obviously in good shape. The RCBS sizing die, however, wouldn’t neck the cases down enough to hold .35-caliber bullets, so I resized the case mouths with a .357 Magnum handgun die – and the .357 seating die also worked.

Obviously, there wasn’t any loading data available for a .35x72R wildcat, so instead I relied on something discovered while researching rifle pressures. Over the years, I’d gotten to know the people at two top piezo-electronic testing laboratories and asked if they’d ever encountered any evidence for the claim that case shape can result in higher velocities through some sort of ballistic magic. The answer from both labs was a very firm no: If two cases of the same caliber have the same amount of powder room, when loaded with the same bullets and powders, they’ll produce essentially the same velocity at the same pressure.

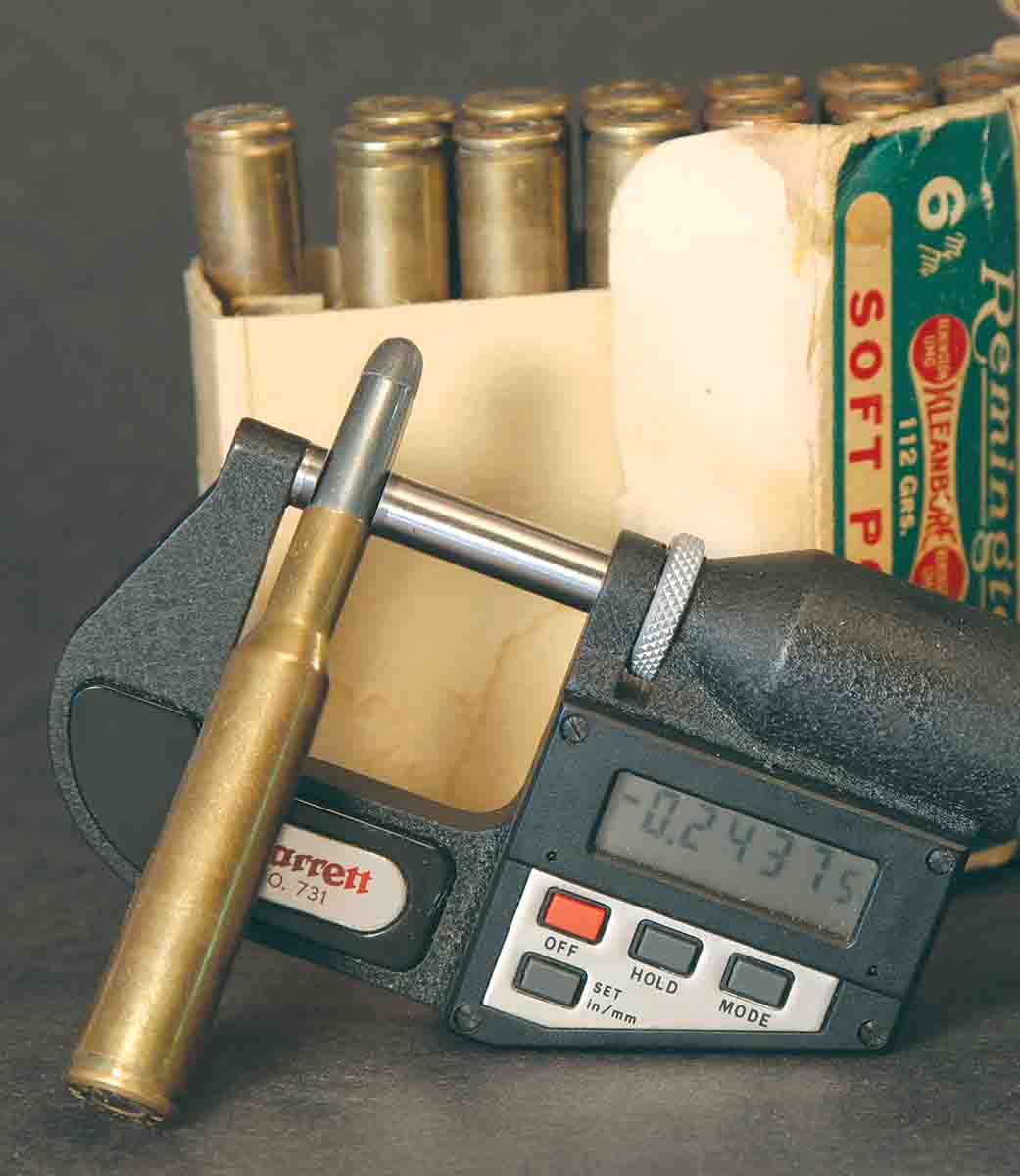

This knowledge has come in handy when loading oddball cartridges, including the .303 Savage. When I acquired my .303, all published loading data was decades old with many powders discontinued. Even if familiar powders were listed, the designation was often simply “4895,” rather than IMR or Hodgdon. So the capacity of a fired Winchester .303 case was compared with a fired Winchester .30-30 case.

Instead of using the common method of filling the entire case with water, however, I hand-seated a .30-30 roundnose to the cannelure, because powder capacity does not include the part filled by a bullet, especially the neck. If it did, the powder capacity of the .30-30 Winchester would be reduced considerably by cutting off half of its long neck. Instead, with a bullet seated to the standard overall factory length of 2.55 inches, the .30-30’s powder capacity is the same at any neck length. Hand-seating a bullet in a fired case squeezes out the meaningless water in the neck, and seating a cannelured bullet to the groove in two cases of the same caliber provides a precise comparison in their capacity.

As it turned out, the two Winchester cases held exactly the same amount of water, right down to .10 grain. Different brands of brass normally vary in weight, changing capacity slightly, but my water test indicated modern .30-30 data could be used to load the .303 Savage, since both rounds were designed for approximately the same pressures. This was confirmed when “.30-30 Winchester” loads resulted in .30-30 velocities in my takedown .303 Savage.

The same basic method also resulted in loading data for a 1950’s Sauer drilling with a 6.5x57R rifle barrel under two 16-gauge barrels. The gun came with several boxes of Hirtenberger factory ammunition loaded with Sierra 120-grain ProHunters (American bullets aren’t uncommon in European ammunition) and a set of RCBS dies. Obviously, the modern Sauer could take more pressure than the old combo gun, but there wasn’t any sense in exceeding the factory ammunition’s chronographed muzzle velocity of 2,800 fps.

I decided to load the Nosler 125-grain Partition, in case I ran into an elk while bird hunting, and found the water capacity of the 6.5x57R was within a grain of fired 6.5x55 Lapua cases. Using mild “Swede” data for older rifles, I worked up a load with 45.0 grains of Hodgdon H-4350 that provided 2,750 fps, and it shot to exactly the same place as the Hirtenberger factory load.

I’ve used both the factory and handloads on several animals (though not any elk yet), but with the Hirtenberger deer ammunition diminishing and H-4350 getting scarce, I also decided to work up a load with Hornady 129-grain Spire Points and IMR-4451. Using the same 6.5x55 data, I worked up to 44.0 grains, which provides 2,700 fps and also shoots to the same point of impact.

Another essential in making oddball ammunition, however, is several sources of information, because not all of it is safe – or correct. My experience with the 6mm Lee Navy is a good example, with plenty of contradictory information in both books and cyberspace. Luckily, I found a copy of Eugene Myszkowski’s fine book, The Winchester-Lee Rifle (1999), painstakingly researched from original military records and the author’s personal experience with a number of rifles. Myszkowski reported that most Lee Navys feed and extract .220 Swift cases without modifying the rim or extractor groove, and so does mine.

Whenever possible, I also try to keep some cartridge cases for rifles no longer owned, because they might be useful someday. I hadn’t owned a .220 Swift for several years when starting to load for the Lee Navy rifle, but having Swift cases on hand simplified life. The same applies to loading dies. Right now I have over 80 sets, but only two-thirds are for firearms presently owned. Several of the others have turned out to be very useful when a rifle chambered for some oddball cartridge follows me home.